Pioneering feminist icon Viv Albertine of The Slits has a long history of musical disruption and her latest memoir, To Throw Away Unopened, which details the exhausted reality of middle age, is a vital and unique addition to the punk canon. Claire Lobenfeld talks to Albertine about writing, female discontent and “nice women”.

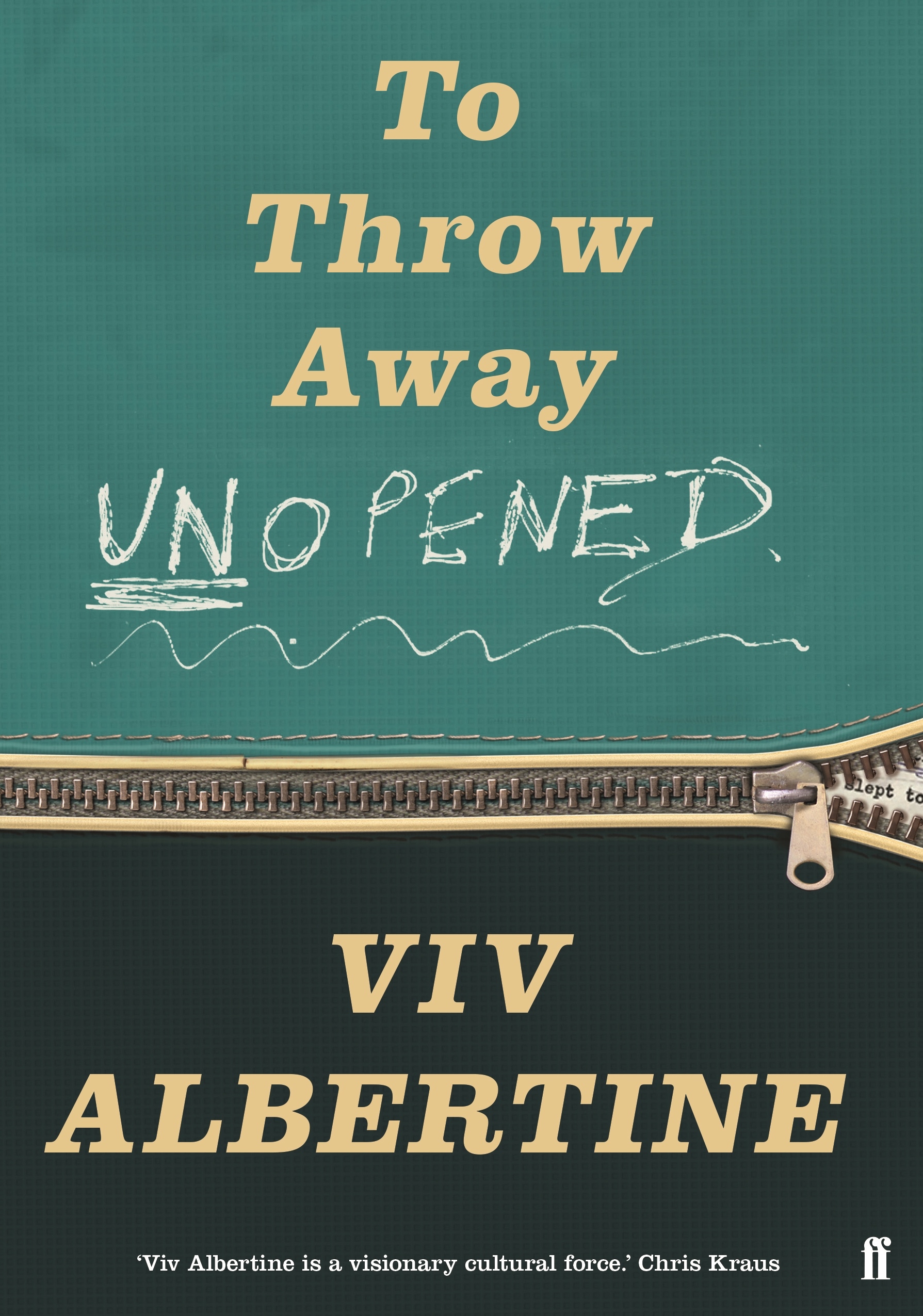

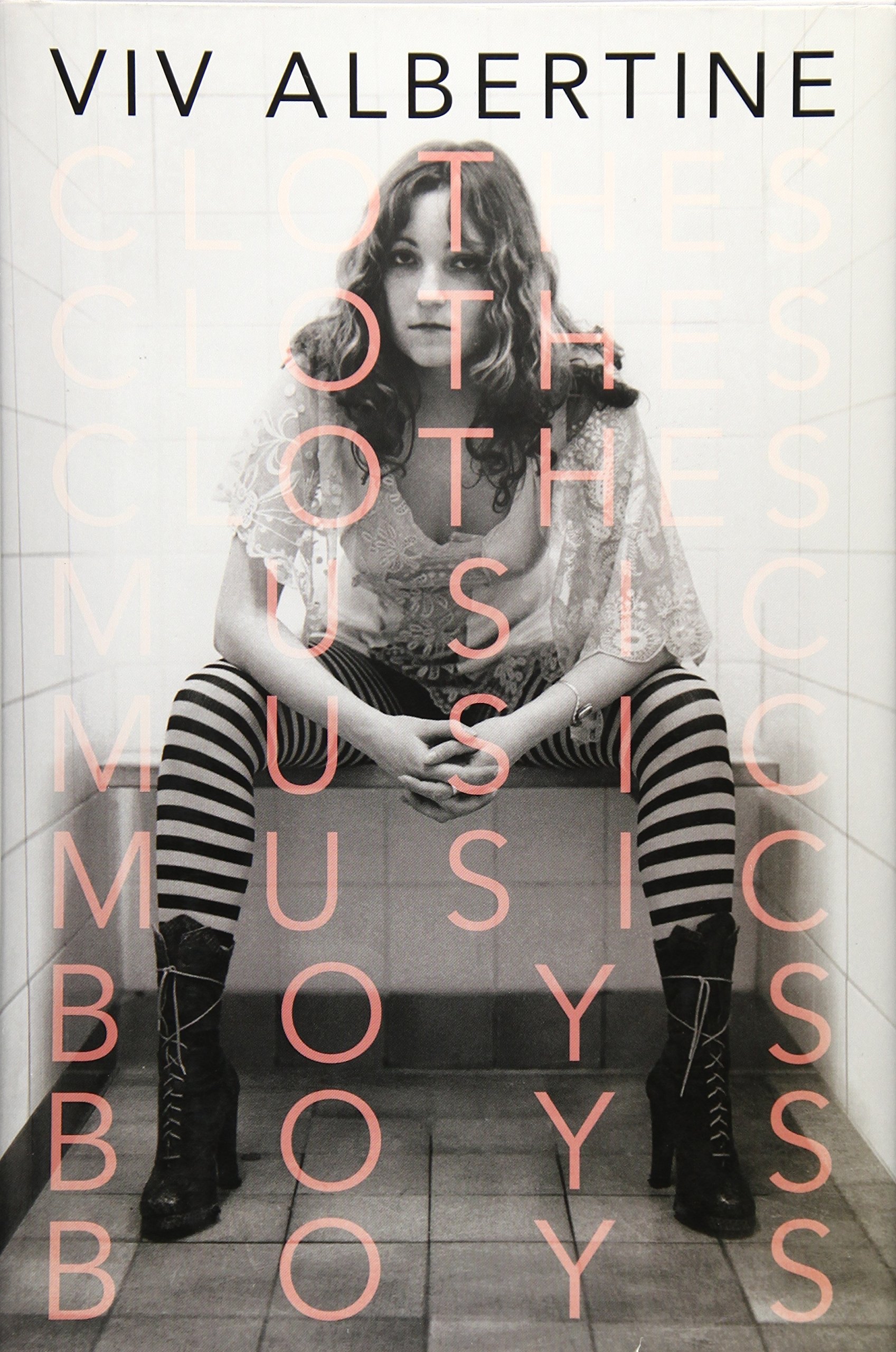

Can format be feminist? Viv Albertine, author and a founding member of the legendary punk band The Slits, has figured out that it can be. In both of her memoirs, 2014’s Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (an essential of music history), and her latest, an autobiography about childhood, sisterhood, and motherhood called To Throw Away Unopened, she punctuates her own text with quotes and ideas she’s collected from other writers and thinkers.

When we speak about the quotes, which are almost like epigraphs for each part of the book, she says that accreditation is a form of feminism: sharing that fact that you’ve learned something from other women by making known how their intellectual work has impacted your own. It’s also how I walked away from our phone call with some of the best book recommendations I’ve ever gotten from another person. Aside from her own work, Albertine and I chatted about working between cerebral and visual disciplines and how periods — the menstrual kind, not the punctuation — can be powerful.

I guess you started from doing more visual work in a lot of ways. How did that transition work for you?

