There are interesting characters, there are fascinating characters, and then there’s John Foxx.

Born Dennis Leigh in Chorley, Lancashire, Foxx attended art college in Preston in the 1960s, soon winning a scholarship to study at London’s Royal College of Art, where he began experimenting with tape recorders and synthesizers. His first significant band, a glam-rock outfit by the name of Tiger Lily, was beginning to feel wooden and irrelevant in the light of punk’s arrival; having declined an opportunity to join an early incarnation of The Clash, Foxx re-christened Tiger Lily Ultravox!, and the band soon secured a deal with Island Records.

During that their first two years with Island the band released three albums, beginning with a self-titled effort produced with Steve Lillywhite, Brian Eno providing additional assistance. That album, and its follow-up, Ha!-Ha!-Ha!, didn’t achieve a great deal of commercial success but provided vivid snapshops of a band eager to evolve, and bugger the consequences. This surge of activity culminated in 1978’s magnificent Systems of Romance – a more minimalist and electronic album than its predecessors, recorded in Germany with legendary producer Conny Plank. Though a key precursor to the imminent synth-pop explosion, SOR sold well beneath expectations, and Ultravox (who by this point had jettisoned the exclamation mark from their name) were dropped by Island.

After a not unsuccessful tour of the States, Foxx announced his decision to leave the band. Ultravox would go onto achieve massive commercial success with an increasingly insipid pop sound (and the recruitment of one Midge Ure), but it was Foxx, now unchained and entirely self-reliant, who flourished creatively – releasing arguably the first and certainly most perfectly realised “pure” synth-pop record of the 1980s, Metamatic. Though acclaimed the time, hindsight has shown Metamatic to be far more than simply “a good album” – it’s among the most important and influential art-works of the 20th century, and tellingly one of only a handful of records that Aphex Twin has publicly expressed his admiration for.

After the stark, metallic Metamatic, Foxx explored more bucolic territory on its follow-up, The Garden, and he founded a studio of the same name in Shoreditch the following year. There he produced demos for Virginia Astley’ sublime arcadian oddity From Gardens Where We Feel Secure and hosted sessions for the likes of Depeche Mode, Brian Eno, The Cure, Nick Cave and Siouxsie & The Banshees. He collaborated with Anne Clark on Pressure Points, and provided music for Antonioni’s Identificazione di una Donna, but his own original solo work was beginning to lose direction and lustre – The Golden Section, a conceptual retreat into rockier, more conventionally psychedelic sounds, didn’t quite hang together, and 1985’s In Mysterious Ways was met virtual indifference by the world at large.

At this point most musicians would start re-hashing their earlier, more popular work in a bid for commercial acceptance, but Foxx was always too complex and restless either to rest on his laurels or simply churn out more of the same. In the event of it, he was brave enough to withdraw from the world of pop completely – working as a graphic designer under his birth-name of Dennis Leigh, he spent much of the mid-80s creating covers for a number of high-profile books including Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh and Jeanette Winterson’s Sexing The Cherry. He was lured back to music by the emergence of acid house, the sounds of which he recognised as an update and extension of his own proto-techno confections. He released two records under the name Nation 12, one of them a collaboration with Tim Simenon of Bomb The Bass, and – ever alive to the possibilities of the future – wrote the music for the Bitmap Brothers computer games Speedball 2 and Godz. After taking up a teaching post at Leeds Metropolitan University, Foxx was offered the opportunity to direct the video for LFO’s Warp Records smash ‘LFO’, which he did with some aplomb, cementing the relationship between his own work and the new UK-refracted machine music of Chicago and Detroit.

Since then Foxx has kept busy in a range of media, exhibiting films, photographs and other art-works, and releasing a number of acclaimed collaborative LPs with the likes of Louis Gordan, Jah Wobble and Robin Guthrie. However, his most impressive and resonant post-1990 works are the ambient masterpieces Cathedral Oceans and Translucence + Drift Music (the latter a double-CD collaboration with Harold Budd). These albums aren’t just albums, they’re doorways into different orders of reality, and are nowhere near as well known as they should be. Throughout his career Foxx has been hugely concerned with space, and with the individual’s place in the world. In the Ballardian nightmare vision of Metamatic, that world is one of urban violence and disquiet, but on Cathedral Oceans, Translucence and Drift Music, it’s contemplative, tranquil, completely submerged.

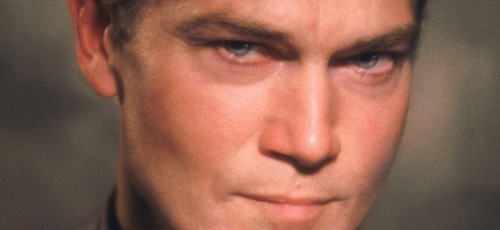

FACT was lucky enough to be able to interview John Foxx face-to-face in London earlier this month. Also present for the conversation was Ben Edwards, AKA Benge; in fact, the conversation took place in Edwards’ Hoxton studio, where he and Foxx are working on a new album under the name John Foxx & The Maths. Some readers might remember Benge’s 2009 solo album Twenty Systems, an “archaeological” but uncommonly soulful tribute to the unique sounds of specific analogue synthesizers, which caught the attention of such luminaries as Brian Eno and Robin Rimbaud, not to mention Foxx himself.

Ben will join Foxx, former Ultravox guitarist Robin Simon and a number of other personnel for a special “analogue show” at London’s Roundhouse on Saturday 5 June, playing new songs from John Foxx & The Maths as well as classics from Metamatic and the Ultravox era, and employing all the Moogs, ARPs and drum machines that Foxx put to such future-rushing use in 1980. Staged by the Short Circuit festival, the evening will also feature DJ sets from (among others) Jori Hulkonnen and Gary Numan; earlier in the day, Mark Fisher will chair a panel discussion event featuring Foxx, visionary author Iain Sinclair and Ghost Box’s Jim Jupp (Belbury Poly) and Julian House (The Focus Group), discussing various themes associated with the fields of psychogeography and hauntology. Tickets for the events can be found here; anyone who cares seriously about electronic music, not to mention great pop, ought to be attending.

