Signal Path is a series that delves into the creative process of our favorite producers and musicians. In this interview, Maya-Roisin Slater meets techno icon Richie Hawtin, who reveals how he made his first tracks as F.U.S.E., 25 years on from the release of his first album, Dimension Intrusion.

“At this point techno was faceless, it was the nerd’s music,” says Richie Hawtin of the late ’80s and early ’90s when he was getting involved in electronic music. “I was just happy to be in the corner of the DJ booth playing where nobody was watching because everybody was dancing. Or making music by myself in the basement under my parents’ kitchen and sending records out to the rest of the world.” We’re sitting on the corner couch of his cushy Berlin studio, a pair of felt slippers lie strewn on the floor, and a Sheet One mug containing an old bag of sencha green tea is positioned on the monitor’s right-hand side amidst a daunting collection of gear.

Now widely recognized as one of the defining figures in acid techno, Hawtin started out DJing in his hometown of Windsor, Ontario, a modest city in eastern Canada, just over the border from techno’s birthplace, Detroit. “I started going to Detroit as soon as I could when I was 15. I would go resale shopping because I didn’t like the designs at Le Château anymore,” he laughs.

As he grew older and got more interested in DJing, those trips became more of a pilgrimage. “You couldn’t be into the scene or getting into it and not understand that the music that was being made was kind of a revolution that was happening around the world,” he explains.

“My favorite records were being made by people 10 miles down the street in Detroit. Then as you start going out you start brushing up against these guys a little bit and seeing they’re kind of normal. Well, they were crazy and charismatic, but it wasn’t like a rock star or Prince, you could talk to them.”

