The story of any one local music scene is always fraught with details and intricacies that are often lost to anyone who wasn’t there once that scene explodes beyond its limited geographical reach.

In the past decade, the Internet has helped to make such local scenes into global phenomena quicker and in ways previously unimagined – a process that has hastened the loss of details and history while providing a platform for anyone who seeks to give accurate historical accounts of what happened, and how.

Los Angeles’ reputation as a creative hub for underground, forward thinking music is on a par with London, yet the history of the city’s club scene is still perhaps one of its best-kept secrets (and I’m not talking rock here). After spending only two weeks there doing research recently, I came away with a sense that the history of hip hop and dance clubs in the city is a deep and intricate one, rarely discussed in detail beyond its most famous exponents.

Take the so-called ‘beat scene’ of the late 2000s and its most famous club, Low End Theory. LET is a globally known name, arguably on a par today in terms of cachet and myth with the DMZ dances in London that helped cement dubstep’s global foundations just a few years before LET blew up. Looking at what came before LET provides an understanding of how the party, and the scene that grew around it, were the logical evolution of a bubbling underground hip hop and alternative scene that sought the new and exciting with the same fervour as their European counterparts.

Kutmah is a DJ and artist raised in Los Angeles who in the late 90s and early 00s became an intrinsic part of that scene’s evolution and growth, both as a DJ and the driving force behind the Sketchbook nights, LA’s first beat party as we understand them today. Having relocated to London in 2010 following troubles with his legal status, he’s now found a new lease of life after the scene he helped bring out blew onto the global stage while he stayed stranded behind in a city he couldn’t leave. I recently sat down with him for a lengthy conversation about his origins, the early days of the L.A. scene, and the clubs, places and people that helped define his artistic aesthetic, vision and work.

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 1/6)

Growing up in L.A, how did you get into DJing?

“I was really musical, like most people I guess. I mean who doesn’t like music? Basically right out of high school I moved to Los Feliz, a really cool neighbourhood. I lived there and worked in this clothing store called Jetrag. There was this dude who also worked there called Culture D, Damon. He was a dancehall DJ and he would always play mixtapes. At the time I was listening to a lot of punk, Sonic Youth, PJ Harvey, that’s what I was really into. I also used to skate and what not, and there’s so much music I remember first hearing in skate videos. So Culture D used to teach this girl called DJ Kiko who also used to work in the shop, and she had tables at her house. She would let me go over and try and practice. No one ever gave me any help, I always learnt on my own. No one ever said anything, not a single thing. And at that time we were just going to hip hop clubs.”

“I started DJing in 1997 so this is probably 1995, or early 1996. I got fired from the shop because of my legal situation and it was hard to get another job. I got unemployment for six months, bought turntables and just practiced trying to make one nice tape. I gave it to my friend Praise One, who used to play at a night called Firecracker. He would play leftfield stuff and I was really into that. He would play just the beat of a track, things like that. I was hanging out there and one day he asked me if I wanted to open the club, and I became their opener for five years or so. That was fine by me because I think there’s a skill in playing first for an empty room with people walking in uncomfortably, you know? Firecracker was a hip hop club, in Chinatown, and everyone played there. Peanut Butter Wolf, I remember him playing the first Quasimoto records there. Madlib also played. We had the anniversary and Kenny Dope played. Biz Markie was a guest, 9th Wonder. After a while I started getting into a lot more fucked up stuff like Prefuse and on a Friday night most people don’t want to hear that. So it was hard to… I didn’t have to switch up my set necessarily but I had to think about what to play and I had all these records I wasn’t able to play. I wanted to have a night to do that and this is how Sketchbook got going.”

How soon after you began to feel like this did Sketchbook start?

“Sketchbook didn’t start till 2004 but I had the idea before. I was getting frustrated with hip hop clubs… Not that I wanted praise or anything but I got sick of girls asking for fucking pop songs. Plus it’s Friday night, I know they just want to have fun and shit. Around this time my man J Logic did a party called Sound Lessons which was also a hip hop club and he would let me get away with more beats, he got amped on the beats. Same thing though, after a while… that was a Saturday night club too so you definitely can’t be too weird there.