As the above overview demonstrates, Foxx has had such an illustrious, various and incident-packed career that even an intensive 3-hour interview such as this one could only scratch the surface. Rather than focussing on the oft-dissected Metamatic and his preceding years in Ultravox, we talked instead about Foxx’s deep-seated love of London, his pioneering ambient recordings, the special character of analogue synthesis, his work during the rave era and the free-spirited studio approach that he learned from Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and Conny Plank.

Ben and John – you’re working on new material together. How did you first encounter each other’s work?

Ben Edwards: “We met for the first time in October, but I’ve known John’s work for years.

John Foxx: “I heard the Twenty Systems record, and that’s how I heard about the studio.

BE: “John had a best of called Glimmer that came out the same week as my Twenty Systems record – we hadn’t met at this point, this was a year and a half ago. I was quite interested in the fact that he was being reviewed in the same issues of magazines that I was, and though I don’t think anyone compared our work, it occurred to me that there were perhaps some similarities in what we were both striving for. Then John got in touch with me…

“We really started working properly together only at the end of last year. Some of the tracks we’re working on are things that John’s had knocking about for a while…”

JF: “One or two of them, yes, and the others are things that we’ve just started spontaneously.”

Have you been sending each other bits and pieces back and forth and working separately at times, or has all it taken place here in the studio?

BE: “It’s all in here. It’s just good fun setting up a sequence on a synth, and jamming along with it, firing up an old drum machine or something.”

JF: “We use this great mic – it looks like nothing, it’s just an old Philips stereo microphone, but it’s perfect.”

BE: “It really suits John’s voice.”

JF: “So we don’t need to do many takes, really.”

BE: “When I normally record people singing, we’ve got a live room across the way, it’s properly set up for it – a soundproof room with headphone links in between. And [John and I] tried using that really early on, but it just didn’t feel right. So we started recording the vocals in here, and we’ve found that it just…works.”

“I don’t think we started off with any idea of what we were going to do at all.”

The new vocal tracks that you’ve played me are quite poppy, rhythmic and forthright – surprisingly so, I would say, given the more reflective, less beat-driven feel of a lot of John’s recent work and also Benge’s Twenty Systems. To what extent did you know what kind of sound you were aiming for, and to what extent did it arise out of the process?

JF: “I don’t think we started off with any idea of what we were going to do at all.”

Was the vocal component pre-conceived, or did that come later as well?

JF: “Well, a lot of the tracks started because of Ben’s arpeggios – he’d set something up on one of the systems and I’d see what would happen when I sang to it or played to it. It’s strange, [the new album] is so rhythmic, I suppose because all the arpeggios are very rhythmic things in themselves: when you sing along, you suddenly feel like you’re singing a song, rather than something more abstract. The melodies just come through the rhythm and the words.

“I just start with titles, ideas of what might be interesting to write about; I have no idea of what the finished song is actually going to be like, or what form it will take. Then Ben will make an arpeggio and I’ll listen and try to find which of the titles it might work with, the build up from there; things accumulate. A lot of it happens quite quickly, a couple of tracks took just a few hours, we just…arrived. I think when things happen like that, it’s difficult to say ‘No, this isn’t what we should be doing…’. But I didn’t expect it to be as song-oriented as it’s turned out to be.”

BE: Nor did I, really. I’ve been doing non-vocal stuff for years, and it’s only in the last two years that I’ve even considered working with vocalists, for some reason I’ve just never had the inclination before. Gradually I have been doing more and more vocal stuff, but I’ve never with anyone that can write and sing their own songs – it’s nice working with someone who comes along to the studio, brings an idea, and develops it into a fully-fledged song, with them singing on it. So from my point of view I’ve really enjoyed working in this much more structured, song-based way, as opposed to just being content to doing lots of abstract stuff.”

What about the rhythms? Maybe it’s just the monitors, but they sound very dancefloor-oriented, very tough.

BE: “I’ve always fought against doing 4/4 bass stuff. I didn’t really come from a dance music background, I’ve always come from a more art-based background. I’ve done ten albums over the years, and I don’t think any of the first four albums had a single 4/4 pattern, they had much weirder time signatures. Maybe I’m just getting to the point now where I just want to say, ‘OK, simple things work. 4/4 works.’ And this project feels like a really good opportunity to get the simplicity of a song out there, with a decent beat, a nice melody, good sounds – it’s really the simplicity of it I like. I’ve given in to it [laughs].”

JF: “It’s the textural stuff that I like about what you [Ben] do, because you just hear one of those arpeggios, and it’s like a piece of architecture already. You’ve got this great abstract pattern there in front of you, and it’s very exciting because it feels solid and real already, and all you have to do is just position things on it, and in it, and away you go. If it were visual, it would be like a big matrix that you could arrange any way you want. That’s what makes it so interesting – it’s very sculptural.”

“You just hear one of those arpeggios, and it’s like a piece of architecture already…”

Have you thought about coming up with any kind of visual realisation of, or response to, this music..?

JF: “We’re both interested in film, and Ben in particular has been collecting old 70s video equipment with a view to making film…”

BE: “It’s just in the same way that I’m interested in ‘lost’ musical equipment – stuff that once represented the very peak of technology, but which has since been superceded, and been deemed redundant as things have moved on. I like to go back and rediscover these amazing machines – like all these synths I’ve collected over the years. I’ve been doing this with video recently, buying all these old pneumatic machines and things like that – I think that’s going to be a reallty interesting area to explore. And going back to the physicality of the music, there’s something about the big, old equipment that you interact with physically, which affects that way that you construct tracks with it.”

But you’re not totally resistant to digital systems and processes?

BE: “I’ve always run analogue and digital systems together. But I have gone through periods of wanting to make stuff that sounds as cutting edge as possible, almost for its own sake, the kind of thing where people are baffled as to how it’s done. Less so recently.”