Viv Albertine: “As I was writing the first book, I tried to see the scene because I didn’t really know how to approach it because I hadn’t written a book before. I wrote it almost like I might write a script, but whatever path you take, it will all inform the writing really. That’s the great thing about writing: you could work in a store, and be a mother, and have done a bit of traveling, and all that informs you as a writer. I think you can bring everything to writing really. It’s just that my particular disciplines — art school, film school, being in a band — make me a certain kind of writer.”

“I was determined not to be someone just churning out work for the sake of it”

How did you start with this book? I read an interview where you said something like you didn’t want to write another book, but you felt like writing needed you. Can you tell me a little more about that?

“It’s more that I needed the writing. I needed to be needed. For three or four years, every day I had to put a few hours work into the book. And when it was handed in, and I’d gotten over the shock of someone else reading it and all that, as the months went by, I missed something like that needing attention. My daughter was going out on her own, you know, and hadn’t got a proper job, so that’s what sort of led me to write another book. Before that I was determined not to be someone just churning out work for the sake of it, not for the sake of money or commercialism, but to fill my heart and my days.”

One of the things that I love about your books is how they’re punctuated with quotes from other people. It really informs the text of this one. Early on, I kept thinking about how Maggie Nelson did something similar in The Argonauts and within just a few pages of this book, you have a quote of hers. What inspired the choice to have so many words from others?

