Don Buchla, the West Coast pioneer who was at the forefront of synthesiser innovation in the 1960s, died on September 14 at 79, from complications related to cancer. Oli Warwick talks to some of his devotees, from early adopters such as Morton Subotnick and Suzanne Ciani to newer disciples like Surgeon, to find out what made Buchla such a powerful force in experimental electronic music.

For those versed in the language of early synthesisers, there exist two schools of thought: East Coast Synthesis and West Coast Synthesis. The East Coast approach was pioneered by Bob Moog, whose designs were geared towards traditional, keyboard-minded musicians. Over in California, however, Don Buchla sought to break away from the pre-existing musical conventions and create instruments that encouraged intuition and experimentation. The two independently developed their first modular synthesisers within a remarkably short timeframe, and while Moog machines would go on to become a familiar fixture across the musical spectrum, Buchla equipment has tended to appeal to a more niche crowd. As techno producer and late Buchla adopter Surgeon suggests, “there’s something about Buchla instruments that attracts odd people.”

Buchla spent much of his youth in his native California, eventually studying physics, physiology and music at UC Berkeley. His early experiments with sound followed musique concrète principles of tape splicing, but in 1963 he was approached by Morton Subotnick and Ramon Sender, founders of the influential San Francisco Tape Center, to build an instrument made up of separate components (or modules) that could individually alter the characteristics of sounds generated by oscillators. The revolutionary element of this first Buchla 100 series was a 16-stage sequencer, which represented the first opportunity to control the movement of electronic music without recording tones to tape and splicing them to achieve the desired rhythmic effect. Subotnick continued to be an influential force in Buchla’s work; his seminal Silver Apples Of The Moon album was created in 1967 on a Buchla unit which would be passed on to psychedelic folk singer Buffy Sainte-Marie for use on her album Illuminations.

Buchla was a significant presence in the 1960s counterculture, most infamously through his work with novelist and acidhead Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters. His Buchla Box was installed on the Pranksters’ converted school bus Further, immortalised in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test as the means by which the psychedelic troupe could broadcast their LSD-fuelled ramblings around the bus and to the bewildered passers-by of Middle America. Buchla also provided the sonic element of the Acid Tests and the seminal Trips Festival in San Francisco in 1966, as well as working as a sound man for The Grateful Dead. To pay the bills in between these more esoteric ventures, he also worked with NASA on various scientific projects.