JF: “I find all these methods interesting. In a sense I don’t mind which I use [analogue or digital], because I’m concerned with songs first and foremost, and stories – that’s what interests me. But some stories depend upon that reference to analogue and older, what Ben calls ‘lost’, equipment, and lost technologies. So where it’s appropriate, that’s very interesting. It’s to do with sensitivies, isn’t it? Because if you have a sensitivity to that kind of reference-point, and you can use it to tell a story, then you’ve suddenly got access to – and can provide access to – another kind of world. A world that people might not have been consciously aware of before, but which they now recognise, because they’ve been unconsciously aware of it all along.

“It’s one of the great things that art can do: provide a perspective that puts people in touch with things that are there in the unconscious but which they’ve not necessarily been aware of previously. I certainly got that feeling of recognition when I listened to Ben’s Twenty Systems. With that record you had a digital reproduction of a very sensitive reaction to older technologies, and I recognised that, and thought that’s very interesting. Inevitably you have to use that digital vehicle now, because there isn’t anything else anymore, the digital has replaced and contained everything else.

“To use analogue now is to recover something which everyone recognises but which has been lost amid the rush of popular technology.”

To use analogue now is to recover something which everyone recognises but which has been lost amid the rush of popular technology. In a coarser way, it’s a bit like rediscovering black and white photography after colour photography came out. Because everyone jettisoned it, thinking that’s old-fashioned now, but then ten years later everyone started looking at old black and white photography and thinking, ‘Gosh, that’s really special, isn’t it? It’s totally different, you can’t do it like this anymore. Where can we buy the old film-stock?’ And that stock tells a story, tells a different story, to the new stuff.

“It’s interesting sometimes to delve back and choose things and see them in the light of new technologies. One of the reasons for the modern recovery of analogue synths is that all the speakers now are a lot better than they were back then [in the 70s and 80s]. When the synths first came out, you couldn’t hear those frequencies, you couldn’t hear the bass or top-end at all, because the speakers just weren’t good enough. And when you hear old recordings now, you think, ‘Wow’ – there’s a lot in there that people just couldn’t hear at the time, but which you can hear now. So there’s a real complexity of texture and sound that those instruments can make, and have always made, but that we were only able to hear once a new wave of technology allowed us to. So you’re constantly reviewing the past through new technology – and there’s this loop that goes on all the time, in all the arts.

How so?

JF: “All media’s like that. Take painting. Painting will have a value again because it’s been replaced in the imagination for a long time by photography, and people have forgotten that these images [paintings] are made by hand, and that there’s a value to hand-made images that you can’t get any other way. People haven’t looked at painting like that yet, but I think they will, very soon. Film’s the same – Super8 has become, or is becoming, more interesting – it came to be thought of as rubbish, despised domestic product until you couldn’t get it any more, and then you can digitise it, and look it on the big-screen, cinema-size, and you can see all the grain and all the imperfections and suddenly it becomes so beautiful – and you can’t do that digitally, no matter how hard you try. But you can scan it, put it through digital technology, and suddenly you can see it properly, just like you can suddenly hear that kind of texture that’s unavailable anywhere other than from analogue synths.

“And they all tell different stories. Super-8’s become a short-hand for memory in media now. If you want to put someone back in time, you use a Super-8 episode – it’s done on TV all the time. And these synths do something similar. But the other thing that’s interesting is that there are things to be done with [analogue synths] that weren’t possible at the time. You can re-arrange them now, and you can mix them with other elements in a way that simply wasn’t possible 20 or 30 years ago.

“It’s terrifying, that digital perfection that you can go for. And of course it’s not perfect: it’s actually quite ugly in that it’s over-perfected, over-clear.”

BE: “We’re recording on to a computer in here, and I have got a tape machine but I’m not going to just use tape as a medium, I’m going to record onto hard disk still, and then put it to tape as an effect and then bring it back onto hard disk. It’s true what John says, we’re using the old equipment but we’re getting this almost pristine version of it, and the working methods are much more simple now – whereas in the past you’d be setting up tape for half the day rather than actually recording or making music.

“If you’re mixing on the computer all the time you can constantly change and go back and fiddle around with it and you can end up never really finishing stuff, but if you’re mixing on analogue you kind of have to commit at the end of each day – and it’s a completely different working mentality. It’s nice having those limitations sometimes, but I suppose we’ve got the best of both worlds.”

JF: “I always think of it as like drawing, gestural drawing, like Degas or someone. Degas used to rehearse; those drawings looks spontaneous, but he used to rehearse for days, and he’d do hundreds of the same drawing, like an actor practising a part, and he’d end with this perfect drawing that had taken him a few days of gaspingly hard work to get to, and throw the earlier attempts away. By that point he could do it with one gesture. And that analogue way of working is a bit like that – you do dozens of takes until you get one that works. But with digital you can keep on doing that forever – you can do hundreds of takes, and chop singles words out and move whole things around, so you’re less committed in a way; if you work in a more analogue way, it forces you to accept some things with faults and then a week later you can walk in and they don’t sound like faults anymore, they’ve become part of the quality of the thing. But if you work digitally you keep on going until you perfect it, and it becomes rather boring. I know people are so involved of the process of mixing that they can mix for weeks, years in fact. And you can never get to the end of it – it’s terrifying, that digital perfection that you can go for. And of course it’s not perfect: it’s actually quite ugly in that it’s over-perfected, over-clear.”

And it moves further away from the idea of recording as documenting a performance…

JF: “Exactly, yeah. It’s all a tight-rope though, because what attracted me to studios in the first place is that you can perfect things in a way, or at least you can discard things you don’t want, which you can’t do live, and then you have a document of it. And that’s the big difference between this kind of music and, for instance, classical music – classical music’s written, and it’s performed as written, and the recordings are performed as written, with only minor variations of speed and emphasis, which for people familiar with the music are very significant but which are hardly noticeable for those who aren’t. Whereas the kind of music I make is much more to do with the impossible – you can’t play it, when you come to perform it live you really have to figure out how you’re going to play it. Because the point is to use the studio for what it does best: making impossible music.

“The point is to use the studio for what it does best: making impossible music.”