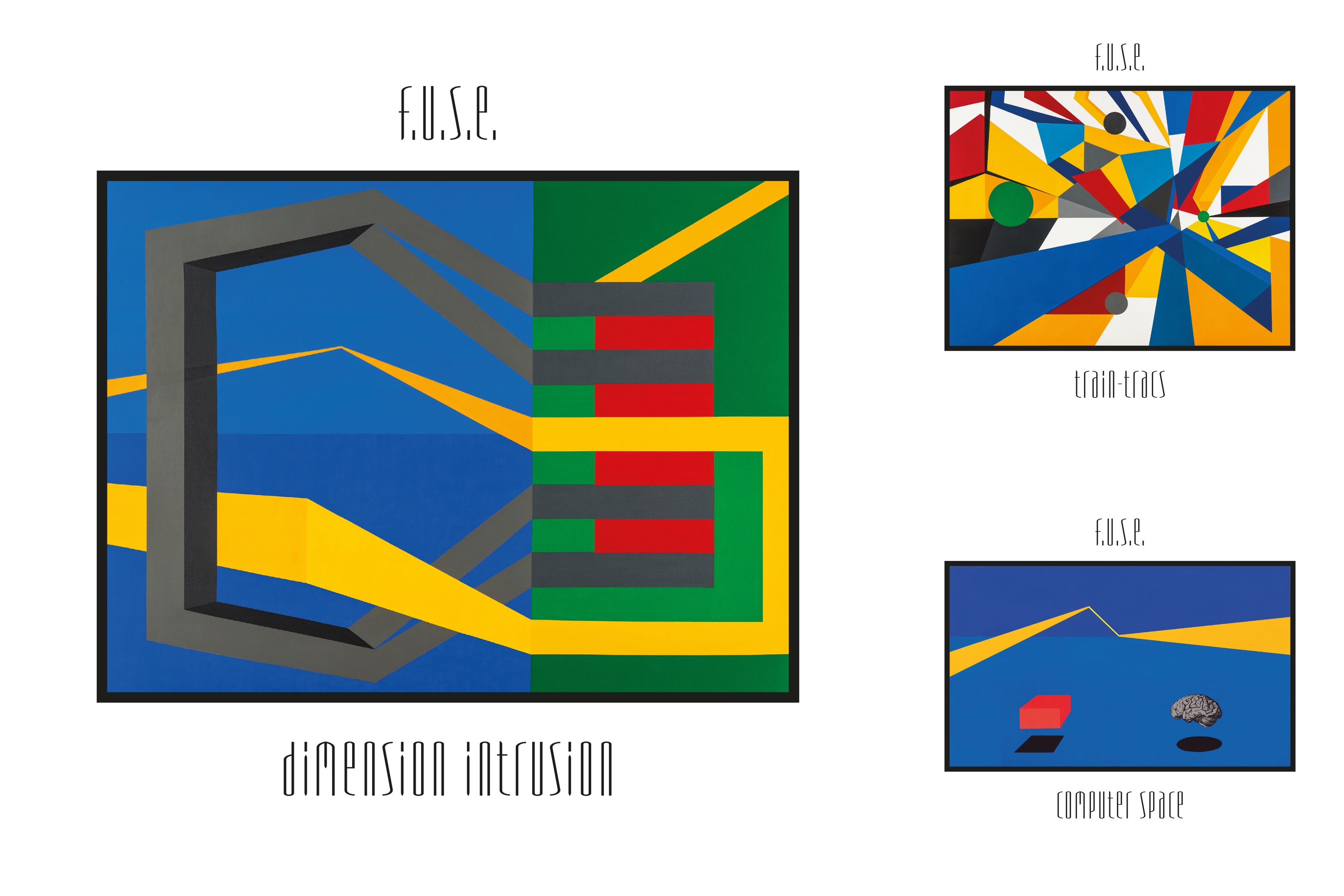

This creative atmosphere encouraged Hawtin to start tinkering with music himself, combining the nearby futuristic sounds of Detroit techno with Chicago’s acid house scene and the spectral frequencies of the sci-fi movies he obsessed over as he grew up. These initial tracks would eventually, with some glueing together, become his first album under the alias F.U.S.E., Dimension Intrusion. Laying the groundwork for what would become Plastikman, the F.U.S.E. sessions spawned two more albums: Train-Tracs and the previously unheard Computer Space, which was finally released alongside the other F.U.S.E. LPs as part of a retrospective box set through The Vinyl Factory last month.

When you were making the F.U.S.E. albums, you were working out of your U.T.K studio in Windsor. What did it look like in there?

Richie Hawtin: It was my first real studio. It was a storage room under [my parents’] kitchen, which was why the studio was called U.T.K, Under The Kitchen. You had one wall full of all the analog synthesizers, a little corner that had my Atari computer, which I used for strings but nothing else really, and there was a wall in front with my Tannoy speakers and a world map, which I started putting pins in as I started traveling. And I think a Metropolis movie poster, a couple of movie posters, all sci-fi, then on one wall faxes of orders that were coming in from my record label at the time, and another little piece of wall that was full of tapes. What I would be doing back then is dumping what I was working on onto cassette so I could listen to it in the car. In the other room was a reel-to-reel where I was doing my editing and tape slicing. It was pre-hard drive for me because I couldn’t afford one so everything was still on cassette. I was mastering onto a DAT but to listen and to take to other people’s houses you were listening on cassette.

For a young producer nowadays there’s FL Studio or cracked versions of Ableton Live that provide barrier-free access to making music. But for an electronic artist in the ’90s affording gear was an issue. How did you go about collecting the tools you used to make the F.U.S.E. albums?

RH: Part of my sound and search for my sound came from the pieces of equipment that I could find and that I could afford. After ’93 the F.U.S.E. album came out, and I was DJing more. Then I was able to take my DJ income – never my music income [laughs] – but my DJ income to buy a $2,000 modular keyboard which now would cost $20,000. But back then everything was made with stuff that cost 50 to 100 bucks. Like my [TB-]303, I found it at a pawn shop. Back then I was working at a video store to make some money, I was DJing a little bit, and if I wasn’t there, I was usually travelling around Detroit between record shops and pawn shops. We’d go to music shops to look at what we’d maybe one day be able to afford, but mostly it was [Roland] 909s, 808s, 303s, 101s – everything was bought at a pawn shop.

Over the years I’ve been able to afford other synthesizers I won’t namecheck that I couldn’t afford back then. But when I try to make productions now with them, they just don’t fit. Like when I go to a [SH-]101 or many of those old Roland devices I can put one two and three things together, and it may not be the best track in the world, but quickly it will gel together. And when I put instruments quickly into something now that I didn’t use back then I have to spend much more time to make it work. So the luck of what I found at those pawn shops back then was what either helped me mold – or molded – my sound into the only thing it could be.

You’ve said in making Dimension Intrusion you wanted to find something in-between the futurism of Detroit techno and the hypnosis of Chicago house. How did you go about building that aesthetic?

RH: The futurism in Detroit really boiled down to the 909 drum machine for me, especially the claps, the hi-hats – particularly when you brought the metallic mid-range up in those, they just had this kind of rhythm that was such a beautiful forward momentum. Nearly like pushing yourself into the future. The 303 on the other hand, I love the squelchy-ness. I liked that it was sucking you in, but I didn’t like so much when it got too hard and grating.

I think one of the things that enabled me to fuse those two things together was using very syncopated 16-note drum patterns on the 909 and oftentimes three or five-note polyrhythms on the 303. So that even as you were feeling the structure of the track and the normal four-bar eight-bar changes over top, there was this other melody and squelch and delayed line that never seemed to have a beginning or end. Those were the two things that came together that really made ‘FU’, made ‘Substance Abuse’. All over Train-Tracs, there’s always some kind of melody that’s looping in a different time signature.

What did your recording process look like? Were you writing things out before or was everything improvisational?

RH: Everything was improvisational. I think I’ve maybe released one or two tracks in my whole career that were arranged on a computer. I would usually start with some kind of rhythmic bassline or sound with a 101 or a Pro-One. I used to go to those because they have very simple but elegant sequencers built into them, where you add your notes and then trigger them from the 909 or 808. What that allows you to do is very quickly find a series of notes that you like, but then work with a drum machine interface and then move the placements of the notes around. And what was also great about that was that as you’re programming drums and maybe three or four different bar variations you could change trigger points so that the melody is still there, but the melody is just playing in slight variations.