“I love quotes. I do slightly collect them and as I’m writing, I find that they find me in a way. I think it brings a real richness. One of the threads running through the book is an acknowledgement of other women writers and thinkers. Sometimes I’ll quote my mother or my friend in just the same way. A lot of female history and experience is passed on orally. I wanted to isolate the quotes so you actually have to take notice of them. I’ve wanted to make sure that I gave credence and credit to people, whether it be a friend or a mother or a great writer and not take the credit myself for having the thought. And it’s so tempting to rewrite it or pretend you thought of it or pretend you didn’t read it in a book somewhere and paraphrase it.

“So, I always, always credited where I got a thought from or even when someone had passed a book to me that I got the thought from. I was sort of a political act, in a way, to credit people who’d led me to things, to credit the people who’d made interesting observations or had thoughts before me that I’d embroidered into my own work. That was a very conscious thing and it’s a thread running through the book which, I think, is insistently but quietly feminist.”

There’s that adage about how writers are always stealing from somebody else, but I think that it is memoir in its own way to say, here are quotes that I think of, that inspire me, like you’re detailing your process for us, which is a sort of meta-memoir within the text.

“It didn’t occur to me probably until about a year in to acknowledge the people whose books I read that led me to another writer that and so on. I’m really glad I did it, but it wasn’t always easy to do. My ego did fight it a little bit.”

