In 2004, John Wood stood outside Hollywood’s Amoeba Records, selling bumper stickers emblazoned with the slogan: “Drum machines have no soul”.

“It’s a common-sense call for better music,” Wood said to his potential customers, canvassing support for his one-man crusade against the drum machine, the Society for the Rehumanization of American Music. When a journalist from the LA Weekly interviewed Wood at his apartment, he argued that modern pop music was to pre-70s pop music as pro wrestling was to professional boxing. “LL Cool J is not Marvin Haggler,” Wood said. “LL Cool J is Hulk Hogan.”

Wood’s campaign wasn’t just misguided, it was pointless. By 2004 the drum machine as an object was more or less done for. Its 80s heyday was over, largely replaced by software versions of what were crucial studio tools that had shaped not just pop music, but helped to invent hip-hop, house and techno. Wood probably wasn’t aware that software and recording techniques had become so advanced that even the intricacies of a jazz session drummer could be recreated inside a computer if you knew what you were doing.

It’s not difficult to see why Wood, a classically trained pianist, would dislike the drum machine. It was developed out of a practical need for a device that could provide rhythmic accompaniment when there was no drummer on hand. Drum machines went from simple playback devices to instruments that could be programmed; being cheaper than a real person, they made their way into the fabric of popular music before the technology advanced enough to make their sound indistinguishable from a real drum kit played by a human. The synthetic, rigid patterns they made lacked a human touch.

The earliest example of what could be considered a drum machine was the Rhythmicon, a device developed by Russian inventor Leon Theremin at the request of American composer Henry Cowell. Cowell wanted to use modern technology to do something that a human couldn’t do, in this case transpose multiples of a wavelength into beats, resulting in a device that created alien polyrhythmic pulses. Wood would probably have been horrified by it.

What the Rhythmicon did have in common with later drum machines was character unique to itself. Though the drum machine was created for practical reasons, a series of technological developments and happy accidents helped it to become a device that people used as passionately as a piano and as innovatively as the electric guitar. Whether Wood liked it or not, by 2004 it had created an entirely new musical language.

What follows is the story of 14 of the most important drum machines to shape that dialect, from the engineers that made them to the artists that used them.

Chamberlin Rhythmate

(1949)

Harry Chamberlin wasn’t the kind of person you’d imagine as the inventor of the modern drum machine. Born in Iowa, he helped to engineer the electrical system of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress during World War II, and for much of his early life he was an engineer who travelled the Midwest installing heating and refrigeration equipment.

Though Chamberlin was first and foremost an engineer, he was also a music fan who played in an eight-piece dance band in his youth. In 1949, at the age of 47, Chamberlin treated himself to the electric organ he’d always wanted, and bought himself a tape recorder so he could send recordings of himself playing the organ to his parents, who had moved to California. As he sat down to record himself, he had a eureka moment.

“I set [the tape recorder] on the bench next to me,” Chamberlin said in a 1976 interview. “And I was putting one finger down like this, and I said, ‘For heaven’s sake. If I can put my finger down and get a Hammond organ note, why can’t I get a guitar note or trombone note and get that under the keys somehow and be able to play any instrument? As long as I know how to play the keyboard, I could play any instrument.”

The result was the first multi-instrument keyboard, which he showed at the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM) in 1956. Underneath each key was a tape-playing mechanism loaded with pre-recorded instrument sounds; when the key was pressed down, a short tape loop would be played through a speaker. Chamberlin’s idea was later stolen by one of his own salesmen and reborn as the more famous Mellotron, but Chamberlin had not only created the world’s first electro-mechanical, polyphonic tape replay keyboard, he’d inadvertently created a very early form of sampler.

While Chamberlin’s keyboard was the the more famous of his creations, it wasn’t the first. His earliest tape-sampling device was a drum machine: the Chamberlin Rhythmate. It didn’t have any keys or buttons, just a sliding head that allowed the user to select between 14 tape loops of acoustic jazz drum kits playing different beats, some augmented with additional bongos, claves or castanets. It’s thought that only 10 of the original model were made, though in the 1960s, following the success of the Chamberlin keyboard, the Rhythmate was revived, selling a similarly modest 100 units.

The Rhythmate never achieved massive sales, but it set the standard for the next two decades of drum machines. The Rhythmate and Chamberlin keyboards were largely intended as devices for family sing-alongs, tapping into the market for the popular dances of the time, including the foxtrot, tango and waltz. The Rhythmate was a playback device, and though future models would add the ability to trigger rhythms, it would be a long time before the drum machine could be considered an instrument.

Wurlitzer Sideman

(1959)

One night in the early 1960s, Motown producer Hal Davis was told that the usual drummer at the lounge where he played couldn’t make it. Instead of cancelling the gig, he drove seven miles back to his house to pick up the Wurlitzer Sideman he had bought that day.