“I think we’re at the end of an era of recording now, because people can’t afford to sit in studios anymore, for a year or two. We’ve ended an era we’re people could sit in a studio for a year and use everything in the armoury and make something that they felt was a perfect world – like Pink Floyd with The Dark Side of The Moon, and The Beatles, and people like that – they had the means to sit down and do that, and they made a kind of music that had never been heard before, because that kind of technology wasn’t possible. It’s a bit like Hollywood in the 1930s – it’s gone now, and you’re not going to see those kind of films again, and it’s a defined era. You can maybe pastiche it sometimes, but we’re in a different era – an era of reassessing analogue stuff through digital means, and retrieving or choosing some elements we want from the past. But we’re not trying to recreate the past, we’re just trying to move on into what’s possible of the future, while keeping all the options open as we go along [laughs].

“I think maybe in 30 or 40 years when people look back and reassess this era, they’ll see the complexity of some of those recordings is at least equal to an orchestral piece of music, and in my opinion much more so. Because the actual process of recording is so complex, and so multi-layered – I mean, you start with 24 tracks and you’re working to that, and you go on and on, and layer and composite to a degree that’s just not available to, or possible for, classical musicians.”

And unlike classical music pieces written for orchestra, an album-as-recorded can’t be satisfactorily replicated…

JF: “You couldn’t do it again. It exists in that particular technological and artistic era, and the technology enabled the art. And we’ve gone into a new era now.

“When I started in ’74 or ’75, I would’ve done anything to have a computer – it was exactly what I wanted. But it was impossible, there wasn’t any way of doing those things yourself, you had to use a studio. I think four-tracks and soon after eight-tracks were becoming available, but they cost thousands, an individual just couldn’t afford them. So people had to go that route of using studios, there was no other option, until the 80s and 90s when the technology became small enough for you to be able to work at home. But what you lack in working at home is the interaction with all the other people that are around in a studio. Because that breeds different results. If I work by myself at home, it’s very different to what I come out with when I work here with Ben. I can’t replicate that. Because that human interaction is phenomenally complex and interesting. And when you get two or three or four people involved in it gets exponentially more complex and interesting, if difficult to manage.”

“I think what happened with rave was part of a long history that goes back further than the 80s synth era, right back to psychedelia and beyond that as well. The big ‘rupture’ for me wasn’t rave, then, but the arrival of sampling.”

You’re also working on material with Paul Daley [formerly of Leftfield] at the moment. Can you tell me about that project?

JF: “We may perform one of the pieces at The Roundhouse. It’s not quite finished yet, and Paul’s reluctant to part with anything as yet, but he has said we’ll have one of the mixes to work with for the performance.

“I’m on about half the album, and the other half are instrumentals. I’m the only person who’s got a voice on it. It’s a very club-oriented, very digital, very defined dance music. I like that kind of thing: it’s that understanding of how to optimise speakers, it’s a feat of engineering and judgement, and Paul is just great at that. I just supply the melodic bits and the voice and work out songs, and he discards the ones that don’t fit into that world of his, and uses the ones that do. It’s great to drop in occasionally and listen to the process, because he re-arranges everything constantly. So I’ll sing to one track and play some bits, and I’ll come back a week later and he’s reorganised the whole thing really ruthlessly. It’s great to see that in operation. Sonically he’s fantastic, he’s a real artist, and in a totally different way to the way Ben works.”

You were very quick to embrace the sounds of house and techno come the late 1980s. History likes to portray the dawn of rave as a sudden rupture, which I suppose it was, at least culturally speaking. But did did it feel like a rupture musically, or did you consider it more of a natural evolution of what people like yourself had been doing earlier in the decade?

JF: “It all seemed like one continuity to me; things just taking different forms, that’s all. I think what happened with rave was part of a long history that goes back further than the 80s synth era, right back to psychedelia and beyond that as well. The big ‘rupture’ for me wasn’t rave, then, but the arrival of sampling – I just didn’t feel sampling at all. I watched it run off and chase itself to death; it never interested or nvolved me. I know there’s a real art to it, and of course some of the records I like – we were listening to ‘Rockit’ by Herbie Hancock this morning, and that’s tremendous. But that was about it as far as I’m concerned.

“The era of ‘big production’ in pop music happened just after that, in the mid-80s, and then along came imitation soul, which I just thought was pathetic. Everything seemed so pseudo and ersatz and I just could not involve myself it. And around that time I totally lost direction myself, and got bored, and wandered off and did other things for a while.”

And acid house brought you back to music?

JF: “Sort of, yes. One day I went round to a friend’s house and he played me some of the beginnings of acid, around ’87 or ’88, in Vauxhall it was, and I remember thinking, ‘Wow, this is great’. On just that one track you could hear all the history of synths and dance music coming together again in a slightly different form. So it was a continuity for me – and it solved the problem, which, as I said, was sampling. We were suddenly back to something I felt comfortable with, and then I bumped into Bomb The Bass and became newly immersed in that whole world of small independent labels and underground scenes – that was the kind of world I’d grown up with so I felt at home there, and I joined in again.

“It was interesting because a lot of people that worked in these scenes were people that bought my records when they were kids – Metamatic was one of the first records that Tim [Simenon, of Bomb The Bass] bought, so he wanted me to do some work with him. He wanted to get to grips with synths, because he’d been sampling everything up to that point, so I got the 909 out and all the old equipment. People began to use them quite extensively again over that period. Everything was changing, all the time. Even things like reggae started to get electronic, and you got that electronic dub movement which links up with things that influenced me when I was growing up in Manchester and going to what were called blues nights, West Indian parties where you’d have lots to drink and some goat curry and turn the soundsystem up. At the blues you got that massive bass that you couldn’t hear any other way, at that point at least; there were no other speakers that could deliver that kind of power. So you have all kinds of older technologies and cultures coming into play [in the rave era]. I was already familiar with many of them, but not all.

“A lot of Metamatic is dub. We were trying to get that kind of separation and abstraction between the sounds.”

