Cecil Bustamente Campbell, better known as Prince Buster, died on September 8 from heart problems following a series of strokes. He left behind a legacy that changed the course of Jamaican music, pioneering the ska sound and taking it across the globe. David Katz remembers a true original who recorded with Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, befriended Muhammad Ali and inspired generations of ska lovers.

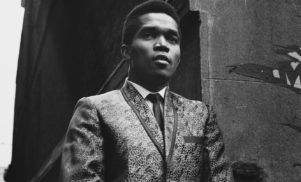

The death of Prince Buster at the age of 78 marks the end of the line for a true Jamaican original. The man who invented ska almost singlehandedly was laid low by a stroke in 2009, the only obstacle that could possibly stop him from delivering his intense live performances on the world stage. Despite growing up in the hard-knocks environment of downtown Kingston, the Prince retained an air of youth all the way into his seventies, still possessing a full shock of wavy black hair and the strength of a man decades younger.

Live gigs at international festivals continued to be well-received, the Prince just as comfortable with a group of Jamaican expatriates like the Junction Band behind him or a Japanese ska revival unit like the Determinations, such was his general adaptability, and the continued veneration by a legion of fans worldwide ensured that overseas backing bands were always well-versed with his huge catalogue.

Buster’s wife, Mola, told me that the stroke had confined him to a wheelchair and affected his speech, yet he responded well to initial courses of physiotherapy; doctors advised that things could go either way and everyone was hopeful of a full recovery. Sadly, things worsened for the Prince with the passing of time. He died on September 8, 2016.

I first met Prince Buster in 1999 at an album launch held in a posh venue in Camden. I was then working on People Funny Boy, the authorized biography of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, and the mention of Perry’s name made Buster’s face light up. We arranged to meet a few days later for a formal interview and Buster regaled me with tales of rescuing Perry from a knockout punch delivered by Duke Reid’s henchman at a Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat sound system dance in Kingston during the early 1960s.

Buster was equally renowned for his boxing talents and Perry’s short stature made him an easy target, which is why Buster took it upon himself to come to the rescue, even though he’d already broken away from Coxsone to form his own Voice of the People sound system. Buster and Perry later collaborated on some impressive work in the rocksteady era, notably on the hit ‘Judge Dread’, one of the first songs to address the corrosive phenomenon of ‘rude boy’ street gangs.

In the new millennium, during our subsequent meetings (most of which took place in south London, where Buster retained strong links), the Prince filled me in on the particulars of his lived experience and the ups and downs of the Jamaican music industry. He pointed to the strict Christian upbringing that dominated his household as the defining element of his founding principles, and was fiercely proud to have been the only record producer in the early stages of Jamaican popular music to have been born and raised in the heart of downtown Kingston. As he said, “Duke Reid come from Port Antonio, Coxsone come from St Thomas, but I am the only one who born and grow on Orange Street, right there at west Kingston.”

Buster began his singing career at the tender age of seven, when he regularly performed in a local nightclub. He was brought into the boxing ring by former Jamaican middleweight champion Speedy Baker, though it was the sound system deejay Count Machuki who helped him to perfect his right hook. Boxing and music were twin passions in his youth, and meeting him in person, his toughness was readily apparent; tucking into a plate of steak and chips at a Streatham boozer, there was something of a Mike Tyson quality to him; he retained the aura of his Orange Street upbringing despite having lived in a tranquil Miami suburb for many years.

At one point, to illustrate more fully the excesses of sound system battles waged in Kingston during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Buster took my fingers and traced them along the back of his skull to reveal a severe indentation, the result of a violent attack launched by Duke Reid and company at Chocomo Lawn. If anything, Buster was certainly a survivor, as described in his autobiographical hit, ‘Hard Man Fi Dead’.

Buster will always be remembered for the ska he produced in the early 1960s, with hits like ‘Wash Wash’, ‘Madness’ and ‘Al Capone’ making him a mod icon, but he had little recollection of the mod movement. What he retained from his pioneering tours of Britain in the early 1960s was a sense of veneration by the teddy boys, who, despite their reputation for racism, apparently followed him far and wide, becoming unofficial bouncers at his club engagements.

Buster was also keen to give kudos to Emil Shalit, the enigmatic founder of Melodisc Records who became Buster’s manager and facilitated his breakthrough in Britain. Accounts of Shalit have not often been flattering, with the general suggestion being that selling records was akin to selling potatoes for the man, but Buster painted an entirely different picture.

“Mr Shalit is a very wise man who know some 10-plus languages,” he told me. “He is a man who was an intelligence officer in the United States Army, who jump out of airplanes in Germany, so he is a very wise man, and I credit him. What I had at the time was a sort of village concept of things, and Mr Shalit internationalised my mind.”

Buster was also proud of his enduring friendship with his boxing idol, Muhammad Ali, and noted that Ali’s membership of the Nation of Islam prompted him to convert to the faith in the early 1960s; he remained an active NOI member for the rest of his life. However, the mosque he opened in downtown Kingston displeased the Jamaican government, and the pressure they exerted on him ultimately prompted his move to Miami. After releasing some early dub and deejay records, he was largely absent from the scene by the mid-1970s, but the 2 Tone ska revival brought him back onto the stage after Madness paid tribute to him in song and the Specials and the Beat adapted his work.

Looking back on his career, Prince Buster showed humility in hindsight, acknowledging the mistakes of his youth and the ‘empty glory’ of sound system rivalry. He ultimately remained pragmatic and philosophical about his life’s work, seeing his music as part of a greater spiritual battle to motivate humanity to do good. The last time we spoke, he explained it thus: “Shakespeare said, ‘He who strikes the first blow soon admits he has lost the argument.’ That’s why I strive hard to be who I am, and if them don’t defeat me up till now, then I got some powerful force on my side. Me just ah battle them minds now, and since I mean good, I think I’m bound to win.”