“After plugging it in, I was trying out some of the rhythms before getting ready to resume playing our next set,” he said in an interview. “The others of the group were busy watching while I tried to set it up. Suddenly, I looked up and saw three couples on the dance floor dancing to the rhythm of the Sideman all by itself.”

Listening to the Sideman now, it seems incredible that an audience in the 1960s would have danced so freely to a device whose sound must have been so alien. Unlike the Chamberlin Rhythmate’s tape loops, the Sideman’s rhythms were created by vacuum tubes and a valve amplifier. Its deep, rounded bass drums, brushed noise of its cymbals and shrill toms anticipated the sound of Roland’s TR series, yet the preset rhythms were much the same as the Rhythmate – popular dance standards like the samba, bolero and tango.

The Sideman was first introduced in 1959, 10 years after the Rhythmate. There’s no evidence to suggest that the Sideman was directly inspired by the Chamberlin’s invention, but the aesthetic and functional similarities between both suggest someone in Wurlitzer’s R&D division must have come across one. Like the Rhythmate, Wurlitzer’s Sideman was a tall, heavy cuboid device aiming directly at those who wanted some accompaniment for their organ, at home or in a performance setting.

While Chamberlin’s tape loop technology was able to recreate real drum sounds, it was prone to degradation and malfunction. The Sideman was different. Much like a simple music box, the Sideman’s patterns were generated mechanically by a rotating disc, something that made it much more reliable than the Rhythmate. The tempo could be controlled by a slider that changed the rhythm to anything from 34 to 150 beats per minute, and if you wanted, it was possible to trigger each of the 10 drum sounds individually from a bank of buttons on the side of the control panel. While the Rhythmate was little more than a glorified tape player, the Sideman generated its own sound.

The Sideman took its name from the term for the musicians that would be hired to accompany soloists. While this was likely used by Wurlitzer in an ironic fashion, the American Association of Musicians didn’t see it that way. Unlike the Rhythmate, which sold a tiny number, the Sideman was incredibly popular, and it attracted the same criticism from the unions that Chamberlin’s keyboards did a few years before, when the union ruled that one could only be used in cocktail lounges as long as the keyboard player was paid the wages of three musicians.

Despite the early drum machine’s success, Wurlitzer stopped manufacturing the Sideman in 1969. Eventually the company would cease production of organs and jukeboxes too. Today, the company lives on as a manufacturer of vending machines, automation the only thing that connects it to its former position as a powerhouse in the world of music technology. But Wurlitzer’s musical legacy didn’t end there. In 1962, a Japanese man bought a Sideman, spawning not just another drum machine, but one of the biggest music hardware companies in the world.

Keio Minipops MP-5/MP-7

(1967)

Like Harry Chamberlin, Tadashi Osanai was both a musician and an engineer. He played accordion at a nightclub in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, and like Hal Davis, he used a Wurlitzer Sideman to accompany his performances. Osanai, however, was frustrated by the Sideman’s limitations. The nightclub’s owner was Tsutomu Katoh, a former submariner who by 1960 also owned a discount store and a music shop. Osanai convinced Katoh to fund his idea for a better drum machine than the Sideman. Over 50 years later, their company still exists as Korg.

Before the Korg name existed, their business was called Keio, named after the railway line next to the central Tokyo factory that housed Osanai and his team of four employees. Their first product, made in 1963, was the Keio Gijyutu Kenkyujo DA20 DoncaMatic Disk Rotary Electric Auto Rhythm Machine, a device that used much the same disc system as the Sideman. In 1966 it was superseded by a solid-state version powered by transistors. It might have been less limited than the Sideman, but it was still a hefty piece of equipment.

The Doncamatic is still fondly remembered (especially by Gorillaz), but it was the Minipops, released later that year, that was to set the standard for the drum machines of the future. As well as being powered by more reliable transistors, the Minipops was small. No longer did you have to carry a sideboard-sized device with you if you wanted a drum machine – now there was a product that could sit on a tabletop.

The Minipops originally came in two models: the MP-5 and the MP-7. The MP-5 was the smaller, more basic of the two, offering 10 preset rhythms, with controls for tone, tempo and volume. The MP-7 offered 20 rhythms with tempo and volume control, and had dedicated faders for adding ouijada, guiro and tambourine. Most notably, the controls allowed the user to press more than one preset to combine rhythms.

The Minipops would go on to have a long lifespan, spawning another six models, including two produced after Keio had changed its name to Korg and begun making monophonic synthesizers. Though the drum sounds were still primitive, they had their fans, most notably Jean-Michel Jarre who immortalised the MP-7 on his album Oxygene. For all the drum machine’s portability however, the MP-5 and MP-7 were still devices bound to dance rhythms like the rhumba, tango and bossa nova. It wasn’t until 1975 that the drum machine would start to become a tool for composition.

