It’s 2016 and music writers are scrambling to prepare their pitches for the 20th anniversary of albums that dropped in 1996.

This is particularly true for hip-hop, as that year brought fans The Score, Ridin’ Dirty, Reasonable Doubt, ATLiens, and All Eyez On Me, to name a few. Rappers across the country were in their creative prime, and the year is rightly considered one of the most influential in the genre’s history.

Ask any rap fan and they will tell you (probably unprompted) that 1996 falls within the “Golden Age” of hip-hop. The exact dates are malleable, but the consensus is that rap hit its stride in the early-to-mid-1990s. By about 1992, the genre was mature enough for artists to feel comfortable developing personal styles and for regional sounds to flourish. Hip-hop managed to hold off full-on major label colonization and corporate marginalization of creativity until around 1998. It’s not a perfect argument, but the logic is solid, and it’s hard to deny that the era produced a disproportionate number of iconic albums that remain impactful to this day.

“The real Golden Age was when the boundaries started crumbling: the early 2000s.”

The problem is that the “Golden Age” only looks golden in retrospect. A list of albums from 1996 now seems like a self-evident case for the year’s importance. But in 1996 the average rap enthusiast would have told you without hesitation that half of those albums were wack as fuck. The coastal wars were still on: it was real quiet for anyone riding for All Eyez On Me east of the Mississippi, and vice versa for Hell On Earth. Fans of Reasonable Doubt were ready to fight over the idea that Ridin’ Dirty was worth their time, if they had even heard it. Beats, Rhymes and Life was aight, but not a proper follow-up to Midnight Marauders, with questionable production from some newcomer named Jay Dee. And the less said about Nas’s jiggy turn on It Was Written, the better. Shit, Endtroducing… had a track called ‘Why Hip Hop Sucks in ‘96’, and why hip-hop sucked in ‘96 was basically the premise of Stakes Is High, which itself had a shaky reception.

For all its merits, Golden Age hip-hop was Balkanized and provincial, preoccupied with the genre’s future and terrified of alternative approaches to the music. This trend continued through the ‘90s, with every rapper pigeonholed for their region, their gender, their content and their associates. Underground rap coalesced into a movement in indiscriminate opposition to so-called “commercial” artists, but never did a great job explaining what differentiated the two sides other than mainstream success. Complicating the problem was the difficulty in actually hearing the music you weren’t supposed to like. Regional bias skewed all major media towards the coasts, and the smaller, independent empires across the country had no real incentive to build fan bases to far-flung listeners beyond their distribution deals or their trunks. The music traveled when fans went off to college, to military posts, to visit relatives in other regions, or to buy dope where it was cheaper, but not efficiently enough to build national fan bases.

The real Golden Age was when these boundaries started crumbling: the early 2000s. The years from 2001 to 2006 were defined by collaborations against type and regional stars finally reaching the mainstream. Kanye West led the charge, rapping about both social issues and material success with a flow that redeemed the oft-maligned Mason Betha, and doing so with the co-sign of Jay-Z and Common. It’s easy to see his wide range of customers and collaborators as a result of his hunger: the Kanye we know would understand that the road to stardom is paved with production credits for Made Men album cuts and uncredited Nas loosies. But his pragmatism framed all of hip-hop as a continuum, and his ability to tailor his style to everyone from Trina to Consequence displayed common ground between previously unthinkable realms of rap. Freeway and Mos Def don’t seem so far apart in 2016, but hearing them go verse for verse on ‘Two Words’ (the B-side to ‘Through The Wire’) in 2004 was revolutionary.

“The Diplomats took over New York by slaughtering any and all sacred cows.”

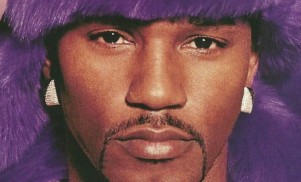

While Kanye brought disparate artists together either by collaboration or by juxtaposed collabs, other rappers spent the early years of the millennium challenging the paradigms that kept hip-hop separated by geography. Already prospering with a new Southern flow imposed on him by a bullet lodged in his soft palate, 50 Cent envisioned G-Unit as a crew without a region. In Lloyd Banks, Young Buck and Game, he found artists from the three major corners of the map and blurred all their differences with help from Dr. Dre’s post-regional executive production. Meanwhile, The Diplomats took over New York by slaughtering any and all sacred cows. In the face of Real Hip-Hop values, they flipped ridiculously cheesy samples, rhymed words with themselves, and openly fraternized with even the most locally despised rappers. (It didn’t hurt that they were rapping their asses off in the process.) If Cam’ron and friends didn’t have the audacity to remake ‘Bout It Bout It’ with Master P in 2003, A$AP Rocky would never have declared himself “so ’bout it ’bout it I might roll up in a tank” in 2012. It’s no wonder Yams got his start interning with The Dips.

The counterpoint to Dipset actively challenging notions of hip-hop orthodoxy was the long overdue recognition of rap talent in secondary markets. The most visible was Bun B, whose quest to not let UGK languish while Pimp C was locked up resulted in countless guest verses and the duo’s eventual exaltation. E-40 finally got his due for his incredible longevity, his revolutionary style and, of course, his numerous contributions to the lexicon. And while Ludacris wasn’t overcoming a decade and a half of regional bias like 40 and Bun were, the way he held his own with Nas and Jadakiss on the ‘Made U Look’ remix in 2003 is as good an argument against the idea that the South doesn’t have bars as anyone ever made. Rap fans also spent the early 2000s revisiting and discovering the likes of Juvenile, Project Pat, Trick Daddy and Trina, among too many others to name. That’s not to say any of these rappers weren’t moving units or spitting fire before the new millennium, but there was a strong regional bias working against them. Without this adjustment period, it’s hard to see anyone taking seriously the argument that Lil Wayne was the best rapper alive. (It’s also hard to see ‘Still Tippin’ becoming the sensation it did, or Three 6 Mafia winning their Oscar.)

Not everything that happened in rap in the early 2000s was perfect. The cults of Dilla, Doom, Madlib and 9th Wonder sucked up all the attention in the previously flourishing underground. Roc-A-Fella fell apart, hyphy never took off, and Ludacris never put a good album out. Chamillionaire and Paul Wall never made a follow-up to Get Ya Mind Correct. Cannibal Ox never made a follow-up to Cold Vein. But it was a great time to be into rap, an optimistic era when the genre really felt like it had unlimited talent, creativity and intelligence. Artists you loved reached new peaks, and artists you thought you hated snapped into focus and bodied unexpected guest spots. 1996 gave hip-hop fans a lot of incredible music, but it came with a lot of rules. Golden or not, we should be glad it’s not 1996 anymore.