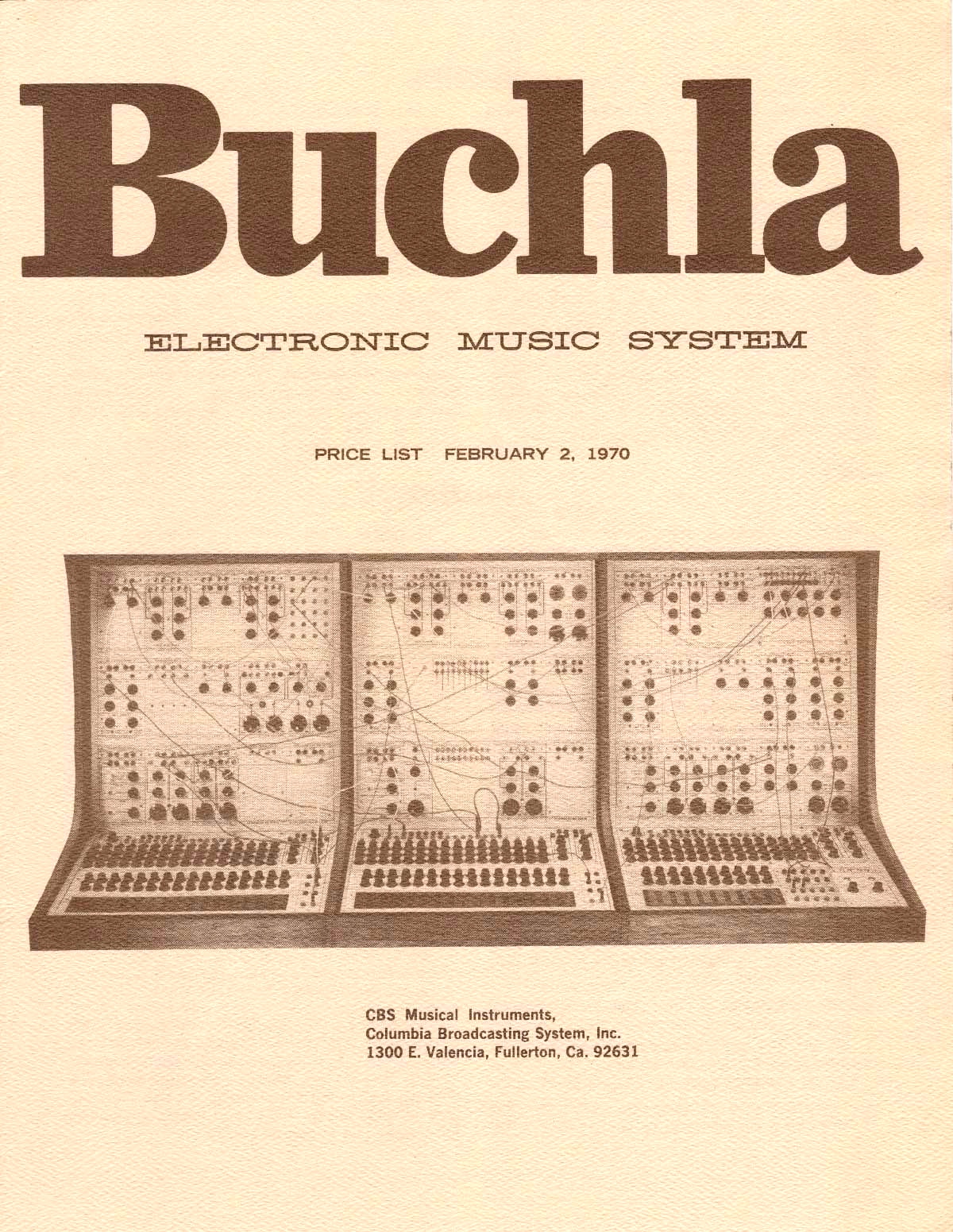

Through the ‘60s and ‘70s his synthesiser designs developed, with the iconic Buchla 200 series Electric Music Box in 1970 followed up by the digitally-controlled analogue Series 500. One of the most iconic of all his designs was the Music Easel, released in 1972 as a compact, portable version of the more cumbersome systems that had come before. Into the ‘80s, the synths continued to embrace new developments in technology, with the 400 Series incorporating a video display and 1987’s Buchla 700 featuring full MIDI integration.

For a time, Buchla moved away from synthesis and to explore MIDI controllers, developing unconventional devices such as the mallet-triggered Marimba Lumina. As the millennium passed he returned to his modular systems with the 200e in 2004, resurrecting the original ‘70s design of the 200 with modern benefits such as MIDI implementation and patch memory storage. As with the original designs, the modules contained within each unit were to be determined by the user, making each one unique to the requirements of the musician.

Buchla’s left-of-centre stance is mirrored in the music produced by his creations. Subotnick’s wild, alien sounds stood in stark opposition to the more commercially palatable Moog tones first introduced to a wider audience with Wendy Carlos’ Switched-On Bach. Over the years, fringe pioneers of synthesiser music such as Bob Ostertag, Pauline Oliveros and Silver Apples have championed Buchla instruments, while these days it’s apparent that artists looking for a specific type of feeling gravitate towards the ‘West Coast’ sound of the Buchlas. It might come as a shock to learn that deadmau5 is among those to have displayed his affection for the Buchla 200e, but we chose to speak to five artists who have developed a deep relationship with their own Buchla systems, some of them over careers that stretch right back to the ‘60s, as with early pioneers Suzanne Ciani and Morton Subotnick.

Alessandro Cortini, a longtime friend of Buchla, recorded his series of Forse albums for Important Records using the Music Easel. Anthony Child, on a sabbatical from his techno adventures as Surgeon, chose a Music Easel as his sole improvisational tool when recording the self-explanatory Electronic Recordings From Maui Jungle Vol.1, and Clemens Hourriere, in collaboration with Jonathan Fitoussi, recorded the excellent 2015 album Five Steps for Versatile Records using an original Buchla 200 at EMS Stockholm.

Morton Subotnick

“Don and I met in 1963, the year after I started the Tape Center with Ramon Sender. We put an ad in the paper to get an engineer to help us create a new approach to making music through electronics. At one point Don walked in. I thought he came to answer the ad but a few years ago when we were talking he said, ‘I didn’t really answer the ad, I came in to borrow a tape recorder.’ I gave him this whole speech about what I was looking for. Don said, ‘I can do that, I’ll bring it back tomorrow.’ So the next day he came in with this object that we had described, and it worked! It wasn’t very good, but it worked. He said, ‘This is not the way to do it though.’ For the better part of a year I worked closely with Don, maybe once a week, to conceptualise what became the 100.

“He didn’t know much about musical language, so when I got more familiar with the technology we could put together our two insignificant knowledges and communicate. I would say, ‘I think we need something that does X, Y, and Z,’ and he would look up into the sky and he wouldn’t answer my question for maybe 40 seconds. Then he would say, ‘I made that.’ To this day, he never explained it to me. I don’t know whether he was thinking, ‘Did I ever make something like that?’ Or was he actually figuring out how to make it, and then in those 40 seconds he made it in his head? I think it was the latter. That kind of enigmatic quality, it was very odd, but it was always that way.