PAiA Electronics Programmable Drum Set

(1975)

John Simonton Jr was a hobbyist, who, along with his father, enjoyed tinkering with electronics. In 1959, a full eight years before they started selling mail-order synth kits and Simonton Jr began working at the first computerized jet engine facility in Oklahoma, the pair founded their own company as a means of expensing their hobby for tax purposes. Their first commercial product was a circuit board for a home security system called the Cyclops Intruder Detector, and was a commercial failure. If it hadn’t been for the more successful Omni-Alarm for alerting automobile malfunctions, PAiA Electronics might have folded before it even got going.

PAiA’s heyday was in the 1970s, when interest in modular synthesizers was at its highest, but prices at their most expensive. Instead of selling to high-end users, Simonton tapped into the DIY market, selling kits to hobbyists who could build them into both modular and all-in-one analog synths. While Moog and ARP’s synthesizers cost anything between $5,000 to $10,000, a basic keyboard synthesizer kit from PAiA cost just $230. As well as synths, PAiA sold drum machine kits. Its first was the Drummer Boy, a small unit much like the Korg Minipops, complete with similar preset selections and similar limitations. The real innovation came with the Programmable Drum Set.

It wasn’t the first programmable drum machine. That was the Eko ComputeRhythm in 1972, but only a handful were made – PAiA’s effort made the function affordable. There were no buttons to speak of on the device, just touch-sensitive controls that triggered heavy bass, light bass, snare drum, rom-tom, conga, wood block and clave. The sounds were created by what were called “ringing oscillators”, which used a filter close to oscillating that would ring like a real drum when hit by a pulse. The sound it made was as basic as the Wurlitzer Sideman, but inside was a 256-byte memory that saved user-defined patterns in any time signature. It didn’t just save one basic pattern: it allowed score editing as well as the creation of bridges and intros.

PAiA’s Programmable Drum Set only had about a year before other companies started making their own more widely adopted programmable devices, but it did make its way onto Peter Gabriel’s 1980 track ‘Games Without Frontiers’. The market for DIY synths dwindled in the 80s as hobbyists shifted over to the growing interest in building personal computers, but the company still makes synth module kits for dedicated enthusiasts.

PAiA’s role in the development of the drum machine may have been brief, but it was important. For the first time, musicians were no longer limited by the patterns imposed on them by the manufacturers. Instead, the drum machine was a futuristic tool capable of creating rhythms unshackled from the canon of western music. However, it was to be another Japanese inventor that would bring the programmable drum machine to its full potential.

Roland CR-78 Compurhythm

(1978)

After losing his parents to tuberculosis when he was two in pre-war Japan, Ikutaro Kakehashi spent much of his childhood studying electrical engineering and working in the Hitachi shipyards of Osaka. He failed to get into university in 1946 on health grounds, and moved to the southern island of Kyushu, where he took advantage of an opening in the market for timepiece repair. Soon he was repairing radios too, and returned to Osaka with enough money to fund his entry into university.

It was at this point, aged just 20, that Kakehashi himself was struck down with tuberculosis, spending three years in hospital. He was only saved when he was picked to trial an experimental drug called Streptomycin. If Kakehashi hadn’t recovered, the modern musical landscape would be very different. In 1972, he founded Roland, the company that arguably did more to shape electronic music than any other in history.

LIke Keio’s Tadashi Osanai, Kakehashi was fascinated by the Wurlitzer Sideman. Prior to the foundation of Roland, and after he’d gone back to a life of electronics repair, he owned Ace Electronics Industries, a company that took a drum machine called the R1 Rhythm Ace to NAMM in the USA. It was smaller than Keio’s Doncamatic, and was said to be the world’s first transistored drum machine. It was also a complete flop. Without pre-programmed patterns, the R1 was a performance device the world just wasn’t ready for yet.

Kakehashi had much success with the drum machines that followed, but it would be 14 years before he created a device that offered a real advance in the technology. The aesthetic of the Roland CR-78 Compurhythm was a lot like his original R1, but as well as having preset rhythms it featured the PAiA’s ability to write and store your own rhythms in one of four memory banks, even after the device was turned off.

Unlike the PAiA, the CR-78 required the laborious use of the WS-1 Write Switch, but the combination of programmability and familiar preset rhythms made it popular with both home users and artists like Phil Collins and Blondie. “In reality, it was a non-dancing Japanese programmer’s idea of strange Western generic rhythm patterns, so inevitably eccentric and electronic sounding – which endeared it to me immediately,” said Ultravox’s John Foxx. “I liked the CR78’s primitivism, and found I kept on going back to it. I came to understand that its rigidity forces you to work in certain ways and I like that.”