When people think of the early UK blues nights and reggae soundsystems, people tend to think primarily of London and Bristol, but there was plenty of that in the North as well, wasn’t there?

JF: Oh yeah, there was Ponderosa in Manchester, and even Corporation St in Chorley, where my grandmother lived. At the top end of that was a guy from Jamaica called Mr Hughie who came to Britain to work in factories, and I knew him from when I was four or five years old. My best friend Richard was a Polish immigrant and his family ran a boarding house; the first tenants they got were Mr Ewie and May, his wife. Then Hughie bought a house in Corporation St and used to run blues nights, and I used to go there even when I was kid, just run about there. [The parties] used to drive the neighbours nuts, but everyone used to come in, and it was dead friendly. Hughie was actually a very considerate guy, he never used to go on all night, he got on with everbody. And all that was just part of the landscape for me growing up.

“When we were working at Pathway Studios making Metamatic, there were a lot guys coming in with stolen Channel One tapes and making dub mixes of them, quickly – because they were playing as little hourly rate as they possibly could [laughs]. But they were making fantastic dub mixes, and using the studio like another instrument, all live stuff with the faders and switches. Gareth [Jones, engineer and I used to watch and listen and think ‘that’s great’, and we used that, a lot, in the mixing of Metamatic. Because it’s a different genre, it’s not necessarily that recognisable, but it’s dub – a lot of Metamatic is dub. We were trying to get that kind of separation and abstraction between the sounds that the guys used to get. They used to delight in having this isolated sound and having one thing at a time going in each speaker, and then firing an echo across, it was all manual panning, a delight to watch.

The other one was watching Lee Perry down in Basing St. We used to go down to the Island studios there. Lee Perry was great – because he wasn’t dominated by the studio like everyone else was. We used to cower there, and the technician would be the boss and you couldn’t touch anything (‘Sit there! ‘Don’t touch that!’). It was the kind of oppressive regime that was commonplace in studios, with the artist in the background; that was just the way things were run. They’d only just come out fo the white coat Abbey Road generation, so it was difficult for an artist to get in there and go wild with the equipment. And I was dying to get in there. When we saw Lee Perry in operation it was just the opposite – everyone had a job, everyone had a fader, and there’d be twenty guys in there with a fader each, going ‘Come on! More echo! Yeah’ and they’d all be dancing away, and it was alive, the whole thing was organic, everyone working together. And I thought, ‘Now that’s a studio, that’s what should be happening. Oddly enough, that’s what Eno was trying to get to in his own different way.”

“Lee Perry was great – because he wasn’t dominated by the studio like everyone else.”

BE: Eno was down at Basing St as well, wasn’t he?

JF: “Yeah, he went to Basing St, he would have seen all that. Lee Perry was the first. The next guy who did that was Conny [Plank] in Germany, because he’d come up in the same way as Lee Perry, using very primitive tape machines to record live music, in this case live electronic music that was happening around Dusseldorf and Cologne. Conny started with just a four-track and a stereo and built up a studio from there. Anyone who came in, you’d get a job: ‘Right, you, move that fader during the chorus….'”

BE: “Manual automation.”

JF: “It was. And it was great because everyone would be in there working together. You know, Conny was a German hippy, an art hippy, an intelligent sort of bohemian guy who wanted to discover what you could do with all this equipment, which again was totally different to that British technician sensibility. The guys who used this kind of technology best were the liberated ones, who didn’t rely on that kind of hierarchical structure in the studio. Rather than being careful with it – which is the technician’s way, and kind of understandable given how valuable the equipment is – it was a case of pushing it to its limits. ‘What happens when you distort it? What does it sound like when you push it too far?’ We haven’t really got to that stage with digital yet, no one’s really done that with digital in quite the same way – although I suppose you do get people like Autechre and Kid606.

It reminds me of that story – which I may misremember – about the guys from Warp getting LFO’s ‘LFO’ cut by Winston Hazel, and pushing him to give it more and more bass, and him desperately worried that all this bass would fuck up his lathe. You directed the video for ‘LFO’, right?

“That was the result of working through Rhythm King. I’d just been working with Tim [Simenon] for a bit, and Martin Heath [of Rhythm King] knew Warp Records. They were just starting out really, and they wanted someone to make a video for ‘LFO’. I think they’d done just a week’s release, and the single had got very popular – precisely because it was so bassy, everyone thought, ‘I want one of those!’. I knew that all over Manchester at the time it was the record, because it had that bass, everyone was like, ‘Fucking hell. Woah!’ [laughs]. It was quite funny actually, the reaction that track provoked. So it was selling thousands of copies and it had only been out for a week, and they were quite alarmed and they thought, ‘God, if we had a video, we could really do something with this’. Plus they could play the video in clubs as well because clubs had just started to have screens installed, so they rang Martin up and said, ‘Do you know anyone who can make a video?’ and Martin said, ‘Er, perhaps John can…”

“At the time LFO’s ‘LFO’ was the record, because it had that bass.”

“So they said, ‘Can you make a video?’, and I said, ‘Alright then, yeah’. I was living in London at the time but I was teaching in Leeds, doing some lecturing at the art school, and Leeds had a video department – so I got some of the video students and played them the record. One of them, Gary, knew it already, he was like, ‘Oh yeah! That one! Let’s do it!’, which was great. So I got three of them to make animated sections in their own style – I’d seen their work before and knew what they were capable of, so I asked them to do a section each and then we fitted them together. It was all done very quickly actually; we sent it off to Warp, and they were delighted, and that was it.”

BE: “Did you ever get paid for that?”

JF: “Well, that’s another story…[laughs]”

When one thinks of those early Warp Records, it’s hard not to be struck again at quite how many copies of underground dance records you could shift back then in the pre-digital era, when vinyl was the only credible option.

