A former geotechnical engineer from Colombia currently based in Berlin, Lucrecia Dalt has a unique approach to electronic music. Since 2005, she has challenged the rigidities of form, experimenting with South American rhythms, unusual vocal phrasing and innovative electronic techniques. Steph Kretowicz digs deeper into Dalt’s relationship with geology and musical experimentation.

“I thought this is kind of cool because it’s a really strange position to be at,” says Lucrecia Dalt, about first becoming acquainted with abstract subterranean space in the wild formations and complex strata of Latin America. “We were slowly getting a sense of everything that was underground, just by digging, every other week, and every other month, and every other year, to the point that we were getting a sense of this huge mass of earth beneath us.”

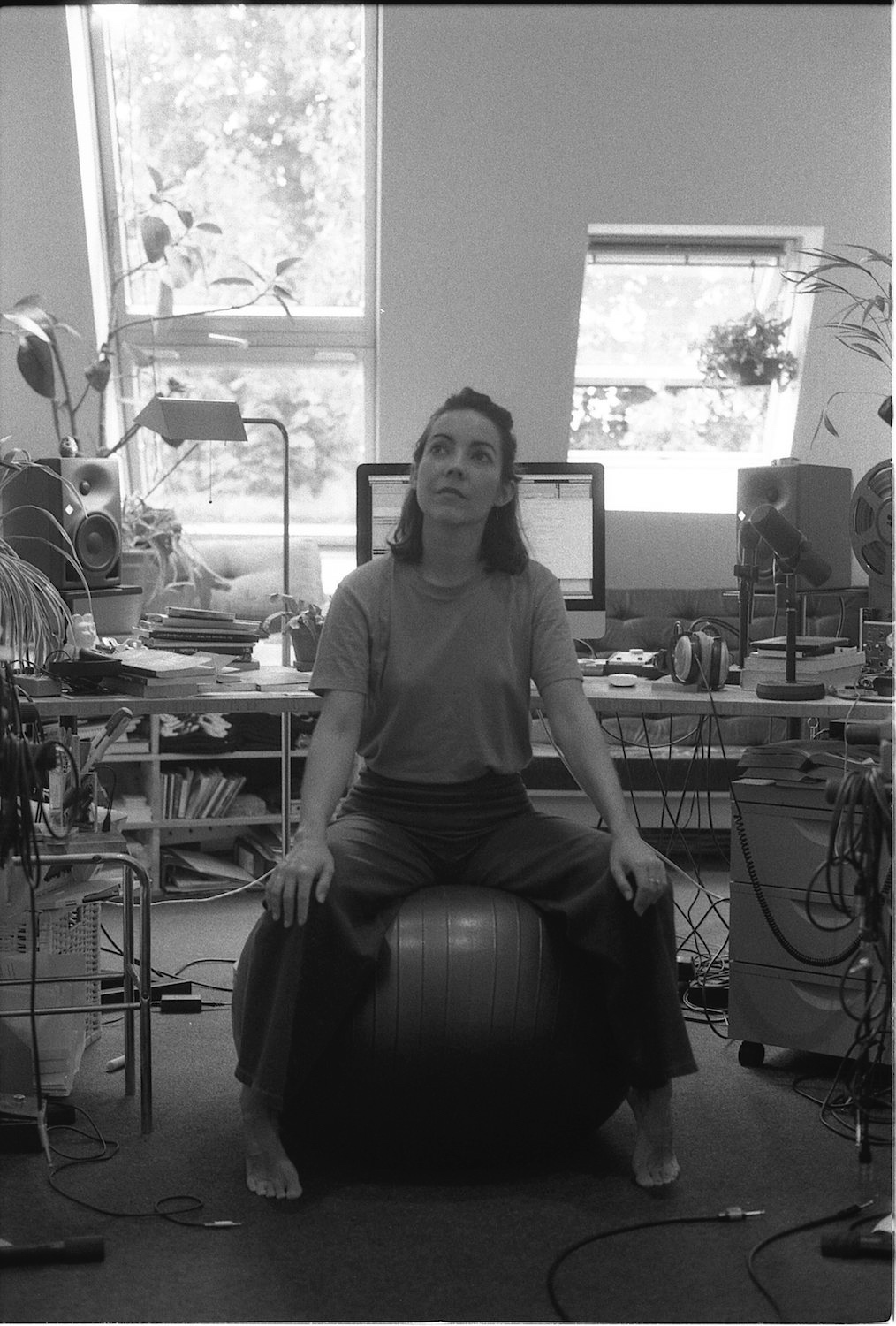

Speaking from her current base in Berlin, the Colombian producer appears on-screen flanked by gear: a stand, some books, cables, guitar, a speaker with a model brain on it. She’s talking about her latest album, Anticlines, and the memory of a past life that inspired it. “I found this form that sort of explained visually this phenomenon,” she says about the titular arched fold of stratified rock that brings the oldest earth into its core and to the surface. “What is at the bottom has the opportunity to reshape the present, let’s say, or a certain specific present. Then it seems as if we have to think about time not in this linear way, and I like that.”

The outcome is a soothing and cavernous sound that moves at a sloth-like pace. Tracks with names like ‘Tar’ and ‘Edge’ contemplate notions of consciousness and subjectivity through highly allusive fragments of poems compiled in a collaborative lyrics book by Dalt with artists Regina de Miguel and Henry Andersen. Dylan Trigg’s book on the limits of human experience, The Thing, sits alongside a mythical Amazonian monster – El Boraro – which crushes its prey and sucks the skin dry. Minimal and microtonal compositions give space to subtle textures that echo the traditional rhythms from Dalt’s distant childhood. They’re buried in a dense combination of ideas and speculations, forming the deeply seductive sonic landform of Anticlines.