The CR-78 was the end of an era. Its wooden exterior was one of the last to be directly inspired by the Sideman, which by now was over 20 years old. Though future drum machines would also come with presets, the CR-78 was one of the last to feature them so prominently; it was 1978 by this point, and the market for bossa nova, samba and foxtrot rhythms was drying up. People wanted something they could play, not a cocktail lounge rhythm machine.

Linn LM-1

(1980)

The CR-78 might have offered programmability, but an industrial designer called Roger Linn was still dissatisfied with what the devices of the time had to offer. Speaking to Mark Vail in 2000, he said that he “wanted a drum machine that did more than play preset samba patterns and didn’t sound like crickets.” In 1978, he set out to make his own programmable device, one that was more suited to his needs as a guitarist.

Having taken classes in the BASIC computing language, Linn took an analog voice generator from an existing Roland drum machine, and wrote some software capable of creating patterns. Despite having a method of pattern creation he felt happy with, there was still the sound engine to improve on. It was Toto guitarist Steve Pocaro who suggested Linn sample recordings of real drums digitally, giving him the breakthrough he needed.

Linn wasn’t the first person to use digital sampling technology. The method was pioneered by Peter Grogono, David Cockerell and Peter Zinovieff in 1967, when they released the EMS Musys, a system that required two computers to run. By 1978, the technology required to store digital data had become smaller and more affordable, and Linn was able to use a single chip to store 12 8-bit samples: kick, snare, hi-hat, cabasa, tambourine, tom, conga, cowbell, clave, and hand clap. The most notable omissions were ride and crash cymbal.

The result was the Linn LM-1 Drum Computer, the world’s first drum machine to use digital samples. Unlike the tape recorded samples of Chamberlin’s Rhythmate, Linn’s would never degrade. It had a staggering 100 memory patches for storing rhythms, and unlike Roland’s CR-78, patterns could be created using the LM-1 control panel, which took its cues from the personal computers of the era.

The LM-1 was however, very expensive. At $4,995, Linn didn’t break the mass market until the release of the LinnDrum in 1982, but the LM-1’s power made it appealing to professionals. Each voice could be individually tuned and mixed, making it one of the first devices that could be easily used in professional studios. Throughout the 80s the LM-1’s sound was inescapable: ABC, Devo, Giorgio Moroder, Michael Jackson and John Carpenter were just some of the artists who used it on records.

Perhaps the most important breakthroughs the LM-1 introduced were the shuffle function and note quantizing, which Linn told Attack in 2013 he discovered by accident. “When I ran my real-time recording code and played the drum buttons in time to the metronome, I noticed that what I had recorded played back on perfect 16th notes, effectively correcting my timing errors, so I decided to call this bug a feature, which I called ‘timing correct,’” he said. “In considering how to compress swing-time beats, it occurred to me that this could be done by delaying the playback of alternate 16th notes, and by varying the amount of delay I could vary the degree of swing. And so the swing feature was born, which in 1979 I called ‘shuffle’.”

Through a simple mistake, Linn had proved that drum machines could have some of the soul of a human percussionist, a feature notably missing from Roland’s offerings for several years. Prince took the use of the LM-1 into an art form: there’s even a forum page devoted to figuring out how he got the “knocking sound” on ‘When Doves Cry’. The sound of the LM-1 seems very dated next to today’s drum kit sample packs, but they probably wouldn’t exist without it. Linn’s creation and the records it spawned had proved that sampled drums could be just as expressive in the right hands.

Roland TR-808

(1980)

“The TR-808 is a piece of art,” said Robert Henke in an interview with The Wire in 2010. “It’s engineering art, it’s so beautifully made. If you have an idea of what is going on in the inside, and if you look at the circuit diagram, and you see how the unknown Roland engineer made the best out of super limited technology, it’s unbelievable.”

Despite the opinion of Henke being shared by music fans across the world 35 years after its release, the most iconic piece of music production gear ever was seen as a failure when it was launched in 1980. Like Roger Linn, Roland’s team wanted to make a programmable drum machine for backing tracks, but where Linn used digital samples, Roland’s analog sounds were provided by transistors.

On a technical level, Linn’s effort totally surpassed the 808. While the LM-1 had an innovative shuffle function and realistic drum sounds, the 808 had a metronomic rigidity and tinny cowbells that sounded more like sci-fi sound effects. The synth tones and white noise that made up the 808’s primitive drum sounds were seen as inferior by reviewers and professional musicians, and the 808 struggled to find an audience, despite costing over $3,000 less than the LM-1.

