Words: K-Punk

For about five years, between 1992 and 1997, jungle sounded like the future rushing in. During that period, jungle was involved in a process of ceaseless reinvention, dismantling and reassembling itself – and assumptions about sound – before our amazed ears. It began as a mutation of rave, configured from elements of techno, dancehall, dub, rave, house, hip-hop and electro, but the volatile composite made for a sound that was completely unprecedented: futuristic and experimental, yet designed for the dancefloor.

Most rave had run on a 4/4 metric, but jungle was driven by the breakbeat. What fired this development was the enthusiasm of some ravers for hip-hop. Rave tracks ran at high bpms, and speeding up hip-hop breakbeats to nearly double tempo would have produced an unintentionally comic effect, but the technique of timestretching, which allowed producers to increase the tempo of a sample while keeping the pitch the same, enabled their use. The timestretched breakbeats, which subjected the funk of human drummers to machine-driven processing, gave jungle an uncanny cyborg-like feel. It wasn’t music entirely produced on machines, like techno.

Moreover, the breakbeats weren’t simply sampled and looped. Instead, they were fine tuned and micro-engineered, with individual drum hits manipulated on the sampler. The most important break in jungle was the so-called ‘Amen’ loop – a six second break taken from a funk track by forgotten group The Winstons. It had arrived at jungle via hip-hop. But unlike the hip-hop break, the jungle breakbeat did not function to keep time. Rather, it multiplied it, twisting and splintering it into an explosion of rhythmically polyperverse foldings and weird angles. At one level, jungle’s odd sense of time arose from running half speed dub basslines alongside 180 bpm breakbeats. Yet it was also the intricate involutions of the breakbeats themselves that produced the sense of temporal delirium, their enfolding recalling the impossible geometries of MC Escher’s work and justifying Kodwo Eshun’s description of jungle as “rhythmic psychedelia”.

Like rave, jungle fed off clubs, pirate radio and white label pressings. Unlike rave, though, jungle was an urban culture. Its constituency, defined by class rather than race, reflected the mixed ethnic make up of the inner city, and it was remarkable for being a sound made in equal parts by black and white producers. It was entirely appropriate, therefore, that one of jungle’s most famous figures, Goldie, would be mixed race. Jungle’s heartland was London and the Midlands (Coventry, of all places, was a particularly significant node), and in many ways the music developed out of the disintegration of the rave dream.

By contrast with rave’s Ecstasy-fuelled rural arcadia, jungle’s feral geography seemed as if it was derived from dystopian science fiction. Films were a massive presence, both as the source of samples and as something that coloured the mood and theme of tracks. The Alien films, with their paranoid spaces and techno-fetishism, the crashed ecosphere and artificial humans of Blade Runner, the cyborg stalker and timebending of the Terminator films, and Predator 2, with its dreadlocked monster and voodoo posse, were frequently referenced. But by fusing elements of science fiction and horror, jungle constructed its own Afro-futurist and cyber-gothic sonic fiction, set in the derelict arcades of a near future populated by millenarian rastas, cyberspace cowboys, voodoo loa and malign shape-shifting entities.

The jungle was a fictional space as much as a genre, a brutal ‘90s update of William Gibson’s cyberspace. Jungle’s innovations were collectively driven, not attributable to individual auteurs, but to ‘scenius’, the interaction between DJs, producers and the ‘massive’ on the dancefloor. Breakbeats and bass sounds would evolve from track to track, as if they were audio lifeforms subjected to an intense process of unnatural selection…

01. METALHEADS

‘TERMINATOR’

(SYTHETIC, 1992)

An early jungle classic, courtesy of one of the aliases of former graffiti artist turned sonic conceptualist Goldie and longtime collaborator Rob Playford. Rave flashbacks stab, breakbeats flare and fold in on themselves, while samples from Terminator’s Sarah Connor – “you’re talking about things I haven’t done yet” – sound as if they are commenting on the process of timestretching itself.

Loading Video…

02. BABYLON TIMEWARPF

‘DURBAN POISION’

(SUBLIME RECORS, 1992)

Named after a type of ganja, this track by the gloriously named Babylon Timewarp seems to follow a drug trade route into a UK housing estate. Beginning with slow skank guitar and heavy dub bass, it’s abducted into double time by breakbeats, rasta vocal samples and, incongruously but brilliantly, strings that sound as if they have a Middle Eastern provenance.

Loading Video…

03. TANGO AND RATTY

‘TALES FROM THE DARKSIDE’

(NO LABEL, 1992)

Translating rave frenzy into jungle dread, ‘Tales From The Darkside’ runs at a cartoon-hectic pace, with its stabbing riff sounding like pitched-up electro, Mantronix’s ‘Bassline’ running at +8. The brief, speeded-up-to-chirrup rap sample you hear, though, is from Eric B and Rakim.

Loading Video…

04. BAY-B-KANE

‘HELLO DARKNESS’

(RUFF GUIDANCE, 1992)

This one is all about the vocal sample: an inspired hijacking of the first two words from Simon and Garfunkel’s ‘Sound of Silence’, pitched up and looped. It’s an example of jungle’s ability to provoke the uncanny thrill of “déjà vudu” by altering and recontextualising a familiar sound. Witness the glee with which the darkness is being welcomed in – an indication of the way jungle found jouissance in dread.

