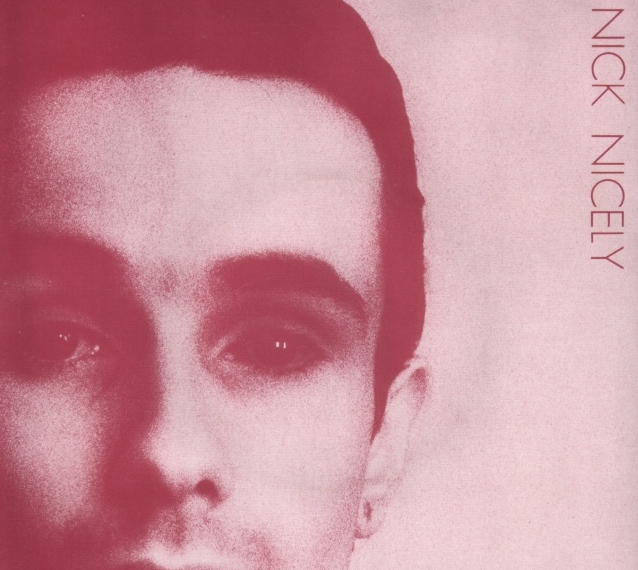

Nick Nicely has never sold many records, has never troubled the upper reaches of the charts, has never had much more than a cult following. He is not, by any stretch of the imagination, a popstar. But he should’ve been – he had the songs, he had the talent, he even had the record deal. So what on earth went wrong?

Born Nickolas Laurien in 1959, raised in Hitchin and Deptford, Laurien’s love affair with pop began early, when his brother introduced him to British radio; the boundlessly imaginative sounds he heard over the airwaves then, and the images and ideas they triggered in his own mind, would remain his bedrock of inspiration over the next forty-odd years.

“When ‘DCT Dreams’ was finished and on their desks they shut the fuck up about letting me go.”

As the 60s bled imperceptibly into the 70s, the increasingly sophisticated Laurien turned to albums for nourishment, and today cites Nice Enough To Eat – a 1969 Island compilation that brought together guitar freak-outs, blues, pastoral folk and psych from the likes of Dr Strangely Strange, King Crimson, Fairport Convention and Nick Drake – as a key formative discovery.

At the age of 17 he began to hang around a local folk club, taking the opportunity to sing whenever he could, getting a feel for harmony that serve him well in his impending career as a songwriter and performer. He left home and set himself up in London, playing guitar in various lacklustre college bands and, more importantly, beginning to apply his energies to penning his own material.

He honed his songcraft over the course of the mid-late 70s, a period which didn’t much resonate with him musically, save for “Kraftwerk, Neu!, Can and the Euro end of disco.” In ’78 his DIY recordings caught the attention of well-known London publisher Heath Levy, who looked after serious unit-shifters like The Eagles and Steve Miller. They were hoping to install Laurien as an in-house songwriter, penning hits for established and emerging acts, but he had different ambitions. Heath Levy were ready to let their impudent charge go, even after hearing his terrific ‘1923’ demo, but Laurien was determined to be taken seriously as a recording artist in his own right, and knew that with access to the right facilities he could create something of incontestable merit. “I blagged the engineer [Rudi Pascal] to let me take over their small studio there in Regent Street and record all night,” he recalls. “When ‘DCT Dreams’ was finished and on [Heath Levy’s] desks they shut the fuck up about letting me go…unfortunately.”

He honed his songcraft over the course of the mid-late 70s, a period which didn’t much resonate with him musically, save for “Kraftwerk, Neu!, Can and the Euro end of disco.” In ’78 his DIY recordings caught the attention of well-known London publisher Heath Levy, who looked after serious unit-shifters like The Eagles and Steve Miller. They were hoping to install Laurien as an in-house songwriter, penning hits for established and emerging acts, but he had different ambitions. Heath Levy were ready to let their impudent charge go, even after hearing his terrific ‘1923’ demo, but Laurien was determined to be taken seriously as a recording artist in his own right, and knew that with access to the right facilities he could create something of incontestable merit. “I blagged the engineer [Rudi Pascal] to let me take over their small studio there in Regent Street and record all night,” he recalls. “When ‘DCT Dreams’ was finished and on [Heath Levy’s] desks they shut the fuck up about letting me go…unfortunately.”

‘DCT Dreams’

‘DCT Dreams’ was Laurien’s official debut single as Nick Nicely. On first listen it’s hard record to place historically, combining as it does a 60s soft-psych classicism with the synthetic chutzpah of the coming 80s (Laurien is keen to acknowledge how much hearing early Human League and Tubeway Army galvanised him). It might sound glib to describe ‘DCT Dreams’ as synth-pop on acid, but that’s precisely what it is. At this point Laurien really was taking a lot of acid.