Though the Yellow Magic Orchestra were the first to use the 808 on stage, it wasn’t until 1982 that the drum machine was to enter popular consciousness. Afrika Bambaataa & The Soulsonic Force took inspiration from the angular sounds of Kraftwerk and applied it to a hip-hop template, utilising the sheen of the 808 and creating ‘Planet Rock’. Around the same time a Detroit musician called Juan Atkins purchased an 808 and put it to use in his group Cybotron. In both cases, the 808’s uncanny, futuristic sound was celebrated for what it was, and artists began to come around to the unit’s perceived limitations.

After the unit was discontinued in 1984, the second-hand market began to fill with 808s, available for a fraction of their original price. Everyone from Egyptian Lover through Richie Hawtin to Throbbing Gristle’s Chris Carter purchased an 808, though its thread runs strongest through hip-hop culture as the backbone of 80s electro, Southern production, and Miami Bass. As Questlove has said, the 808 was “the rock guitar of hip-hop.”

Today, producers continue to be obsessed with the 808’s unmistakable sound. Its drums form the backbone of Chicago’s footwork scene, which in turn inspired producers like Addison Groove to use the sound in their own mutations. Even in today’s post-genre landscape, the 808 is the familiar trope that links many disparate styles.

Oberheim DMX

(1981)

By the time Tom Oberheim set about designing his own drum machine, he was already a prolific figure in the world of synthesis. He’d gone from building hi-fi components for his friends at school to designing the world’s first programmable monosynth, and in 1980 he set about designing a device to capitalise on the popularity of Roger Linn’s LM-1.

Like the LM-1, the Oberheim DMX was a machine that used digital sampling technology to achieve realistic drum sounds. Similarly, the DMX used an 8-bit digital format to store its drum samples, but Oberheim’s device used an algorithm to increase the resolution to 12 bits. Combined with the same Curtis 3320 voltage controlled filters found in the Prophet-5, the DMX was capable of realistic yet unmistakably warm and robust sounds, at a considerably lower price than the LM-1.

While the LM-1 found its way into many professional studios, the DMX was the machine that managed to crack the emerging hip-hop scene. While Roland’s TR-808 was already starting to find popularity in that field, the DMX was as important in shaping the genre’s sound. Released in 1983, Run-D.M.C.’s ‘It’s Like That’ was one of the first notable uses of the DMX in hip-hop, and the DMX’s drums helped to shape the idea of a hip-hop beat.

It wasn’t just hip-hop where the DMX was adopted. The same year, New Order used the DMX on ‘Blue Monday’, while Madonna’s ‘Holiday’ and ‘Into The Groove’ placed the DMX sound further into the collective consciousness.

While the DMX had humanising features like rolls, swing and flams, it was later expanded with a device called the Prommer. The DMX stored its drums on a programmable memory chip called an EPROM, which could be removed from the drum machine, and the Prommer allowed the user to burn their own drum samples onto a extra chip. In effect, the Prommer was an early form of sampler, albeit one that was useless unless you had a DMX. The real revolution in sampling was just around the corner.

E-Mu Systems Drumulator

(1983)

Though Roger Linn had had created the first drum machine to use digital samples, and followed it up with the more affordable Linndrum in 1982, cost was still a major barrier to entry. At $2,995 it was still out of the range of all but the most dedicated musicians and the Oberheim DMX, costing $2,895, wasn’t much better. However, a company called E-Mu had the knowledge and the experience to do things cheaper. Much cheaper.

E-Mu was founded by Scott Wedge and Dave Rossum in 1970. Though it started off making its own modular systems, across that decade it made most of its money licensing technologies to other synth companies, most notably the digitally-scanned keyboard architecture and integrated circuits inside the Sequential Circuits Prophet-5. It was these SSM chips, co-designed with an engineer called Ron Dow, that the company put to work in its first drum machine.

Rossum’s extensive experience with chips meant that he was able to develop a drum machine that shared components to cut costs, using a single 64kb sample memory instead of dedicated chips for each drum. Rossum also trimmed the fat from the Linndrum’s interface, electing to use just a single slider for entering data, and include only four trigger buttons to map drums to. The trade-off was much shorter sample times than the LM-1 or Linndrum, and a much less user-friendly interface, but it meant it could retail for just $995.

The E-mu Drumulator was a massive success, going on to sell 10,000 units in a two-year period. While it helped to bring the drum machine to a wider audience, it was perhaps its successors that were more important. The E-Mu SP-1200 added the ability to record your own drum sounds, creating the blueprint for the modern sampler and paving the way for everything from the Akai MPC to the Boss Dr. Sample.