The 909 would be my master control. It has 16 patterns and some banks, but what I would end up doing is having a bank of 16 one-bar loops that would contain drum information and timing information for all the other instruments, one trigger point or a couple more on the 808 for basslines. And then usually I would actually take a MIDI cable out of that going into an old Akai S950 sampler, which would also allow me to use a drum like a tom as a MIDI trigger for a sample like a voice or something else. So what also came out of that is those tracks have a very nice feeling on a timing level, which I think comes from the timing of the 909 drum machine. I’d be sitting at the 909, triggering sequencers, adding melodic triggers then adding hi-hats, maybe from some other drum machines.

Once that was all going I would copy that pattern, make variations on all the drum machines, and then once it was ready I would have everything separated. I had a 16-channel Allen & Heath GS2 mixer, which was very important because it had a lot of sends for effects and it had a really great EQ. So everything would be on a separate channel, and as I was creating the song I would actually be mixing it already. By the time the song had a good feeling and everything was programmed, the mix of the song was done also. Then I would mute everything, make my variations, press start with a kick and start bringing things in and jumping between different patterns on the 909 to find a good live arrangement. I would usually jam with it for a couple of hours while I was making it, so I had an idea of “OK, I want to start this with a kick and a bassline”. Then I’d mute everything and leave that up, press start, do eight bars and then bring in a hi-hat and kind of feel my way through it.

How did sci-fi inspire the F.U.S.E. records?

RH: When I wasn’t in the studio and I wasn’t out I would be watching Logan’s Run or THX 1138 or Forbidden Planet for the 20th time and those movies and soundtracks, they were just these environments. Being in my studio and sometimes letting everything bubble, it would happen that I’d be recording and have an hour of tones and delays at the end and be like “what am I going to do with that?”

Going into the studio every day you just followed how you were feeling. You were experimenting, you weren’t always making a slamming techno track every day – that’s what the F.U.S.E. album was about. At that point in techno music, most of the albums that were coming out were compilations of all your hardest hitting dance floor material. Growing up with Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream and Pink Floyd I knew that there was a greater potential, like just listening to 4/4 on an album was not going to make me happy – there had to be something there, a story or something that was deeper or more immersive or trippy. More like a soundtrack. Because part of watching those sci-fi movies is just the sonic trip you’re on. Some of that was talking, but Forbidden Planet, THX 1138, Logan’s Run, the music and the atmosphere that’s involved on just those three alone – I wanted to create something like that. I wanted to go beyond the 12-minute 4/4 acid track.

With Computer Space, you relied a lot on this stretching technique making samples from the TB-303 into pads and chords. Why did you want to re-appropriate this acid bass sequencer to make one of the most atmospheric albums in the trio?

RH: At the time most people including myself were making acid house as strong as it is right now. It was like fast distorted 909s and distorted 303s. And I was just like “man this machine is a beautiful machine and the 303 is at the heart of my sound”. And at many different stages later on and before I would just sit in front of the machine and think “how can I change the sound and still use it? How can I sequence it differently? How can I affect it differently?” At that point the [Akai] S950 sampler I was super fast on, and I thought “Can I use this to re-appropriate that [303] sound and in a way take it to the future? Can I make a 303 sound more futuristic than it sounds?”

The first time I heard the 303 it was so distinct. There’s just no other sound like it on the planet. So how do you then continue to follow up with 303 bass music having people, yourself included, feel like that again? When you looped it and stretched it, OK, there were strings and squelches but there was something robotic about it, something alien – nearly even cold – because I think the 303 naturally was quite warm. But partly with the looping and partly the S950 filters it was a really interesting experiment for me. “Can I make a 303 album without it sounding like a 303 album?”

The Computer Space sessions were very much a precursor to Plastikman. Was there anything in the making of that album that pushed you in this acidic direction?

RH: After Dimension Intrusion was done I was like “OK, fuck this, next album has to be a real album from beginning to end, it has to be recorded as quickly as possible, it has to have the same temperament and texture, and it just has to be a fully cohesive experience.” And honestly, I didn’t think Dimension Intrusion was that. The first thing I did with that mindset of locking myself away, reducing the amount of equipment and trying to create that atmosphere was Computer Space. The second thing I did after that was Sheet One. Most of Computer Space was done in a day or two days, and then there was another track that came later. And Sheet One was basically done in 48 hours, and one or two tracks came later. It was the texture and the feeling, the ambience, the atmosphere, the effects, how everything was patched together, how everything was bubbling – both times that became its own little world in my studio, became a specific album.

Maya-Roisin Slater is a music and culture journalist based out of Berlin and London. She recently stopped talking about riffs and started talking about frequencies. Find her on Twitter.

Richie Hawtin’s F.U.S.E. Dimensions 25th anniversary box set is available now from The Vinyl Factory.

Read next: Mark Fell on his love of FM synthesis and algorithmic composition

![Ryoji Ikeda installation data-cosm [n°1] extended at 180 Studios until 1 February, 2026](https://factmag-images.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/data-cosm-ALubbock_180-14Oct-3554-250x155.webp)

![180 Studios presents new Ryoji Ikeda installation, data-cosm [n°1]](https://factmag-images.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ryoji-ikeda-data-cosm-1-250x155.webp)