“One day I’m hanging out with my homegirl Oka-san. She used to work at this dive called The Room in Hollywood, and I would hang there. You’d have to walk down this alleyway, no one could find it unless they knew it was there. It was really small but long, so not a lot of space, and they used to play dancehall. I remember DJ Daz used to play there, and I would just go and draw. Oka-san would give me free drinks and I would give her a drawing, and we would just hang out. Then one day she asked me if I wanted to do something every Tuesday, so we tried it, and that’s how Sketchbook was born. It was dope. It was just drinking Hennessy at 9 o’clock. We’d get there around 8, set up, I’d print up Xerox copies of my sketchbook, make a collage really quickly. I’d made a sign that said ‘No Requests’, a massive sign so no-one could get it wrong. It was a nice little thing, dancefloor was tiny and if you had 3 people dancing it was fun. That was 2004, myself, DJ Nobody… ”

I didn’t know Nobody was involved.

“He would come and play because he was living in Long Beach and whenever he was in L.A he would play if it worked day wise. Then there was Take and Orlando Renault as residents too.”

What about Coleman? I’d heard he was also a resident.

“Coleman [ed note: one half of Mochilla alongside B+] was a resident at Firecracker. He was the one who really… he influenced me. Him and J Rocc are probably my two biggest influences, style-wise. The way they mix, holding the mix down. They play hip-hop the way people play house. But yeah, Coleman was another resident. He also makes beats, and there’s a great picture of him in the studio with Madlib and Dilla, him just chilling with the masters.”

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 2/6)

How did you meet Tom [Take, now Sweatson Klank]?

“He probably doesn’t remember but we first met at Fat Beats. I asked what the record playing in the shop was, and he went like “ah yeah it’s mine”. To be honest I can’t remember if he said it like a dick but I remember that moment… going into Fat Beats back then, they didn’t know who you were and they didn’t care. I was probably wearing like a Minor Threat tee shirt. I didn’t look like a hip hop head, or whatever, I still don’t. But that was the first time we met, I think I even bought the record.”

It was under Take One right?

“Yeah. It probably burnt in my house actually. That was the first time knowing of Take basically. Then I used to go to Aron’s Records and he worked there. aron’s… That was the Mecca right there.”

Talking to Take and Ras G before, I got the impression that Aron’s was an important early spot for a lot of people who would become part of that whole scene in the following decade.

“Early on for sure. Aron’s isn’t around anymore because of Amoeba. There was nothing better than Aron’s man. When it closed it was heartbreaking. It was a mom and pop’s record store. Tom was a buyer there, and I’d seen him around a few times since Fat Beats. He had a hip-hop night called Square One around that time, it was at Star Shoes on Hollywood blvd. I think I went like once, saw he had cuts and shit. He was a really good DJ. So we started talking about what we both wanted to do and then this spot at The Room came up and that’s more or less how it all started.”

Tom had mentioned about how you guys would sometimes go through the distro list at Aron’s and pick out weird records you wanted to hear.

“Yeah we did that a few times. Aron’s was like the spot, like in Cheers, where you walked in and you would say hi to ten people. It was that kinda spot you know. I’d go there and spend hours listening to stuff.”

Who did you meet there?

“Sacred used to work there [ed note: legendary LA DJ and producer involved with the Soul Children]. I think I saw Ras G in there like three, four times before we first met. I’d see him in the experimental section, so I’d ask Stan [Sacred] :yo what’s up with the Rasta in the experimental section? Is he lost or something? What’s he doing?” (laughs) That’s when Sacred told me who he was, told me to check out his music. And I think one day we ended up both holding the same record… I was in the downtempo section, but there was, you know, Dimlite in there, which isn’t downtempo! It was before they’d made up more shit names for it and they still don’t have a word for it actually. But yeah that’s how I met G. We started talking and it just clicked. I think it was a hip hop 12” we both held, and he was like “oh yeah that’s a good record” to which I replied “the rhymes suck but the instrumental is dope” or something like that. Then it was like “oh you like beats?” and it was on.”

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 3/6)

Would it be fair to say that all you guys – Tom, Ras, Nobody etc… – shared this common thing where you liked hip-hop but didn’t always dig the MCs?

“For me it was one of those things where I wanted to mix whenever I wanted to mix, I didn’t want to have to wait for the hook to come in to start mixing. When you have the instrumental you can dive in, it’s more fun to play with. You can ignore certain things as long as it’s still in time or whatever, which half the time I wasn’t, so I’d just dive in. It was more fun, and I think that’s partly why I got into instrumentals more. I wasn’t feeling the MC and I didn’t want to have to wait for the hook.”