Loading Video…

05. DOC SCOTT

‘HERE COME THE DRUMS’

(REINFORCED, 1993)

Early track from one of Jungle’s most consistent producers, fascinating because you can hear the music starting to establish itself as a style in its own right. The rules are only just being written, and you can still hear the building blocks, not yet smoothed out. Based around a lift from Public Enemy’s Chuck D, it’s gloriously ruff and ready.

Loading Video…

06. OMNI TRIO

‘RENEGADE SNARES’

(MOVING SHADOW, 1993)

Omni Trio were in fact one man, rhythm technician Rob Haigh, who painstakingly constructed his breakbeats out of individual drum hits. ‘Renegade Snares’ demonstrates Haigh’s rhythmic science at its exquisite peak, sweeping up a rave diva – “take me up” -into its thrillingly vertiginous swirl of breakbeats and poised, crystalline keyboards.

Loading Video…

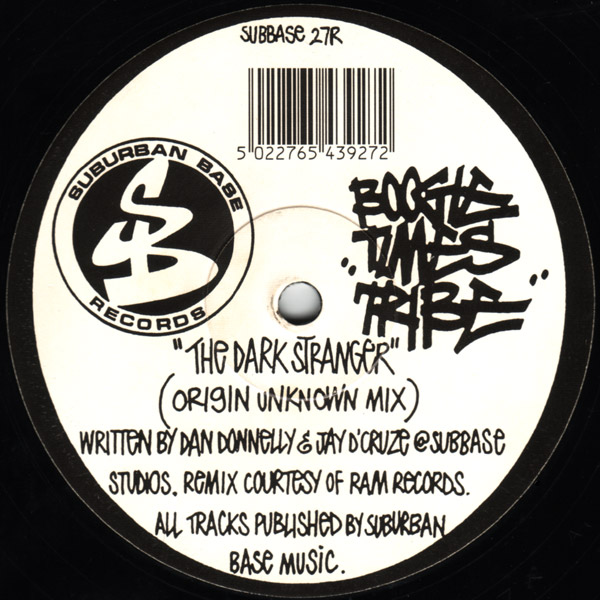

07. BOOGIE TIMES TRIBE

‘DARK STRANGER’, ORIGIN UNKNOWN REMIX

(SUBURBAN BASE, 1993)

One of many Jungle tracks which was based around a horror film. This ‘horrorcore’ classic features samples from a documentary about the making of Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula. Queasy synths bubble and flit, breakbeats crunch and punch, dogs bark, and in the background you hear gibbering laughter.

Loading Video…

08. SUBNATION

‘SCOTTIE’

(FUTURE VINYL, 1993)

“We’re all gonna die…” Another horrorsploitation track, this time distributing samples from The Evil Dead over chopped-up Amen snares. The early darkcore tracks possessed a deranged sense of humour, but, because there was no question of raised-eyebrow deflationary irony, there was no diminution in intensity. On the contrary, the ludicrous elements prevented early jungle from being weighed down by moody machismo, a vice to which the genre would eventually succumb.

Loading Video…

09. HYPER ON EXPERIENCE

‘LORD OF THE NULL LINES’

(MOVING SHADOW, 1993)

A crew with a superbly apposite name and an eye for a great track title too. This one is crudely bolted together out of rave-era piano and hypercharged FX, plus vocal samples from Predator 2 (“fuckin’ voodoo magic man”), and a diva on downtime (“there’s a void where there should be ecstasy” – a line that could serve as a slogan for the whole genre).

10. ORIGIN UNKNOWN

‘VALLEY OF THE SHADOWS’

(RAM, 1993)

“I felt that I was in this long dark tunnel.” An absolute classic, completely sui generis, also known as ‘31 seconds’, by Andy C and Ant Miles’s Origin Unknown. Psychedelic rather than dark, the arpeggiated electronics glisten. The samples this time are taken from a BBC documentary about near death experiences, an analogy, perhaps, for the way that jungle and narcotics took dancers out of their bodies.

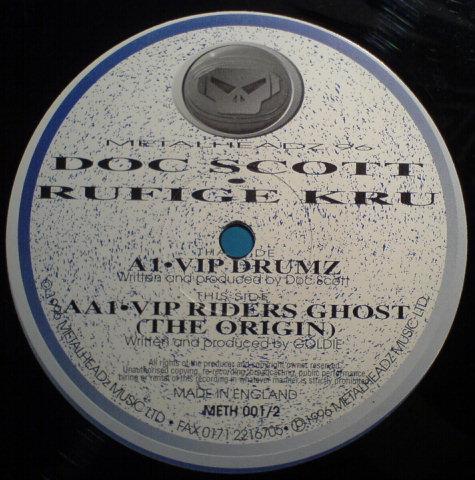

11. RUFIGE KRU

‘GHOSTS OF MY LIFE’

(REINFORCED, 1993)

Rufige Kru was another alias for Goldie and Rob Playford. An awful lot happened in the year after ‘Terminator’ was released. Virtually all traces of rave euphoria drained away, replaced by oozing electronic darkness. Here jungle reaches its deep winter, connecting to early-‘80s synthpop via a sample from Japan’s ‘Ghosts’ that slows David Sylvian’s vocal into a repeated mantra.