While Roland’s TR-808 and TR-909 are often cited for their importance in the development of dance music, the Drumulator’s legacy is just as important. As well as the house of Todd Terry, French touch pioneers Daft Punk and Alan Braxe used the SP series. Today it’s still used by producers like Willie Burns, who use its limitations to achieve a classic house sound.

Sequential Circuits Drumtraks

(1984)

By 1981, the synth business was booming. Bulky modulars had given way to more practical all-in-one models, monosynths had been joined by polysynths, and a year previously Yamaha had released the first FM digital synth, the GS-1. The problem was that everything but analog monosynths proved incompatible with the older control voltage standard. Companies begun creating their own proprietary connection methods, but this just made things more difficult for the consumer, who wasn’t able to connect competitors models.

It’s rare that companies ever work together to make things easier for the consumer, but that’s exactly what happened. Roland’s founder Ikutaro Kakehashi suggested the idea of standardisation with Tom Oberheim, who proposed it to Dave Smith, president of Sequential Circuits, the company responsible for the iconic Prophet-5. Smith, together with Chet Wood, and in consultation with the major Japanese and US manufacturers, developed a universal interface that would allow any synthesizer to communicate with another. The result was MIDI, a system that is still the standard today.

Though MIDI was demonstrated at NAMM in January 1983 with a Sequential Circuits Prophet 600 and a Roland Jupiter-6, it had applications beyond synthesizers. As soon as the MIDI standard was finalised, Smith set to work on the world’s first MIDI-equipped drum machine, the Sequential Circuits Drumtraks. The result was an 8-bit sample-based drum machine with real sounds similar to the Linndrum LM-1, though perhaps a little grittier and more straightforward to program.

With MIDI however, the drum machine could finally be the reliable hub of a larger setup. Unlike control voltage, which was prone to drifting out of time, MIDI was accurate, though this wasn’t anything that CV hadn’t been capable of before. Perhaps the most important thing the Drumtraks’ MIDI connection allowed was for the transmission of MIDI messages affecting volume dynamics and accents. You would need to connect a velocity-sensitive keyboard like SC’s Six-Trak to do it, but for the first time there was a drum machine capable of expression.

The Drumtraks was quickly superseded by the more advanced TOM in 1985, and never quite caught on in the way that Roland’s machines did, but it showed just what could be achieved with a MIDI-equipped drum machine. Sequential Circuits went out of business in 1987, but Dave Smith went on to work for Yamaha, and developed the world’s first software synth to run on a PC. It would be 25 years until he returned to the drum machine, and with it, helped revive the interest in what had become an obsolete technology.

Roland TR-909

(1984)

By 1984, Chicago DJ Frankie Knuckles had already made his name at the city’s Warehouse club, and had opened his own club, the Power Plant. A young DJ called Derrick May would often make the journey from Detroit to Chicago to see Knuckles play, and one day he called him up to ask if he wanted to buy one of the two drum machines he’d gotten his hands on. May offered to help him figure out how to program the device, and Knuckles was hooked. The first track he used it on was a version of ‘Your Love’ he did with Jamie Principle, and Knuckles began to play the drum machine underneath records in the club. Knuckles had set the template for almost all house music that would follow.

The drum machine May had sold Knuckles was Roland’s TR-909. The successor to the 808, it was a part analogue, part sample-based drum machine that took advantage of the new MIDI technology and featured a 16-step sequencer based on its predecessor. Despite the more realistic drum sounds this technology achieved, the 909 had an even shorter shelf life than the 808. Roland finally conceded that it needed to release a fully sample-based drum machine to compete with its rival, and the 909 was replaced by the TR-707 just a year after its initial release.

Like the 808, the 909’s life didn’t begin until well after its demise. Producers in Chicago, inspired by Knuckles’ use of the instrument at the Power Plant, began to buy their own 909s. The 909’s kick drum felt like being punched in the gut when played through a large system compared to the 808’s comparatively more gentle sound, and lent itself to keeping the energy going at Chicago’s house clubs. Just as the high and low end frequencies of the 808 created a new sonic context in which to work, the 909 brought a new kind of power and momentum other drum machines had been lacking.

Meanwhile in Detroit, the 909 was starting to get picked up by the city’s emergent techno scene. A young DJ called Jeff Mills was inspired to use it in his sets by Chicago’s Farley Jack Master Funk, Kenny “Jammin'” Jason and Bad Boy Bill, and the 909 quickly became not just a tool for Mills, but a way of life. “The TR-909 circuits and sound boards created the right balance of resonance that it sounded pretty much like the drums we heard on existing records,” he said in an interview in 2011. “It was more brutal.”

Mills was by no means the only producer using the 909, but he took its potential further than anyone. In 1988, Mills founded Underground Resistance with Mike Banks, creating 909-fuelled techno more uncompromising than anything that had come before it, both musically and politically. When Mills went solo in 1991 he continued to take the form into harder, darker places, turning his 909 into a hypnotic tool. Recently, Mills even gutted his original 909 and turned it into a custom-designed instrument shaped like a UFO.