“Actually I just thought of something that’s really important. There was this club called JuJu that Sacred played at, with Rome and Al Jackson. It was in Leimert Park, which is hood as fuck, and it was just a Saturday night party. No alcohol but they’d make their own drinks with ginger and stuff like that. It was the kind of place where they would play a Dilla beat, Jay Dee beat back then, for like four minutes and everyone was cool. No one listened with their ears or eyes, people were just vibing out, everyone was just… it was the best fucking vibe of any night I’ve been to, still not been beat. Sacred was the first one to play Dwele. He went and found this track, I can’t remember which one, right around the time we’d first heard of Dwele after Carlos Nino had played him on his radio show. So we’d all heard this song and Sacred goes and presses up this shit on 12”, then plays it the next Saturday! He was that dude. He’s got a sick jazz collection too.”

“He now works in this store called Frequency, probably the only record store in Los Feliz. Juju was the night, man. The hottest girls you’ve ever seen in your life, everybody was cool as fuck, everyone smoking weed. There was no bullshit, the best fucking vibe. I’m a mixed race kid and it was nice to not feel… if you go to a black club you feel the difference. And I went to this and I didn’t feel shit there. It was one of those things, where you didn’t know how you were going to be treated you know?”

Was it segregated in L.A. then?

“Not that bad no, but you didn’t know how… I’d go to dancehall clubs and get treated like shit. But anyways there were a few other key nights I used to go… My man Chris Vargas and Frank Sose used to have a night called The Bridge, which was Tuesday nights at the Viper Room and J Rocc would play four hours. This is probably 1996. Because it’s the Viper Room people wanted to hang out with Axl Rose or some shit and no one went to listen to hip hop. So there’d literally be twenty people there and J Rocc killing it. It was the kind of moment you’ll never get again. Just hearing a second of a tune, guessing what it is. You know how J plays. It was a proper schooling for me. All the Beat Junkies were sick but J Rocc was the one for me really.”

How did you hook up with Dublab?

“I had a high school friend of a friend who found out I was a DJ and asked me if I wanted to come see his friend who had this internet radio show, which was Dublab. I was really into DJ Spooky, Portishead then. I was playing that kind of stuff, weird records from Bali, I was a bit all over the place. I went to Dublab and they had a camera on me the whole time. I was freaking out, especially because I didn’t really know what I was doing that well. That’s when I first met Frosty. He told me to come back and they just started having me and offering me a radio show. I agreed not really knowing what that meant. I didn’t know anyone who would want to listen to that or even anyone who was listening. Frosty was always yelling at me that I needed to talk, get on the mic. I was just stoned and I wanted to play records, I didn’t really care, I thought the one person that was listening didn’t either. Which is funny because now I’ve been out of the country I’ve met so many people who comment on that show and bring it up.”

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 4/6)

[At this point the recorder loses some of our interview, we come back on the subject of Coleman having done the shots for Company Flow’s Little Johnny From The Hospital cover]

I spoke to El-P a couple months ago and he mentioned they got a lot of hate for putting out an instrumental record in 1997. Looking back it seems a lot of people weren’t ready for instrumental albums then, at least within the wider underground hip hop sphere.

“Yeah but you have to give it up to Shadow as well, Endtroducing really fucked my head up. It’s still sick. Also Dr Octagon. Prince Paul with Psychoanalysis, which I think was one of the first to use that idea of beats for a whole album. Only thing I didn’t like on that album was the ‘Perfect Night for a Date Rape’ song. But he’s Prince Paul. It was the shit.”

That came out on Wordsound and then again on Tommy Boy. Were you into Wordsound?

“I was into Spooky and all that illbient stuff, so I did hear some of the Wordsound stuff. Do you remember the El-P remix on the Techno Animal album? That’s the hardest shit. Mr. Oizo also. He was the first one to really fuck with that distorted sound. Techno Animal to me was just harsh, some of it anyways. And coming from a punk background I really dug it. But Mr. Oizo, I still play that record.”

That reminds me, Tom mentioned this thing you guys had about playing records at the wrong speed. You did that with ‘$tunts’ right?

“It was because I knew I couldn’t play a James Brown record at the wrong speed because everyone knew it. Same with say Pete Rock. But no one knew this weird shit I was finding so I started experimenting with it. I didn’t know anyone who played $tunts but I found the 12” for 99 cents when it came out. No one gave a fuck about Oizo back then. And I wasn’t trying to hear or play shit that fast, so I just pitched it down and because it was pressed at 45, I slowed it down to 33 first and then put it at plus 8 and you reach 100 bpm.”

