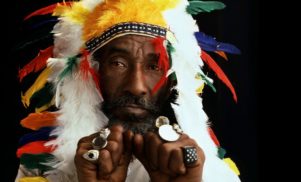

With a prolific career that has already lasted over 50 years, and with a recorded output that shows no sign of slowing down even as he reaches his late seventies, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s voluminous catalogue is not for the fainthearted.

Perry was actively involved in every major shift in style in Jamaican popular music during the 1960s and 70s – from the first stirrings of ska at Studio One, and the brief reign of rock steady, to the startling new sound of reggae (which he helped birth as an independent producer with the Upsetter label) and, of course, his roots reggae heyday at the Black Ark, the tiny home studio in which he conjured pioneering dub techniques and abstract, off-the-wall releases.

Then came the fall, when too much ganja, white rum and political, spiritual and personal upheaval brought a massive meltdown, culminating in the trashing and burning of the Ark. Scratch found himself transformed into a wandering nomad who made music with various degrees of palatability in different parts of the globe, no longer in full command as a record producer, but in partnership instead with different disciples (who did most of the construction and execution, leaving Perry to warble freely on the mic).

With this endless stream of music to consider, plenty of true treasures can get lost in the shuffle – especially when the back catalogue has been plundered, repackaged and retitled countless times, often for releases of dubious provenance. What follows are 10 of the most noteworthy Perry releases you may have missed – 10 worthy nuggets to seek out and savour.

Lee Perry

Old For New 7″ 45

(Rolando & Powie [JA] 1962/R&B 45 [UK] 1963)

Recorded shortly after Perry’s arrival in Kingston, ‘Old For New’ is the sound of the man at the very start of his musical journey, during a time when he performed various supporting roles at Studio One, such as talent scout, sound system spy, auditions assistant, and general dogsbody, doing whatever label boss Clement ‘Sir Coxsone’ Dodd deemed necessary. Cut on a bouncing rhythm in the nascent ska form, with a hint of the rhythm and blues that proceeded it, the track is introduced by a plaintive harmonica line and is punctuated mid-way through by an evocative saxophone solo from Roland Alphonso; vocally, there is Perry himself earnestly relating a Jamaican proverb, full of folk wisdom and with plenty of promise, anticipating the greatness to come.

There’s a touch of innocence about the tune, yet Perry sounds older than his years here, his words already coded and cryptic. He’s not yet fully in the driving seat, but there is a sense that the song is very much his own, and different from what his peers were creating. In short, this is a unique, dignified and portentous beginning to what would be a very long, fruitful, and ultimately individual career.

Prince Buster (and Lee Perry)

Johnny Cool Parts 1 and 2 7″ 45

(Olive Blossom [JA] 1966/FAB [UK] 1967)

Perry worked at Studio One for five years, from 1961-66. During that time, he recorded some three dozen or so songs as a vocalist, and was involved in a lot of uncredited production input, working closely with keyboardist Jackie Mittoo behind the scenes. Tired of not being credited properly, nor being given proper financial recompense for his work, Perry broke away in 1966 to forge a series of short-lived partnerships, one of the most noteworthy of which was with Prince Buster, who he’d bonded with on arrival in Kingston; Buster once famously rescued Perry during a sound system battle, and the two shared a close camaraderie in the downtown Kingston wild spots, with Perry eventually taking over Buster’s Record Shack at 36 Charles Street.

On the great rock steady track ‘Johnny Cool,’ Perry’s playfully supportive role has him cast as a perfect foil to Buster’s bravado, and even if the subject matter of Part 1 is serious (namely, the ‘rude boy’ crime wave that saw wanton violence and rape meted out to innocent ghetto dwellers by street thugs), both sides of this single are a sheer musical delight, the rousing horn fanfare a thrilling counterpart to Lyn Taitt’s picking guitar line.

Burt Walters & The Upsetters

Evol Yenoh 7″ 45

(Upsetter blank [JA] 1968)

After leaving Studio One, Perry forged short-lived partnerships with Prince Buster, Clancy Eccles, Joe Gibbs and Linford Anderson, among others, the partnerships stemming from the lack of ready finance that would eventually enable him to be a fully-fledged independent producer. Working regularly at WIRL studio, he formed the Upset label with Anderson and trainee engineer Barrington Lambert, but then branched out on his own, following the success of ‘People Funny Boy,’ a swipe at Gibbs with a crying baby, lifted from a sound effects record.