“Both of our careers became public more or less in 1967 when Silver Apples… came out – our lives were joined so to speak. It was like a union of two completely different souls that together made what it is we both became, and we were both aware of that from whenever to the day he died.

“The 200e is poignant, because it connected us in a very direct way toward the end”Morton Subotnick

“After Silver Apples, when I was living in New York, we both got notoriety almost overnight and he was getting orders for the 100. I would get phone calls from people and they would say, ‘I wanted to buy equipment from Don Buchla but he won’t sell it to me,’ and he would tell them to call me. I figured that my role was to interview these people to see if they were okay for him to sell it to them.

“We stopped working together after the 200. The 200 had everything possible in it and it was great, and then he went on to these other things I really wasn’t interested in. We stayed close but I already had what I needed, but when he went back and did the 200e, he called me and he said, ‘I’d like to send one to you.’ I said, ‘I’m not sure.’ He didn’t articulate what it was – it was the 200 a million times better, and I’ve been using it ever since. We didn’t collaborate on it, he just did it, but it’s kind of poignant, because it connected us in a very direct way toward the end. Whenever we got together we could actually sit down and make patches and talk about them. He used them differently but I was interested in what he was doing suddenly, and he was certainly interested in what I was doing with it. It was a lovely coming back at the end.”

Suzanne Ciani

“I first met Don in about 1969. I was already looking for electronic music but I didn’t know that much about it yet. We went over to his studio at night and I was just was overwhelmed by this huge warehouse filled with electronic music modules. Don was a really odd person. Over the almost 50 years I’ve known him he metamorphosed. I went to work for him after graduate school and he was a man of few words. He used to make funny noises when he walked around. He sounded like R2D2.

“We had a rough beginning in a way, because I was in love with the concept of electronic music and I was completely dedicated to this new medium, and it wasn’t as if in a very warm way he took me under his wing. I did it in spite of him. He fired me the first day I worked for him.

“Don was a hybrid. He thought of himself as a musician, but his electronic designs were completely off the grid. When I was in New York and my Buchla 200 would break, nobody could fix it. I took it to the Audio Engineering Society and Don brought them the schematics. Nobody could understand those schematics. They were too unorthodox for conventional wisdom or training.

“It’s like having been in the presence of Da Vinci”Suzanne Ciani

“My second layer of life with Don Buchla happened when I moved back to California in 1992. My 200 series modular was broken, so Don told me to send it up to this fellow in Canada. It couldn’t be fixed, and so a museum in Canada got my Buchla, and I had no intention of going back to playing this thing.

“Don and I played tennis for 10 years in the ‘90s, and it was a lovely period because we healed a lot of the ancient wounds and we became friends. Then at one point he said to me, ‘Look, if you’re ever thinking about playing the Buchla again, now is the time because I’m about to sell the company.’ I wasn’t sure. The thing was traumatic for me. I dedicated 10 years of my life to playing this instrument, and then it would break, and I had had people saying, ‘You have to branch out to other things.’ It’s like being a violinist and being told you didn’t have a violin.

“I’m back playing Buchla again now. I can’t do the level of live performance that I could do then. Don had me convinced that this was a live performance instrument but it was extremely challenging to play it. There are a lot of details that make something performable. It’s a special subcategory, and I think Buchla of all modular designers cornered the vision of performability. He had a lot of feedback in the instrument. There are hundreds of LEDs in this thing and they’re all for a purpose.

“When I first met him he was, as I said, not very outgoing, and he became this warm, charming, loving man. I give great credit to his three wives. I think those women humanised him and I think that he travelled a long way. All I can say is that it’s like having been in the presence of Da Vinci.”

Alessandro Cortini

“I started becoming familiar with Don’s instruments going through photos and information in books. I felt this awe and attraction to just see what it was, as opposed to scientifically working out how to make sounds out of it. Around that time Don came back with the 200e series and I remember printing out the descriptions of every module, so when I didn’t have to teach I could just go through and learn what each module was doing.

“When I joined Nine Inch Nails in 2005, we filmed the video for ‘The Hand That Feeds’ and I wanted to utilise the 200e as a prop. A friend of ours let us borrow one, and I set it up for a shoot that was going to be two days in a row. After the first day I brought it home and said, ‘Fuck it. Let me just set it up and fuck around with it a little bit and then I’m gonna go to bed ‘cos we start filming again early tomorrow.’