“So because no one knew those beats I could get away with doing shit like that. And then how much hip hop is at a 100 bpm? EPMD, all that shit. My way of tricking… that’s when I started playing a lot of these beats over vocals. That’s what I would do a lot. Play a beat, play a vocal, play an instrumental, play another one, etc… We did it with a lot of house records and dancehall. Just buying records to see what they sounded like slowed down. It’s also a good trick for sampling, it’s how you get nice fat kicks.”

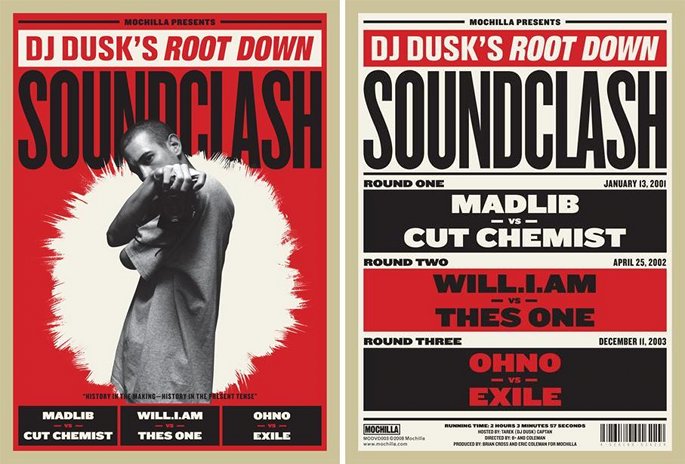

Going back to the pre-Sketchbook era for a minute. You once mentioned to me how influential the Root Down soundclashes DJ Dusk had put on were. Having seen the documentary of it that Mochilla released, they seemed like an incredible moment in time.

“Yeah, that’s the moment I realized I wasn’t stupid, I wasn’t retarded. The first one was Madlib and Cut Chemist and being a huge fan of Madlib just hearing all these beats and seeing people going mental for it was incredible! And with no MCs. But the Oh No battle was the one for me. Oh No’s stuff you can bump in the club, Madlib is sometimes not so good loud. The first one happened at the time of me doing opening sets at Firecracker and feeling unhappy with how things were going like I said. I was thinking I was playing good music and I wasn’t getting any love for it. On the night of the soundclash I knew every beat being played. They would play beat to beat. I was like ‘I mix those records’ and I thought ‘this is it, let’s try this night idea’. Luckily Oka-san then offered me the spot at The Room and it made the whole idea for a beat night valid. Orlando and I used to think we were retarded, why did we like this music that no one else did? And seeing the soundclash, seeing people get down, people I didn’t know, it was cool, it was how it should be.

“All these nights I’ve mentioned were the clubs going on before Sketchbook or any of what came after. And you know what happens with clubs: you go there for five/six years, become a die hard fan, meet a girl, get her pregnant, stop going out, life catches up with you etc… so all these clubs started dying out. Not saying Sketchbook replaced any of them but these are the clubs I went to, and which informed what I did after.”

We’ve often talked about many of the influential tracks from this early to mid 00s era. One that keeps coming up in our own chats and with others is Danny Breaks’ ‘Jellyfish’.

“‘Jellyfish’ fucked our heads up! ‘Jellyfish’ was the one, it was the only tune I got love from Cut Chemist for dropping. Cut Chemist’s studio was round the corner from Sketchbook and so he would hang around sometimes. He didn’t say hi or anything, didn’t know us, but I played ‘ ‘Jellyfish’ once when he was there and he came up to the booth and just started chopping up the record from the other side. I was like “oh shit”, and then he was telling me how this beat is fucking crazy, how Numark had been playing it…”

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 5/6)

Why did you think the concept behind Sketchbook, giving people sketchbooks to draw on, was so important?

“Because I don’t like talking to people when I go out. If I got out to hear music and someone’s talking to me about their day job I’m not listening to the music anymore, it’s like you’re a psychiatrist all of a sudden. Going out it felt like there was a lot of that going on, people getting drunk, coke etc… people talking out their ass. We were all weed heads, just wanting to hear beats. There were of course people talking and shit, it was like any club, but you’d see ten people just sitting there drawing, two people together doing something else, it was really cool and a nice way to break… to just go out. Everyone is insecure, has their own issues etc… it’s kinda hard to meet people so this was a nice way to have non-verbal communication and hang with a total stranger next to you at the bar. That’s what I liked doing. I’d go to the club and sit and draw for four hours. I’d get shit drunk and take the bus home. Or drive home like we do in L.A. But that was it really, it wasn’t anything else… at the beginning I felt like we could do art shows but people just drew penises mostly. I’d d record sleeves over and over and every week there’d be new penises, like ‘who the fuck is drawing all these penises?!’ It was really weird.”