Burt Walters’ ‘Honey Love’ is one of the earliest releases for Perry’s Upsetter label (issued on blanks, since he had no money to cover printing costs), and although the A-side is an unremarkable cover of a Drifters song by an unknown adenoidal crooner, the B-side is something else entirely, being the same song with the vocal played backwards. It’s a sure sign of the Upsetter’s need to always experiment, to try something different than the rest, and the startling nature of the result makes it easy to understand why Trojan Records would substitute a more standard instrumental on the flip when they issued ‘Honey Love’ in the UK.

The Upsetters

Water Pump 7-inch 45

(Justice League [JA]/Upsetter [UK] 1972)

After working with the Wailers at Randy’s studio on the seminal recordings that would prepare them for the international stardom they would achieve upon signing with Island Records, Perry settled into a long period of residence at Dynamic Sound (re-named when WIRL was rebuilt), then the Caribbean’s best-equipped recording facility, where he acted as one of the in-house producers, trading production and engineering work in exchange for free studio time; for dub version B-sides, much of his output was being crafted at King Tubby’s front-room studio in Waterhouse, since Perry’s own Black Ark studio would not be operational until the end of 1973.

‘Water Pump’ is a very rude ditty delivered by Perry during this phase, an even if the song is nothing but light-hearted sleaze, the lyrics are so clever and related in such an singular manner as to make this classic Scratch; the innuendo and sexual bragging is pretty hilarious, and not approaching anything like the kind of in-your-face offensiveness of his pornographic post-Ark works. Listen carefully to the end of the version B-side and you’ll hear a strange splice, with sped-up laughter, another moment of Upsetter wizardry immortalised forever on wax.

The Upsetters

Cow Thief Skank/7¾ Skank 7″ 45

(Justice League [JA]/Upsetter [UK] 1973)

Even before he had a studio of his own at his disposal, Lee Perry took every available opportunity to experiment with the limits of recorded sound. ‘Cow Thief Skank’ and its dissociated version, ‘7¾ Skank’ are a good case in point. To fully understand these tracks you need to be familiar with Ernie Smith’s ‘Pitta Patta’ (and the Upsetters’ re-cut of it, ‘Musical Transplant’), the Staple Singers’ ‘This Old Town (People In This Town),’ the Inspirations’ ‘Stand By Me,’ and the Carltons’ ‘Better Days,’ since each of those tracks are part of it.

On the A-side, you can almost forget this fact, as Perry and deejay Charlie Ace berate their peer, Niney the Observer, for thieving a black-and-white cow while sporting inferior footwear; hit the B-side and the cut-up experiment is laid bare, chopping and changing between ‘Musical Transplant’ and ‘Better Days’ after having gotten through snatches of ‘This Old Town’ and ‘Stand By Me.’ No one else in Jamaica was making anything even remotely close like this at the time, making it another one-off piece of Perry creativity.

Max Romeo

Revelation Time LP (aka Warning Warning!, aka Open The Iron Gate

(Tropical Sound Tracks [JA] 1975/Jam Sounds [JA] 1977/Surface [CA] 1977/Different (UK) 1978/United Artists (US) 1978)

Max Romeo and Lee Perry had strong links from the early 1970s, when they collaborated on songs such as ‘Public Enemy Number One’ (about Satan’s many guises) and ‘Rasta Bandwagon’ (about non-black citizens becoming involved in the faith). By the time Perry opened the Black Ark, Romeo had entirely reinvented himself as a singer of social protest songs, and the single ‘Revelation Time,’ recorded at the Ark for producer Pete Weston, spoke of police brutality, capital punishment and Jamaica’s shift towards Socialism.

Shortly thereafter, under the direction of Clive Hunt and Geoffrey Chung of the Now Generation, the Revelation Time album was put together, largely at the Ark with Perry at the controls, yielding what is probably the first reggae concept album, a strong preface to the War In A Babylon set Romeo and Perry would create the following year; outstanding tracks include ‘Blood Of The Prophet’ (seemingly about the reported death of Haile Selassie), and repatriation number ‘Open The Iron Gate,’ both of which are followed by great dub workouts on the original album release. ‘Three Blind Mice,’ an earlier single Romeo voiced for Perry, is also included for good measure.

The Skatalites

The Legendary Skatalites LP (aka African Roots, aka Rebirth)

(Jam Sounds [JA] 1976/United Artists [US] 1978)

Another oddity from the same period as Revelation Time, brought to the outside world through Clive Hunt’s connections and issued in different forms under different titles over the years, The Legendary Skatalites album dates from a time when the Skatalites had been dormant as a group for over a decade, but its players began working together again after bassist Lloyd Brevett had initiated a project with niyabinghi drum troupe Ras Michael and the Sons of Negus that went awry before completion.