“The acid had ‘rehardwired’ my brain, including my musical tastes and direction.”

“The acid got me deep into The Beatles’ psych era recordings, bringing imagination into pop,” he remembers with characteristic candour. “That, coupled, with the freedom from conventional arranging afforded by the use of analogue synths, led to this psych/electronic hybrid. I felt suddenly liberated. Put simply, the chemical had ‘rehardwired’ my brain, including my musical tastes and direction.”

‘DCT Dreams’, and its similarly inspired B-side, ‘Treeline’, represent the missing link between The Beatles and the robo-romanticism of John Foxx, Numan et al. This odd little 7″‘s very existence gives weight to the notion that the synth-poppers of the late 70s and early 80s were in fact reconnecting with a British psychedelic tradition that had been tossed aside by punk (John Foxx’s 1983 album The Golden Section would make the link even more explicit).

Did punk have any impact on Nick Nicely? “I was living in a squat in a room over from a punk star, Tyrone from Alternative TV, and I had to apologise to him for the noise. Punk had no part in my influences, apart from that great DIY ethic which led to my self-releasing ‘DCT Dreams’.”

“I was living over from a punk star, and I had to apologise to him for the noise.”

Ah yes – not content with writing, performing and producing his debut single, Laurien also chose to release it via his own Voxette Records imprint, despite entreaties from 4AD and Charisma. He didn’t rest on his laurels when it came to promoting the record, either. “I started to badger [BBC] Radio 1 from my base round the corner in the publishing company, then they started playing it a lot, as did commercial stations, it was ‘record of the week ‘ here and there.”

Nonetheless the single failed to gain any real traction, and so Laurien decided to accept an offer from German label Ariola-Hansa (home to Japan) to re-release it. The deal took an age to finalise, and by the time the A-H edition of ‘DCT Dreams’ came out it was January 1981, and British radio perhaps understandably deemed the song old news, though it did end up clocking up respectable sales and airplay abroad. “It went on to be released across Europe and South America,” says Laurien. “It was heavily playlisted in many countries, making me the highest homegrown earner at the publishing company by a big margin. Particularly good for them, as they kept every penny I earned.”

Nick Nicely’s next single was ‘Hilly Fields (1892)’. It’s his masterpiece, crammed with ideas, and even more so than ‘DCT Dreams’ it seeks to pick up where The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour and Strawberry Fields Forever left off (the song’s title acknowledges this, while also paying tribute to Lewisham’s real life Hilly Fields park). As Laurien would later tell Terrascope magazine, “When Nick Nicely tracks are recorded, suitability for live performance is never a consideration.” This is studio music, impossible music, enabled only by the wonders of multi-tracking.

Nick Nicely’s next single was ‘Hilly Fields (1892)’. It’s his masterpiece, crammed with ideas, and even more so than ‘DCT Dreams’ it seeks to pick up where The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour and Strawberry Fields Forever left off (the song’s title acknowledges this, while also paying tribute to Lewisham’s real life Hilly Fields park). As Laurien would later tell Terrascope magazine, “When Nick Nicely tracks are recorded, suitability for live performance is never a consideration.” This is studio music, impossible music, enabled only by the wonders of multi-tracking.

Following the souring of his relationship with Heath Levy, Laurien demo’d the single at the Hackney home of Geoff Leach, a musician friend whose rudimentary analogue synth had featured on ‘DCT Dreams’, and then recorded it at a professional studio – the 16-track Alvic in Barons Court, London – at his own expense, with a close coterie of friends contributing keyboard, cello and drum parts. An increasingly obsessive re-arranger and post-producer, it took him six months to perfect this one song – “Six months is relatively fast for my stuff,” he says today – and he had to sell all his instruments, then his home studio, and finally assorted household items, to fund the sessions.

“EMI never dropped me, I just sank in the mire and stopped communicating.”

After ditching the original B-side to ‘Hilly Fields’, Laurien and his sidemen manage to record a replacement number in just three days, really a microsecond in Nick Nicely time, and while they were tripping their tits off at that – entitled ’49 Cigars’, it’s a suitably swirling affair, replete with phasers-set-to-stun and disorienting telephone chatter (actually Kissing The Pink’s Nick Whitecross making a call to his girlfriend from the studio). ‘Hilly Fields’ was signed to EMI, but like its predecessor failed to find a foothold in radio playlists or the charts. Nonetheless, it built up an enormous cult following in a short space of time – notable fans include Robert Wyatt, Robyn Hitchcock and XTC’s Andy Partridge, whose psych pastiche project The Dukes Of Stratosphear was directly inspired by Nicely.