Tom also mentioned this healthy competition between you two, in terms of finding records that the other didn’t know about, playing stuff at the wrong speed and so on.

“For sure. He’s a better DJ than me. When I started DJing in 97, L.A. already had J Rocc, who’s the best DJ on the planet. I don’t care what anyone says. Beat Junkies too, Babu, Melo D, D-Styles, all these dudes. How am I even going to get through here? That was another reason why I started to fuck with these beats, because these dudes didn’t. And I loved this shit.”

Ironically now a lot of them do.

“Right. That’s the funny thing. I used to have a radio show with Scion, it was a three-hour radio show, my man DJ Haul hooked it up. I just played a little of everything, whatever. But then during that time Daft Punk was huge and Steve Aoki started coming up and I was really against this trendy stuff. They would have the “best show of the month” and it would be someone on Daft Punk’s dick. They would tell me to stop playing beats, play less hip hop and just play Joy Division and stuff like that, which I love, but three hours is hard to fill every week just playing that stuff. And now I’ve seen them do shows with Daedelus, Gaslamp and it’s funny to see. But it’s nice to know you were right. That’s the only way to put it. No one’s wrong, they’re just late.”

You switched venues for Sketchbook halfway through its lifespan right?

“We did about a year at The Room. You can’t go there now, it’s like bottle service or some shit. The main reason is that Oka-san left, they started renovating the place and that was it. She was our… she was the homie. She left and the owner was like ‘you’re not making us any money, we don’t care how cool this is’, so we got the boot. We moved to Little Temple, which was beneath the Dublab studio, near the Los Feliz end of Santa Monica, corner with Virgil. Some nights would be amazing and some would be dead to be honest. And this is at both places. It’s Hollywood, sometimes it’d be slow.”

I also heard about some of your guests. Including Prince?

“Ah yeah, that was through my homegirl Rashida. She was a local DJ who’d made a name for herself and ended up being the DJ for Prince. Actually she’s Kelis’ DJ at the moment. She’s also on my 10”, she’d leave me phone messages and I’d tape her voice. You can hear her voice on there a couple times.

“Anyways she calls me on a Sketchbook night, it was rainy, slow, the end of the night, there was ten people there. She tells me she’s coming by with someone. And she walks in with Prince! We’re playing Dilla and Dimlite and shit like that, so she’s like ‘Prince wants something he can dance to’. I’m like ‘What? He’s fucked! What do you mean?!’ The only thing I had that was close was Let’s Ride by Q-Tip, which wasn’t what he meant at all. So she’s telling me he’s not into this. It’s also super awkward because they’re dancing in the middle and everyone is like “oh it’s Prince”. It was a disaster actually. They stayed for ten minutes and left. But still Prince came. Prince came to my club.

“We also had Caural play live. Ge-ology also came through, that was all at Little Temple. Tom hooked that one up. Daedelus played quite a few times at Little Temple too. Lotus played as well, that’s when we did the release party for Sound Of L.A., which was thanks to Carlos Nino, who used to do bookings at Little Temple alongside Dexter Story who’s also a part of Life Force Trio with Carlos. They liked what we did so they let us continue even though we weren’t making any money. Blank Blue also played, Nobody’s project with Niki Randa.”

What about the infamous boom box that Dibiase would bring and on which people would play their beats outside?

“What happened is that people would hang in the parking lot of The Room, smoking weed in each other’s cars listening to beats. At one point Dibiase brought the boom box out instead of having it in his car and that’s when it started. When we moved to Little Temple the whole thing really kicked off though because you’d smoke outside to the left of the venue. There was a dirt pit, on the street, cars going by. It was usually Dibiase and Ras outside smoking weed. A lot of people’s beats got played on that boom box, a lot of history.”

How did Sketchbook end? Tom mentioned it just fizzled out.

“I didn’t really like Little Temple, the vibe wasn’t the same for me and there was no money being made. I was broke and I had two friends who used to come, really sweet guys who were into house and shit and we were their alternative night. One night one of them got stuck up, a gun got pulled on them. The venue was in a shady neighbourhood. So my friend got stuck up and I was like, if he’d died… it was all friends coming you know? My girl came to this. I started thinking. It happened twice, to someone else as well. I wasn’t going to wait for some shit to happen, it felt better to stop it. I was like, “we’re done.””