I keep trying to apply what I already know about geology to your work, to which you seem surprised I’ve arrived at those conclusions. It’s like I’m trying desperately to understand your thinking and the music but not succeeding.

Lucretia Dalt: [Laughs] I’ve been thinking about that. Throughout the interviews I’ve been doing, I realized that in the end we’re talking about music – or what I’m presenting is a work of music – but I really cannot avoid to put all the information that I gather, or that I put together for this behind it. I give equal importance to that. For this record, it came strongly. Maybe it’s because of the work that I’ve been doing with Regina or the interest in reading this kind of critical theory. I’ve started to think that maybe the memories I have as an engineer are resonating more strongly with me right now.

I tried to think about time in music. How can I create a structure that sort of suggests that something is moving, that it could be bringing something from the past and disrupting the present? But then, it’s totally fluid, in a sense, and this is how geology is.

It’s also about consciousness. You almost never think about the underground and what is lying beneath you; what it means and if it could be telling certain stories and how it shapes everything – economies and things like that. To have this idea that this possibility could change your human scale, you stop thinking about your edges and your relationships and you move to something bigger. I just liked it as a metaphor to work with.

I’m living in California at the moment and it’s strange being in a space that is so volatile, geologically, where there’s this palpable, low dread that the ‘Big One’ is going to happen. Living in that environment, you’re so conscious of it.

Dalt: Yeah, that’s right. I think about it a lot because in Colombia, for example, they haven’t been able to make a highway between South America and Central America, just because the area there is just impossible. There’s this huge mass, or kilometres of marshes and I remember, as an engineer, we had a project there to check again if there was any possible way to build something there. Economically it would be crazy because how are you going to do that? Then again, is it worth it to? Why is there a necessity to do this anyway? I don’t know.

How do these ideas translate practically to the music itself. Do you create the music and then these abstract concepts come up? I’m interested in how it shifts the sonic elements themselves.

Dalt: It’s just an environment for me to start working. I don’t have band mates and then you stop working out of epiphanies or trial and error – because I got tired of those processes, just waiting for an idea to come or just improvising endlessly without having anything to relate to. I thought that the only way that I could get something a little bit more concrete, and specific, and more like that it has consistency, was to have all these environments and all these ideas that are just in my head. This is probably reflected but maybe not directly. I’m not making questions. I’m not making something very direct, like how can I make this sound like rocks?

I don’t make that connection, but the information is there and it invades the music production. This is what I like but I’m not sure if the music would have been the same without this, probably not. If I just started to work out of nothing. Especially with the lyrics, when I hadn’t written them already, they just suggest already a kind of rhythm or something. When we wrote ‘Edge’, for example, I was like, “This has to be something very pulsing and confronting.” I like this kind of dry and direct word that’s telling you a comment or something along those lines.

When you talk about this visual representation of non-linear time and consciousness with the anticline formations, it’s interesting that the record feels very much like a quiet depiction of “consciousness”. That’s why the real stand out, in terms of themes, is the mythological one based on El Boraro, Errors of Skin. It goes even further into some kind of collective, or primeval thought.

Dalt: There are certain images that I have, which I can move and everything sort of makes sense. A simple one is the idea of an axis. You put an axis on it, and then you could start at the level of the skin and, of course, you have to end up in some sort of geology, and then you end up in the confinements of the solar system. Then I was trying to think about, as you say, “consciousness”. Where is consciousness happening? I was reading Dylan Trigg and he is questioning what is the human body all the time, whether we can think about a phenomenology outside of the human body. He resolves that with horror, which is quite interesting.

I was also thinking because of my ideas of geology that the things that he talks about – of this bacteria found in the Antarctic that could suggest that maybe life was actually coming from Mars – are quite interesting to me. As to suggest that maybe we are so centered on the human body and [the idea] that consciousness is only possible on it. But then whenever you cut through it there is so much history there that could be suggesting another kind of consciousness.

Then to bring it to this extreme, can you think about love in the heliopause [laughs], does it make sense at all? I was trying to move the scale and move the point of view, all the time. This is what I wanted to play with, so ‘Edge’ is an extreme take on love and eroticism, in this way. I want to preserve the other from within but from another kind of whole, and then it’s just removing the insides, and then playing with this space of perception. Is it my consciousness mixed with yours or is my subjectivity mixed with yours, is it possible? I was trying to think about what I was reading and using this myth to put it all together and make sense of it, or not make sense at all but make a poem out of it and work with this metaphor.

Is that a brain on your speaker?

Dalt: Oh yeah [laughs]. That is a brain. Well, in looking for a consciousness, I got into this idea of the brain and then I thought about this consciousness-type brain that manifests. When you think about consciousness, maybe the most direct thing would be to link it to the brain, or is it is on the periphery, or what is it? I used it at CTM [Festival] as an object on stage because I was thinking if I could have some sort of tension in another object that is outside of my instruments and stuff like that. I’d been taking classes with this performer who made me think about my own body, and the way I look, and where I come from because this is something that also interests me, especially now with these lyrics. I wanted to make this sort of alienated lecture that is between a lecture because it seems like I’m talking about a specific subject but not because it’s alienated by a music concert.

Then I was like, “How can I distract or redirect the attention of people by looking at something?” So, of course, when I start to look to the left multiple times, probably you’re going to look somewhere else and try to figure out what concerns me there. These are little strategies on what I was thinking about how to work with performativity. It’s not the usual boring man looking at the machine and just tweaking stuff. I was thinking, “How can I be as a body there a bit more active, and not just giving commands to my machine?”

Anticlines is out now on RVNG.

Steph Kretowicz is on Twitter.

Read next: Feminist punk icon Viv Albertine on liberation, women’s anger and the value of writing