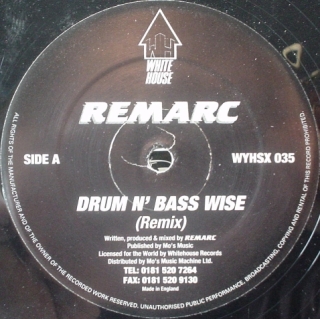

12. REMARC

‘DRUM & BASS WIZE’

(WHITE HOUSE RECORDS, 1994)

Remarc aka Marc Forrester was known as “the king of the Amen”, and ‘Drum & Bass Wize’, like his other classics ‘RIP’ and ‘Sound Murderer’, sees him expertly mash up the Amen break until it sounds like some possessed creature struggling to get off the leash. The ultra-vivid break seems as if it will punch its way through the speakers. Spiced, as was customary on Remarc tracks, by sampled amp-the-crowd chat from a Dancehall MC.

13. DJ HYPE

‘ROLL THE BEATS’

(SURBURAN BASE, 1994)

“T for tremendous.” The most potent jungle tracks used sampled vocals rather than MCs but ‘Roll The Beats’ served as a showcase for MC GQ, jungle’s most accomplished chatter on the mic. GQ rolled his r’s like Hype rolled his beats. And Hype further extended GQ’s already dilated r’s by the use of timestretching. The result is as if a percussive tic virus is passing between the breaks and the human voice, inducing a digital stutter.

14. MARVELLOUS CAIN

‘HITMAN’ (IQ RECORDS, 1994)

Based around bellicose breaks and an ultra-belligerent Cutty Ranks sample – “limb by limb wiafa cut them down” – ‘Hitman’ swaggers pugilistically. In the end, though, the dismemberment that it delivers is more an abstract than a literal violence, a celebration of the way that jungle’s Escher-esque rhythms cut up the body.

15. DEAD DREAD

‘DREAD BASS’

(MOVING SHADOW, 1994)

As you’d expect, a track showcasing the ‘dread bass’ sound that started to dominate jungle tunes: viscous, thick, acidic and wah wah-ish. The track’s much copied stop-start editing collages together timestretched-slow dread vocals, jittering-skittering cartoonish breaks, gunshot sound FX and rave diva vocals – “the burning light, the burning light…”

16. THE DREAMTEAM

‘YEAH MAN’

(JOKER RECORDS, 1995)

Simplicity itself, this track positively rolls forward, an exercise in pure propulsion. The hook is the title phrase, processed through electronic FX and timestretched down – a perfect example of the way in which timestretching often makes voices sound metallic, an effect exploited to the max in many jungle tracks.

17. DUBTRONIC

‘SCREWFACE 2’

(WHITE, 1995)

An example of jungle’s transfiguration of trash into treasure, this begins with a sample from Steven Seagal movie Marked For Death that is left to run virtually unadulterated for in excess of 40 seconds. ‘Screwface 2’ then cuts up and delays the sampled vocals into slow motion slices of timestretched dread: “Screwface’ll give me a t’ousand deaths worse than you… find him your fuckin’ self….”

18. SPLASH

‘BABYLON’

(DEE JAY RECORDINGS, 1995)

Dense with humid atmospherics, febrile with apocalyptic dread, centring on a sample from 1978 Jamaican film Rockers: “I and I know that all of the yout’ shall witness the day that Babylon shall fall”, with the “f-a-l-l” deliciously distended by timestretching. Incredibly, it includes a sample from none other than The Slits’ ‘Love Und Romance’: “Babylon lovers”.

19. DJ ZINC

‘SUPER SHARP SHOOTER’

(PAROUSIA, 1996)

‘Super Sharp Shooter’ anticipates the ballistic balletics of The Matrix, slowing, reversing and speeding up the sound of a bullet leaving a gun, and paralleling it with sampled and cut-up quick-fire rap from the Wu Tang Clan. Initially, it sounds like a junglistic take on slow-burn sleazy ‘70s street funk, before igniting into a frenzy of jump cutting, freeze-framing and rewinding.

20. TRACE/ED RUSH/NICO

‘DAMN SON’

(NO U TURN, 1997)

From the best Jungle LP, Torque, which showcased the taut style of the No U Turn crew. No U Turn had reduced jungle to a series of black and white abstract lines, hard yet sinuous. ‘Damn Son’ is a masterclass in the No U Turn art of building tension. There are some three-and-a-half minutes of loping, bone-dry breakbeats and high pitched-electronics before No U Turn’s trademark killer bass and the vocal sample – a fragment of between-track Wu Tang banter – kick in. No U Turn honed and perfected the techstep sound, but when others tried to follow where they had led, the results were too often leaden and ponderous. After this, Jungle’s joints would seize up, and speed garage would snatch the initiative.