The 909 kick may not be used as much as it was, but modern techno owes a considerable debt to Mills’ approach, while contemporary house is still shackled to the kind of unmistakable thump Frankie Knuckles helped to popularise. The TR-909 may have been a stopgap before Roland finally released the drum machine it felt it needed to beat the likes of the Linndrum, but it unwittingly created the pulse of the modern nightclub.

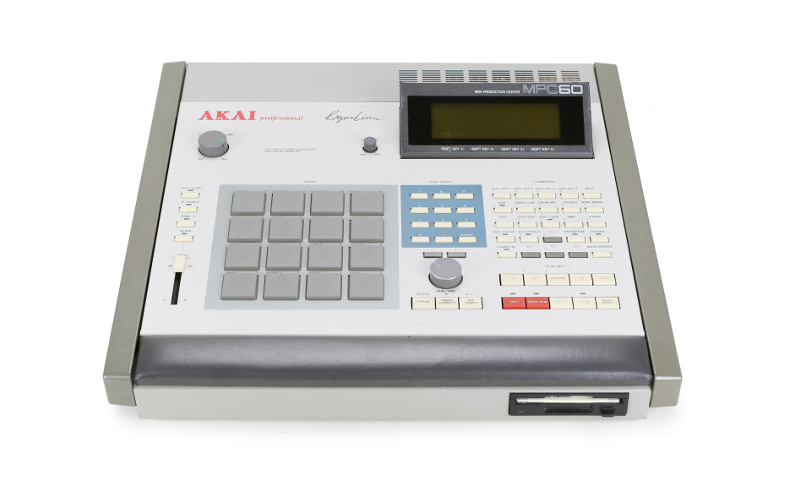

Akai MPC60

(1988)

The LM-1 had been a huge success for Roger Linn, but it wasn’t enough. In 1986, strong competition and bad publicity due to the temperamental software in his Linn 9000 model forced Linn Electronics out of business. Despite the failure of his company, his expertise was still very much in demand, and he was headhunted by Japanese company Akai, who put him to work on their recently launched division for electronic instruments, Akai Professional.

Compared to Roland, Korg and Yamaha, Akai was woefully inexperienced in the business of making music production gear. The company had released a few digital samplers to capitalise on the technology, but their efforts were being trounced by E-Mu’s SP series, which at the time of Linn Electronics’ demise was already being used by Rick Rubin to produce the Beastie Boys’ debut album. Their rack mounted efforts lacked the hands-on feel of the LM-1 drum machines that the SP series had taken inspiration from. Roger Linn was the ideal person to beat E-Mu at their own game.

The result was a drum machine sampler and MIDI sequencer called the MPC60. It took design features from Linn’s own Linn 9000, including velocity-sensitive drum pads and user sampling capabilities, and added higher audio quality, a floppy disc drive and the ability to play 16 voices simultaneously. The MPC60 wasn’t just a drum machine with the option to add your own samples, it was an entire workstation. The loop-based limitation of the SP-1200 had been superseded, and many of the hip-hop artists who had popularised sampling in the 80s swapped their SP-1200s for MPC60s.

The MPC60 and its offspring’s impact on modern music was massive, especially in hip-hop. DJ Shadow recorded all of his debut album Endtroducing using the MPC60, while Theo Parrish and Moodymann would eventually bring a more organic feel to house music using the MPC. The reason for its signature looseness was Linn’s famous quantise and swing, which corrected rhythmic error without sacrificing a human touch. Other manufacturers have their own quantise and swing functions, but a lot of artists maintain Linn’s has something unique about it others lack.

Linn was let go by Akai after the MPC60 was released due to disappointing sales, but the MPC proved to be a slow-burn affair. Slowly but surely its popularity increased until Linn was asked back by the company to develop an even more powerful model, the MPC3000. The partnership dissolved once again and Linn went on to form Roger Linn Design, a company that dealt in guitar effects units. It was something he’d focus on for years, until a former rival convinced him to design one more drum machine.

Native Instruments Maschine

(2009)

At the end of the 2000s, the computer had won. Expensive synthesizers were replaced by software versions, MPCs and sequencers were replaced by Ableton to arrange tracks, and most of the hardware being made were MIDI controllers designed to control parameters on a screen. In 1980, a Linndrum would have cost $4,995; in 2009 you could get a software version that made pretty much the same sound for free.