‘Hilly Fields (1892)’

EMI continued to fund Laurien’s attempts to record a follow-up to ‘Hilly Fields’ in various cheap studios; these sessions yielded some fine tracks – including ‘Elegant Daze’, his most obviously eighties-sounding song – but he was running out of steam. “I had some long conversations with Trevor Horn about recording,” he remembers, “But, being at a low ebb, I was probably unimpressive and intimidated. EMI never dropped me, I just sank in the mire and stopped communicating.”

Heath Levy had shafted Nick Nicely out of all his earnings, and a long battle with depression and began in earnest. “Grinding poverty crushed the project and my mental state. I was essentially off the rails for a few years. The mid to late 80s were a terrible time and I’m just happy to have survived.”

Heath Levy had shafted Nick Nicely out of all his earnings, and a long battle with depression and began in earnest. “Grinding poverty crushed the project and my mental state. I was essentially off the rails for a few years. The mid to late 80s were a terrible time and I’m just happy to have survived.”

A tenancy buyout in 1988 enable Laurien to buy some new equipment and get back on his feet, personally and artistically. Ever attuned to new avenues of psychedelic exploration, he became involved in putting on illegal acid house parties in ’89 and got caught up in what he calls “the new abstract electronic dance music” – he even breached the national dance charts with some of his own productions in that vein, most notably with Gavin Mills as Citizen Kaned and Psychotropia.

“Doing Acid House was not such a leap from some Nick Nicely stuff like ‘DCT’ and ‘Marlon’,” he reflects. “I’d been working with drum machines since 1980.”

“Grinding poverty crushed the project and my mental state.”

By 1997, Laurien felt ready to record some new Nick Nicely music. One of the songs from this period, the whooshing, washed-out ‘On The Beach’, counts among his finest achievements, a work of refined, psych-pop minimalism whose whiff of the Balearic belies its post-rave provenance.

Interest in Nick Nicely as a “lost legend” mounted further during the 2000s, leading to the release in 2003 of Psychotropia, a collection of his handful of singles and selected demos – mostly sourced from old cassettes and given a fresh lick of paint by the man himself. The Nicely revival was now in full swing, and by 2005 he was being heralded by such luminaries of the US underground as Ariel Pink, John Maus, Gary War and Nite Jewel.

Freshly motivated, Laurien began recording an album of all-new music, Lysergia, in 2007. It has yet to be completed, though a snapshot of the work in progress was issued on limited cassette by California’s Burger Records last year. “I’m in no rush to release Lysergia on other formats,” he says. When I have the music to play to myself that’s 9/10ths of the point. The album continues to grow and improve, and exactly when it comes out seems unimportant to me.

Freshly motivated, Laurien began recording an album of all-new music, Lysergia, in 2007. It has yet to be completed, though a snapshot of the work in progress was issued on limited cassette by California’s Burger Records last year. “I’m in no rush to release Lysergia on other formats,” he says. When I have the music to play to myself that’s 9/10ths of the point. The album continues to grow and improve, and exactly when it comes out seems unimportant to me.

“I’m happy to wait,” he continues. “My unusual and time-consuming system for production seems, so far, to have immunised my work against the lameness that often affects the older artist.”

After making a return to live performance in 2008, as Nick Nicely and The Unlived Lives (featuring members of Bevis Frond and The Damned, among others), in 2010 he collaborated with UNKLE on a track called ‘The Puppeteer’ (the track that didn’t make the album, Where Did The Night Fall, but a demo of found its way onto the web), and was also involved with Amorphous Androgynous’s endearingly unwieldy A Monstrous Psychedelic Bubble Exploding In Your Mind project. Late last year, Captured Tracks released Elegant Daze: 1979-1986, a vinyl compilation similar in content to Psychotropia, but with a few key additions, subtractions and refinements.

As well as continuing to tinker away at Lysergia, the ever-evolving the album that he estimates he has now spent over 1500 hours on, and collaborating with Brooklyn band La Big Vic, Nicely is this year planning to unveil a new version of ‘Hilly Fields’. ‘Hilly Fields (The Mourning)’ will be released on 7″ in May by Fruits de Mer Records, backed with the original version.

And so Nick Nicely’s psychedelic mission continues. “My newest tracks sound good to me. I do share the almost universally accepted prejudice that artists do their best work in their 20s, but with one important caveat…it doesn’t apply to me.”

Kiran Sande