It turns out I didn’t go to sleep. I just found myself completely engulfed in this machine in a way that I have never experienced before. When we went on that tour and hit the Bay Area, I got in touch with Don and he invited me over to the lab. I got off the BART Metro and walked the block, and couldn’t find his place until I heard these super fucked up weird noises coming from one place. There he was in the basement where he had a 200e set up with four speakers in each corner of the room. We hit it off pretty quickly and we just stayed in touch since then and eventually it developed into a cool friendship.

“Don was the most fearless person I’ve ever met in my life”Alessandro Cortini

“In 2007 I got my first Buchla system, and that was the beginning of a love affair with Don’s instruments. Unlike other designers, Don always designed his instruments for himself. The people that have the experience with Don’s creations and him as a person will say that the machines are totally him. They’re capable of giving things that you can’t get from anything else or anybody else. You develop a relationship with the instrument that is almost a human relationship.

“It’s the same for me with the Music Easel. I was able to find one after five or six years of searching. It didn’t work, and [modular synth designer] Mark Verbos spent a week at my place trying to bring it back to life. We discovered that it was actually the first Easel that Don ever built. Once it started working I set up my studio where it was the only thing between the speakers, and I just started writing stuff, and that stuff became three double records worth of music!

“The key word in Buchla’s instrument design is uncertainty. There is even a module called the ‘source of uncertainty’. This uncertainty is strictly connected to creativity and love for what you do, and it translates just like when they say you write a song from the heart, that people can feel it. Don was an incredibly unique human being, I think the most fearless person I’ve ever met in my life. It might sound harsh to say he didn’t give a shit, but in a non-negative way that’s exactly how he was, and it’s enviable. Now I have to continue that aspect of his life in mine, and try to be less of a scaredy cat!”

Anthony Child

“I think Buchla attracts weirder people, basically. My understanding is that Don Buchla was very much against building an instrument using conventional structures. He really wanted to break the mould, and that’s something that has always really appealed to me.

“A couple of years ago I saw a video of Charles Cohen performing with his Buchla Music Easel and it really blew me away. The main thing I thought was wow, that really looks like fun. I started looking into it and found that it was really hard to get hold of. I went to Berlin and they had a demo Music Easel in Schneidersladen. I played on it for 40 minutes and could barely get anything out of it, but something really attracted me to it so I ordered one and it took four or five months. I joke with friends about it – it’s almost like some kind of bizarre test. The Buchla has to want to come to you. You can’t just walk in a shop and order one.

“I felt like I was operating some kind of radio receiver picking up signals from distant galaxies”Anthony Child

“I absolutely love it. It’s such an amazing, deep instrument and really inspiring. I still feel like I’m just scratching the surface with it. I think that it’s designed in an unconventional way so it makes me approach it musically in an unconventional way. It has such a strong character, and you can’t force it to do something it doesn’t want, so I just try to let it run how it wants.

“The album I released in January this year, From Farthest Known Objects, I made entirely with the Buchla 200e system. That was weird because it was techno but there was something oddly different about it, and I think that that really upset people. That was part of the idea of it really, to make techno with machines that aren’t usually used to make techno. I felt more like I was operating some kind of radio receiver picking up signals from distant galaxies. These sounds seemed so bizarre and I couldn’t figure out where they were coming from. That’s where that whole idea for that album came from, somehow channeling these things that were out in the ether already.”

Clemens Hourriere

“I first came across a Buchla synth as an intern at IRCAM in Paris. It was like a discovery of treasure. I opened a box in the storage area downstairs and it was full of dust, and there was a Buchla. I suppose that this one was used by Morton Subotnick when he used to come to Paris to make some pieces of music.

“I was really into old synth stuff like the Moog modulars and EMS Synthi but never had the chance to touch a Buchla. Last year Jonathan [Fitoussi] and I said, ‘Okay, there is a Buchla at EMS in Stockholm, let’s go there for one week and have fun.’ Before the trip I did a lot of research about how it works because it’s quite different from all other brands. Jonathan missed his plane so I went there alone and started to play around and try to understand the thing, and it was a revelation. For me, it was the synth I waited my whole life for. It was a perfect match for my philosophy of sound, really inspiring and intuitive. Since then I can’t even touch another synth!

“The Buchla is really anti-keyboard players. I like it because I’m not a keyboard player!”Clemens Hourriere

“It was not our goal to come back with a record, but Jonathan and I played all day long with the synths and day after day we had new tracks. In the end we released an album from the sessions on Versatile, and it is 100 per cent Buchla. The name of the album is Five Steps because the sequencer has five steps, not eight or 16 or four, and that makes all the difference because you try things in different ways, not the usual 4/4 measure. I think the power of Buchla is this sequencer combined with all the organic percussive sounds, like wood or plastic tubes, that you can create. Also the keyboard is more a controller than a thing to play notes, so you can really modulate a lot of things with this keyboard – it’s really anti-keyboard players. I like it because I’m not a keyboard player!”