One of my favorite ones that you used is from Violette Leduc: “Children remember things without understanding them. They are oceans of goodwill drinking in an ocean of words.” How did you come across that one?

“The first really striking memoir I’ve ever read is by her. She wrote La Bâtarde in the ’60s. She writes like a punk rocker: absolutely in your face, unapologetic. It was about sex and her bad feelings. It was way ahead of its time. We’ll watch something like Curb Your Enthusiasm or a show like that where the character’s quite bad and we laugh because we recognize ourselves in that bad character like Larry David. But she was like that way before Larry David. I don’t know why that book it hasn’t caught on because it’s so way ahead of its time.

“Someone like Valerie Solanas did that as well, but we were so busy being shocked and frightened and outraged by what she was saying. There’s a lot of humor in her writing and a lot of acknowledgement of her rage. She wasn’t pretending to be a nice woman. Many of the women I quote are not pretending to be nice women. I noticed when I was a director that male directors never smiled, gave their directions with a very straight face, really quite harsh face and I’m like beaming and showing all my bloody teeth. Violette Leduc was one of the first women I read who admitted to not being that kind of a fraud. And it was utterly liberating.”

Women’s anger or women’s discontent seems like the last taboo to break. Right now, it’s pretty common for women to very totally open about sexuality, which is great, but you’re still making yourself available to for other people’s pleasure. It’s not coming to terms with your own anger. I get mad about stuff all the time.

“You say, ‘I get mad about stuff’, but it’s sort of slightly apologetic. Why? When I was growing up, to be an angry girl was to be two terrible, terrible things: unattractive and unfeminine. These were the biggest sins any woman could ever commit. It’s really only in the last couple of years, and I’ve been so thrilled to see it, that women talk about their anger and their rage, because up until a few years ago, most people hid. But, you know, if you’re an angry young man, you’re cool, you’re sexy, you’re deep.”

There’s still nonsense about women’s anger related to being on your period, too…

“The anger one has when one has a period, for instance, is a huge energy that can be harnessed. It’s also a clarity: the bullshit drops from your eyes in that state. So, you start being put down and told you’re vulnerable, but really, you just don’t want to play the game. And that’s threatening to a lot of people, especially people who are still advancing patriarchy.”

Earlier we were talking about archiving the intellectual work of other people in your book. A lot of punk feminism has been archived over the past few years: there was a book about The Raincoats last year, Kathleen Hanna has her archive at NYU, your first memoir and there’s new documentary about The Slits that’s just come out. You also brought up women’s oral tradition of sharing our history. I’m curious if you’ve thought at all about how we can continue to build a history of women in punk.

“There’s something very fighting happening with women writing non-fiction and telling stories, whether it be Maggie Nelson, Rebecca Solnit, Alison Bechdel and it’s incredibly creative and formally interesting. I just think it’s going to continue to happen with women in music, too, like it has with Kim Gordon and Chrissie Hynde. I think we’re sort of eclipsing other kinds of, dare I say it, male writing at the moment. There’s a history of it, too, whether it be Virginia Woolf or Violette Leduc or Anaïs Nin.”

It’s funny, l just mentioned something about how women are starting to be unapologetically upfront about their sexuality and you’ve just mentioned Anaïs Nin who doing that in the 1960s….

“I can’t believe she got away with it. It was mostly because she was writing, she was hanging out with such sort of liberal artistic circles, wasn’t she? But, I wouldn’t be surprised if the people around her were quite dismissive of her and put her down. I think she was probably being put down for being sexually promiscuous. All I know is that I absolutely devoured her diaries when I was young. And I loved the pace of them, they’re very rhythmic; a bit like boxing compared to an action movie. I just got into the pace of it and got really, really deep and quite addicted. It’s such confident writing.”

Claire Lobenfeld is FACT’s Managing Editor. Her brain broke when she found out The Slits’ ‘Instant Hit’ was about Sid Vicious.

Read next: Post-punks Algiers tackle political unrest on American and British soil on The Underside of Power