It wasn’t just having access to any retro sound that killed the drum machine, it was the vast possibilities of software. Programs like Battery allowed you to tweak every possible parameter of a snare drum in minute detail if you wanted, allowing producers to craft the kind of sleek, atomised rhythms that propelled the minimal techno boom. It made little commercial sense to release a real drum machine at this point; tastes changed so quickly that any presets would have been outdated within a year of release. Producers needed to be able to make their own drums, and a controller, software and sample library was what they needed.

There was a healthy number of drum pad MIDI controllers to choose from in the 2000s. Models from Akai, M-Audio and Korg ruled the marketplace, but something was missing. While MIDI would allow producers to map controls how they liked, these products were catch-all devices that resulted in some kind of disconnect between hardware and software. While these devices could be used to sketch out beats, producers would largely find themselves using a mouse and keyboard to change values, switch presets and add effects.

It wasn’t a hardware company that cracked the problem, but one known for its software. Native Instruments set out to develop a hybrid of hardware and software that looked and functioned like a classic drum machine. The result was the Maschine, a sleek, lightweight device series with controls designed for the accompanying software’s functionality. Hundreds of drum sounds were accessible from the device itself, hosted on the user’s computer, which did the sequencing.

Since Maschine was launched in 2009, it’s added full drum synths to its sample library, as well as the ability to host VSTs. It’s more of a workstation than a one-function tool now, a successor to Roger Linn’s MPC series that trumps Akai’s own recent attempts to revive the MPC for the software era. The inclusion of elements like a swing knob have made it something that users of classic drum machines can feel at home with.

The Maschine is arguably one of the most ubiquitous electronic instruments of the past decade, used by everyone from aspiring hip-hop producers to veteran producers like Carl Craig. It’s difficult to judge what its influence is or what its legacy will be – it’s the most powerful electronic rhythm creation tool in history, but with over a thousand kick drums alone to choose from, it doesn’t really have a sound to speak of. What it has done however, is to make the drum machine accessible to more people than Roland, Korg and Yamaha put together.

Dave Smith Instruments Tempest

(2011)

Native Instruments might have united software and hardware, but there were still producers who wanted the sound and experience only a hardware drum machine could offer. As software flourished in the late 90s and 00s, the second-hand market was flooded with vintage drum machines. Whether they were picked up from thrift stores or purchased on eBay, the prices were low enough and supplies plentiful enough for most people to get what they wanted reasonably easily.

Towards the end of the end of the 00s, this began to change. The increased fetishization of vintage gear for its aesthetic qualities, hands-on control and analog sound led to inflated prices and a lack of availability on the second-hand market, partially driven by a revival in the interest of old school house and techno sounds. While software offered the ability to have almost any classic drum machine at your fingertips, a lot of audiophiles maintained that there was nothing quite like the analog punch of a real 909 kick.

In 2006, Dave Smith’s new business, Dave Smith Instruments, was proving that there was still a market for brand new synthesizers powered by analog technology. His Evolver and Prophet ‘08 units filled the gap left by the analog synths of the 70s and 80s, and he decided to do the same with the drum machine. He contacted Roger Linn, at this point designing guitar effects, and suggested they combine expertise. The first incarnation of their drum machine was the BoomChik, a prototype that looked like an MPC with a rack synth bolted on, and early reactions weren’t great.

By the time it was released as the Tempest in 2012, their creation looked much different. More than just one of the best drum machines ever constructed, the Tempest could double up as a six-voice synth. Each voice was comprised of two analog oscillators and two digital oscillators, allowing for a depth of sound you couldn’t have achieved with any 80s analog drum machine. The inclusion of 16 expressive pads and two touch controllers where you might expect to find pitch and modulation wheels on a keyboard backed up the pair’s vision of the Tempest as “a rethinking of what a drum machine needs to be in the current era.”

Not everyone loves the Tempest. There’s a whole forum post asking who kept it after the initial rush of hype, with people citing everything from the complexities of the workflow to the lack of punch in the kicks. What it does have, is a character all of its own, helping to shape the sound of the current generation of raw techno producers. Blawan and Pariah’s Karenn project uses a Tempest to anchor their music in a gritty rhythmic backbone, while utilising its synth capabilities for basslines. Barker and Baumecker used it on a few tracks on their 2012 album Transsektoral, the classic Linn swing giving their take on techno a playful dimension.

The Tempest’s high price might have kept it out of the reach of many producers, but it filled a gap the Maschine couldn’t, and helped make drum machines desirable again. In 2014, Elektron released the RYTM, an analog drum machine that arguably wouldn’t have existed without the Tempest. Roland followed that with the AIRA TR-8, an affordable modern update of its 808 and 909 models. While most producers are still likely to reach for the Maschine if they’re making rhythms, the Tempest helped give a fresh lease of life to a much loved instrument that started life as a giant cassette player.

Scott Wilson is on Twitter.