Most of the rhythm tracks for the album were laid at the Black Ark with Lee Perry, though later overdubs took place at Aquarius and Harry J. Later, the entire thing was mixed down at King Tubby’s studio, and the US edition on United Artists benefitted from Tom Moulton’s ears. At the core of the album is its Black Ark bedrock, courtesy of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, which you can hear most vividly on the niyabinghi tracks like ‘Candle Light’ and ‘Jumbo Malt,’ the latter a killer cut of Brevett’s ‘Starlight’ single. Its dub companion, Herb Dub Collie Dub (aka Heroes Of Reggae In Dub) is equally compelling.

Ras Michael and the Songs of Negus

Love Thy Neighbour LP

(Jah Life International [US] 1979/Live and Learn [US] 1984)

One of the most stunning albums to emerge from the latter phase of the Black Ark, Love Thy Neighbour is another highly intriguing record. Though parts of it were cut at Dynamic Sounds with engineer Jerome Franciscque, and at Channel One under guitarist Earl ‘Chinna’ Smith’s direction, the album’s overall sound is again clearly the product of the overburdened mind of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, who was then succumbing to various pressures, and on the brink of psychic collapse.

The whole affair sounds heavily stoned, the drummers making a joyful niyabinghi noise, with Hux Brown and Chinna adding an air of jazzy blues, while Ras Michael delivers drawling lead vocals in praise of the Most High, critical of Babylonian excesses. ‘Don’t Sell Daddy No Whiskey’ sets the tone with a slowly unfolding warning of the perils of alcohol misuse, while ‘Times Is Drawing Nigh’ is a niyabinghi recasting of ‘Norwegian Wood.’ The original album release on Jah Life has three songs not present on subsequent editions, namely the chilling slavery tale ‘Long Time Ago,’ the mournful ‘Do You Know’ and the rousing ‘Jesus Christus Is The King,’ but either edition is definitely worth tracking down, being representative of the extreme heights of the Black Ark, teetering on the edge of collapse.

Lee Perry

Jah Road Block 12″ 45

(Joe Gibbs Music [US] 1982)

In late 1979, Perry shut the doors of the Black Ark after coming into conflict with those who were working there, as well as a radical Rastafari subgroup known as the Niyabinghi Theocracy, who had close interaction with Perry during the late 1970s. He trashed the place, throwing much of the equipment into a septic tank, and it gradually fell into disrepair. With no functional studio of his own at his disposal, Perry drifted to New York to work with white reggae bands the Terrorists and the Majestics, cutting an album at Dynamics with the latter on his return to Kingston.

Then came this peculiar 12-inch, which Perry recorded at Joe Gibbs’ studio with engineer Errol Thompson; ‘Jah Road Block’ reworked the hymn ‘Daniel Saw The Stone’ but in the manner of Pipecock Jackxon-era Scratch, with references to ‘Allah-Jah’ and Taurus the Bull, as his alternate cosmology came into play. The throbbing B-side, ‘Ala Jah,’ has a pleasant alto sax melody from Dean Fraser and spongy keyboards from Franklyn ‘Bubbler’ Waul, helping to ground the tune in traditional reggae, even as Perry’s vocal strays further and further from our known reality. Check Howard Johnson’s Deep Roots Music to see Perry and ET at work on the tune.

Lee Perry

‘Babylon A Fall’

(Recorded late 1970s, issued on Soundz Of The Hotline, Heartbeat CD [US/EU] 1992)

Perry’s post-Ark work has been distinctly uneven. There have been some very choice high points, mostly courtesy of collaborative work with Adrian Sherwood and Mad Professor, but many low points too. Diehard Perry fans often hearken for his Jamaican recordings of the 1970s and 60s, and archivists occasionally unearth some real gems. ‘Babylon A Fall’ is one such number, and unlike the Watty Burnett track of the same name, this anti-papal epic was probably voiced in late 1978, since it makes reference to the televised burial of Pope Paul VI, who died in August that year.

The rhythm was also used for Junior Murvin’s chilling ‘I Was Appointed,’ but the version of that song using this same rhythm was abandoned at the time, and a more complex rhythm used instead for the cut that appeared on Junior’s debut album; here, the sparse and eerie backing allows Perry good space for a double-tracked conversation with himself about the wrongdoings of Babylon, the multi-tracking a later hallmark of his post-Ark canon. Despite being obviously unfinished, the song remains as compelling as some of all-time greats, and is definitely worth getting to know if it’s not in your collection already.