JF: “Oh yeah, the market was massive back then. Especially at that point, because there was a big underground scene right across Britain, it had been going for a couple of years, but that was around its peak or shortly afterwards. It was when Rhythm King started selling 150,000 records in 2-3 weeks, and they were making fortunes, everyone was bowled over by it. You got major labels coming in suddenly with serious finances, because the major labels couldn’t understand what was going on in the street, and Rhythm King had it all – they had Bomb The Bass, and a whole roster of other artists. Plus Rhythm King was carrying a lots of other local independent labels that were putting out amazing one-off singles by lots of artists who would probably never make another important record – but Rhythm King had them all when it mattered. You got everyone from EMI to Warner Bros coming in with silly money.”

“Around that time, computer games were suddenly taking off. The Bitmap Bros had made a game which got to #1, called Gods, which I did the music for, oddly enough. That made even more money, after that the owner of Rhythm King put everything that had been made from the record label into computer games.”

Were you interested in video games themselves, their possibilities?

JF: “Yeah, I was into electronic things, so I thought it was interesting. I never played them, because I’m not a much of a game-player in that sort of sense, but I liked what they could do, and you could see the way that they were going, rapidly, that they were aiming to be – to use the buzzwords – interactive and cinematic, 3D, and so on.

BE: “But presumably the music back then was just that 8-bit sound?”

JF: “Yes, and that was very interesting to do, because what I did was do a lot of things analogue, and then sent them off to a guy who translated them – and that was fascinating, what he did and what he didn’t do. He didn’t understand about music, and it didn’t matter – the results didn’t sound anything like what I’d sent him. Well, it was vaguely similar – there’s a thing called ‘Into The Wonderful’ which still gets remixed now and again that was one of the signature tunes, an 8-bit production, and what we did was get some of those sounds back and then cut them up and re-used them to make more recordings. This was 1991 or ’92.”

“It was a case of people making the best of the small memory chunks that were available. If you did it ingeniously enough, repetition would become a virtue, and you could make something quite beautiful out of it.”

It’s funny how much computer games have become an influence on contemporary producers – from Ikonika to Legowelt, the 8-bit sound is regularly referenced. And it’s not just the sound itself, but the simple, nagging, insistent quality of the melodies, that seem to work really well in a dance music context.

JF: “Back then it was a case of people making the best of the small memory chunks that were available. If you did it ingeniously enough, repetition would become a virtue, and you could make something quite beautiful out of it. Some of the older games themselves I still think are quite good – the obvious ones, like Pong. It’s like a Georgian house, that kind of technology: it can’t get any better – and if you try to improve it, it becomes something else, another mode entirely, and loses a great deal. It’s phenomenally complex minimalism in action [laughs]. The modern games lack some of the elegance of those early games, don’t they? We’re at the baroque end of it now, and that kind of clean design is less common – computer game design has had an opposite evolution to that of typography and art; it’s gone from elegant simplicity and minimalism into baroque.

Tell us about you upcoming live performance at The Roundhouse, the “analogue show”.

BE: “It’s a one-off, so we’ll be bringing as much as analogue gear to interact with on-stage as possible. It is an unknown quantity using this stuff live. I do my own live performances, and it’s only in the last year or two that I’ve started using the synths live, I used to just use the laptop but I got bored of doing that, so I’m now just connecting three or four analogue synths together using what used to be called CV/Gate, which is a pre-MIDI connection – and it works, it’s pretty reliable. So the idea for the show with John is that we’re going to do as much on stage with those connective sequences as we can. But we haven’t actually tried it out yet…”

JF: “That kind of technology is brilliant, but trying to get it to replay sounds perfectly is impossible.”

You’re also involved in a panel discussion with Jim Jupp and Julian House of Ghost Box. Are you a fan of their work?

“Yes, very much so. It’s about memory’s peripheral vision, and I think they’ve dealt with that very well, and very sensitiviely. They were talking to me about ‘false memories’, and about how they get quite a lot of young people who are are interested in their work but who are obviously too young to have glimpsed that world which they reference. But they [the young listeners] recognise it, because they’ve seen re-runs, old episodes of Doctor Who or historical footage of public information films, and there’s this kind of false memory which they’ve constructed for themselves – which is just as potent, if not more so, than the real thing.”

“London hadn’t really moved on since Ealing comedies and Sherlock Holmes and Dickens – we were stuck, and there wasn’t any modern mythology.”

Iain Sinclair is participating in that talk as well, isn’t he? When did you first encounter his writing?

JF: “I became aware of Iain’s work gradually, because of the London thing, and thinking about London a lot. About 20 years ago I was reading someone in one of the broadsheets talking about London, as a city, and saying it didn’t have any mythologies, it wasn’t like New York or Los Angeles, both of which had this film mythology and story mythology, and authors who were very much New York writers or LA writers. From Dashiel Hammett onwards, there were people mythologising these places so that they became myth-lands that we all think we understand.

“But London hadn’t really moved on since Ealing comedies and Sherlock Holmes and Dickens – we were stuck, and there wasn’t any modern mythology. And I thought that’s interesting. Is that actually true, I wondered? And it was. At that point, about 20 or 30 years ago, there really wasn’t a modern mythology of London, it had been cut off around the turn of the century. So from then on I was on the lookout for people who were going to supply that new version of London. I was trying to achieve something similar with music – but I needed other sources, to steal from and assimilate. And there wasn’t anything, really – apart from Ballard, and with him it’s not just London, it’s any city, and preferably something semi-tropical, because that was his point of origin, wasn’t it?

“None of the other authors that came up – Amis and so on – satisfied me, because I lived in London and I knew what it was really like, and they didn’t have the same view. Then [Peter Ackroyd’s novel] Hawskmoor came out – I read Hawksmoor and I thought that’s it, this is a new beginning, really interesting. And then I read the dedication which Ackroyd put in – very fairly and very generously – at the beginning of the book, to say that without Iain Sinclair this subject wouldn’t have been brought to his attention. So I thought, ‘Iain Sinclair, I’ll have to check that one out’. I found Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge, which was marvellous to read, because I lived near Suicide Bridge at the time, and I remember that becoming part of my own landscape.

BE: “What’s Suicide Bridge?”

JF: “It’s over Archway. It’s a massive high bridge that people like to throw themselves from occasionally. It’s a very good way of disposing of yourself, provided you avoid unfortunate people in cars below.

“Anyway, Iain was the one who really began that era of London writing, I think, and I’m forever in his debt. He connects up with Ballard quite happily; he’s one of the major writers we have, and this is his territory, but lots of other people are sharing it now. It’s a nice open-hearted, non-bitchy literary scene, which I like much more than the other stuff, which is becoming peripheral now, mercifully – that kind of parochial, inward-looking London. This is outward-looking, almost documentary London. It’s much more objective. And its connections are much wider.

“It exactly fits in with what I want to do in a different medium. And it started here in Shoreditch, and Spitalfields, which is another nice coincidence – because many of the locations that triggered Iain Sinclair’s interest in London were around Shoreditch and Spitalfields. Of course he was there before I was, but I was there shortly after. And I happened into this strange hinterworld right on the edge of the City, where time had stopped, and you felt that you could access another kind of reality. You could walk from 1970s England into something that didn’t have any particular timescape. It was a very shadowy place in those days, it’s different now, it’s lost a lot, but it’s gained as well, and I suppose it’s nicer to live here now. Back then there were all the guys sat around barrels of burning wood that they’d pulled off the buildings [laughs]. But what was wonderful about it was that you felt you could touch the past – literally. You put your hand on a wall, and that was it – continuous London, without any break, right back to the plague and beyond. It was phenomenally exciting. Just walking around was a big charge – you got a charge from walking around all these dark, dark streets. So that was why I got interested in Sinclair.”

Am I right in thinking that you’re collaborating on some kind of film project with Sinclair?

“Yes, Iain’s got an archive of film that he’s been taking all his life. Even as a child, his parents were filming on Super8 – he’s got all that footage of himself in London, and of London, and he wants to use it in some way. And he saw something I did in Bath, The Quiet Man, and we had a conversation in public as part of the event. Later he said ‘I’ve got this film, would you like to see what you could do with it?’ So he sent me several things that he’d digitised and I’m currently in the process of putting them together to make a film, with his voiceover, and we’ll see what emerges from that. There are other people who might be involved in the project as well, like Jonathan Barnbrook, and maybe my work will intersect with it at some point, we’ll have to see. It will start off very simply, with a voiceover from Iain and his film, and maybe some music from me – recorded sounds and textures from walking around the streets, and some musical pieces – and then I’ll see what’s appropriate and where it can fit.

“I’ve got access to this fabulous archive of this stuff, which is the visual version of his books – it’s like London Orbital on film, really, it’s just superb, magical. I can’t tell you how exciting it is, and I intend to make the best of it.”

“There were strict demarcation lines back then – you wouldn’t find any of the bankers in the Shoreditch pubs that were literally yards away from their offices.”

You founded a studio, The Garden, not far from where we’re sat now. Was it a deliberate decision to establish it in Shoreditch?

JF: “It was just an accident, because it was cheap. It was recently vacated by industry, when we went there in 1980 and bought the building – which would be impossible now for an arts-type guy to do, buy a whole building. Seems incredible now. So we kitted it out with some individual studios and started work – we were the only people here [in Shoreditch]. There was Dennis Severs who lived by the market, who was rebuilding the house, he’d been there since the 60s, and Gilbert & George, and one or two other people, but apart from that it was largely empty. The market was still going, Spitalfields Market, but it was a deserted part of London. All the warehouses were empty, and all the small factories. What we were in was a former clothing store, a small East End department store. You’d just walk around [Shoreditch] and think, ‘Wow? What’s this?’ and try to make sense of it all, because it was nothing like anywhere else I’d been in London. It was closer to the North – that was why I recognised it, because it very closely resembled parts of Manchester and other derelict factory towns left over from the cotton industry.

BE: “What’s interesting was that the City was so close…”

JF: “Yes, exactly. There were strict demarcation lines – you wouldn’t find any of the bankers in the Shoreditch pubs that were literally yards away from their offices.”

“So you just walked into and out of it, like another timezone, like Doctor Who or something. And I loved it because it was forgotten. I always wanted to live here, because you felt like you could go into another zone. It did affect you mentally, and emotionally, that change. It was quite dramatic, I think.”

A lot of other bands and artists recorded there at The Garden as well. Were you involved in the studio work or were just renting out the space?

JF: “Well, I did both. Those who were friends and who I knew well enough would say, ‘Do a bit on this record’, so I’d add a bit of backing vocal or play something, and the rest of the people I just gave the keys to and asked them to phone me when they finished. It was as open as that.”

“That’s what London does: it changes all the time. It’s very fluid. Eras and areas are shifting around perpetually.”

How long have you had your studio here, Ben?

BE: “I’ve been here five years, but it was a studio before I was here – a Japanese studio for Japanese artists in London. It’s been here since the mid-80s, I think. Only in the last two years have I really been using the whole space. We used to do more commercial stuff, TV music, but in the last two years I’ve stopped doing that and concentrated on album projects instead. The band Tunng are based in the room next door – Mike used to work for me doing commercial stuff.”

Have you registered much change in the area yourself?

BE: “I got here after the White Cube. Once the White Cube was established, that was when [Hoxton] really changed. Before that you just had the Blue Note on the corner [of Hoxton Square]. It really changed seven or eight years ago when the Square changed. It was already pretty vibrant when I got here. What’s changed in more recent times is that the people who come here to socialise are coming from a much wider area, to come and drink in the bars, so you can’t move out there on a Friday or Saturday night. I actually like it – I think it’s really cool that it’s so vibrant, but I know plenty of people who’ve been here much longer and can’t believe the change, just hate it. But then I don’t actually live here, I just work here.”

JF: “That was why I left. I used to live in a quiet street, Broom Street. It used to be nice to go into a pub and sit down and read a paper, but you can’t do that anymore, it’s gone. It’s not really a living space anymore, it’s more of an entertainment space, and that’s fine – it’s great to see that, because that’s what London does, it changes all the time, it’s very fluid – eras and areas are shift around perpetually. I mean, Portobello Road was derelict at one point, Notting Hill was one of the worst bits of London at one point – you wouldn’t have wanted to be there back then. And then the market got fashionable in the 60s and suddenly it was like this [Hoxton] – this now is the equivalent of Notting Hill then.”

Speaking of a loss of tranquility, can you tell me a bit about your two most tranquil albums? Cathedral Oceans and the Harold Budd collaboration, Translucence + Drift Music.

JF: “Cathedral Oceans started when I was kid, when I sang in a choir briefly. During that time I became very interested in the way that sound worked in big spaces, churches particularly. I learnt a lot of things there but I didn’t understand a lot of what I’d actually learned until later. And when I started recording I’d almost forgotten about all that until I started using echoes and reverberations, and then I realised that I could use some of that to simulate things that happened when I was singing in churches back then – and use that old knowledge of how a single voice in a massive space behaves. So I started experimenting, down in the basement of the studio, and when I had some time I used to get Gareth to set up tape-loops and reverberations and I’d sing into them and see what happened, and gradually negotiate my way through it. Over the course of many years Cathedral Oceans began to take shape – it did take a long time. In the meantime I could hear happening, in the stream of things going by, other people who were beginning to work in the same way.

“I became very interested in the way that sound worked in big spaces, churches particularly…”

“I started taking photographs of buildings and statues, beginning when I was on tour with Ultravox. I didn’t know what to do with any of these things. And then one day I picked up two slides and overlaid them – one was of some foliage, and the other was a face from a fountain statue, and you suddenly got this other reality coming through, which was unusual then. Nowadays Photoshop can do it very easily, but back then that kind of montage really wasn’t easy to achieve. It really inspired the musical juxtaposition – of that old-style church music with modern technology and synthesizers and different ways of singing, creating notional space rather than real space. So I started working in parallel with these two things and gradually built up a library of images and pieces of music.

“I was trying to do a live version of Cathedral Oceans in Vauxhall, and Harold Budd and Eno came to listen to it. Harold liked Cathedral Oceans a lot and we started talking; I was really into his stuff because I loved The Pearl, I just think The Pearl is one of the greatest pieces of recorded music ever made, a real classic, a landmark. So we got talking and we decided to do some work together. He came over; I was staying up in Leeds then, and I had access to this big stone house there that belonged to a painter friend of mine, Judy, and she let us use her front room which had a beautiful view of the garden. I recorded Harold playing there, and then recorded some pieces of my own. I was trying to imitate his style – what you’d call a tribute [laughs].

“Harold has really affected what I think about pianos, and piano music, more than anyone else – apart from Erik Satie. And that’s an old art-school thing, because I came across Erik Satie when I was about 16 in Preston, when a girl, a friend of mine, Liz, played Gymnopedies on the piano in the lecture theatre – and that just knocked me for six. It was fantastic music, the first time I’d heard it – I still find it very moving now, and I’ve never forgotten it. And when I heard The Pearl that was like a modern equivalent – I thought nobody could ever do [what Satie had done] again, because that was 1900 in Paris and a whole different culture, and then suddenly there was somebody living in Los Angeles who picked up on that, met up with Eno, and made this great record. So it was a wonderful moment.”

In a way I think is Budd all the more impressive because his work is created in the context of a much noisier and distracted world than that which gave rise to Satie…

JF: “You have to be tough to hold onto something as fragile as that, and he’s done it. I really admire Harold. He supplied the musical end of that record. I think the ecology of that record is very interesting because you’ve got someone like Harold, who was working to maintain that kind of stillness in the midst of all this chaos and cultural movement, but then you had Brian who wanted to do that but didn’t have that kind of musical focus really. And then you had someone like Dan Lanois – who’s of the best realisers of notional space that you can ever get, there’s just no one better than him – all together in one room to make this record. So it was a great balance of talents – perfect. And they made as close to a perfect record as you can get. Whatever that means. At the very least it’s a perfect realisation of an emotional state, and it will endure for a long time, well, forever – it’s up there with Satie.”

Translucence and Drift Music feature quite prominent synthesizer work from you as well, don’t they?

JF: “They don’t, actually, though I can see why you might think that. What I wanted to do was disperse all the piano harmonics as much as possible, by using reverbs and echo, and just take it as far as I could. Right into abstraction.

BE: “So there’s no synths? It’s all reverbs?”

JF: “It’s all derived from piano. No synths. All that effect is from reverberation and echo – and it’s interesting what happens if you push them to that extent, because they begin to create their own sort of ecology.”

“All that effect is from reverberation and echo – and it’s interesting what you happens if you push them to that extent, because they begin to create their own sort of ecology.”

It’s particularly amazing to think that Drift Music has no synths on it.

JF: “Drift Music is more abstracted, yes. You sort of go in for this state which is texturally shifting without any dramatic harmonic shifts – so it’s a lack of drama, really. A music without drama.”

Does it require a special physical setting to make this kind of intensely serene, strung-out music?

John: “Yes, and mental, definitely. You do get into a trance state when you do it – time just dissolves. It’s very contemplative. Not meditative – that’s a very artifical-sounding word. But yes, it slows you down, and you go into a completely different mode. And you have to be in that mode [in order to make that kind of music]. But it’s a lovely mode if you’re ready for it – you usually have to walk three or four miles before you sit down to it, because otherwise you’re too restless; you have to do something physical first, go for a swim, or be up all night.

“Early in the morning is the best time to do it – I did a lot of recording at dawn, in summer. Because you’re sort of half asleep and some of your critical faculties aren’t working properly and you’re calm enough just to drift along for a couple of hours. It was really interesting to do, and it links up a bit with Cathedral Oceans – that was like that, when I’d sing into those loops and so on, I’d get into this completely different time-state, and I’d be working with rhythms where sometimes the beats are a minute long (if they were beats – there aren’t actually any beats, it’s just a repetition) and you start to work inside that, within that. So your whole metabolism just slows right down and you can be there for hours, and it seems like minutes, you lose your sense of time. It was very pleasurable to make, it never felt like work, it was almost like gardening really [laughs].”

Kiran Sande