The history of field recording is central to the development of electronic music, with artists from Eno to Scanner to Burial drawing on its strategies to create distinctive soundworlds. Lawrence English – boss of the long-running Room40 imprint and the man behind this year’s exceptional Wilderness of Mirrors album – presents a beginner’s guide to the discipline, including a rundown of crucial recent releases.

In Peter Szendy’s provocative book Listening, he presents two related questions: “Can one make a listening listened to? Can I transmit my listening, unique as it is?”

It’s these questions that have occupied my thinking a great deal over the past few years. This preoccupation has resonated through much of my work, specifically though my practice of field recording. More importantly, it has provided me with the opportunity to think critically about what it is that makes field recordings affecting, meaningful and ultimately creative. Why, for example, is it some these types of recordings move us, and others simply don’t?

It’s not that long ago when recordists and researchers working with sound thought of it as a mechanism through which objectivity could be transmitted. One needs to listen no further than early ethnomusicology and mid-century wildlife recording for examples of this attitude. The pretence to being objective brought with it an inferred negation of agency, that somehow the recordist was simply capturing moments of the real when they started the tape rolling. The idea of objective recording in the field, thankfully now problematised and rejected, still lingers though like a spectre haunting the ways many listeners consider recordings. It is as if, somehow, because of where they are recorded they are true. The issue for anyone who undertakes field recording as part of their practice is to recognise that agency and ultimately a kind of creative subjective listening is vital if the work is to transmit, as Szendy puts it, the listener’s listening.

But what is field recording? And moreover why has it become a substantial presence in the contemporary sound ecologies? Merely two decades ago it was a somewhat uncharted realm lacking vigorous and pluralistic investigations. It’s these questions and a few more I am seeking to consider here. I should at this point say that what follows is by no means an exhaustive survey of field recording artistry or a bible of practices. It is perhaps more a sketch or mud map from which you can cut your own pathway into the field should that appeal.

Chris Watson

To Listen Is Not Always To Hear

Recognising the start of something isn’t always as straightforward as it seems, hence the persistence of hindsight. For example the reasons of how I became interested in field recording, took root not from recording, but rather, listening. When I was a young boy, I would go to an abandoned part of the Port of Brisbane, which has since turned into a string of lifeless condos. Back in the early 1980s, though this area was a wasteland of sorts, a refuge for animals and birds, and a favourite haunt of my father who would take my brother and I there for all kinds of adventuring. In this area was a particular species of bird, the Reed Warbler. It sounded incredible, like a modular synthesizer on steroids. Easy to listen for, but due to the bird’s size, colour and penchant for hiding in the reeds, it was very difficult to see.

To combat this predicament, my father told me first to close my eyes and then to listen, to locate the bird with my ears and then open my eyes and look for it. Not that I thought about it at the time, but this is my first memory of actually listening. When I say listening, I mean focusing on events in space and time, excluding as much sonic material (if not more), than I actually chose to listen to from that given horizon of listening. The reason I mention this story is that, in many ways, that process of listening for the bird, of focusing in and on sound in a particular space and time, consciously drawing out particular elements in preference to others is, for me at least, at the very core of what field recording is about.

Broadly, field recording can be summarised as a diverse set of practices concerned with recording sound from atmospheric, hydrophonic, geophonic, electro-magnetic and other sources. It is a sprawling pursuit, but resolves toward an interest in creating and transmitting an impression of audition in time. As field recording, in its contemporary phase, has come to be acknowledged more widely, there has been a rising tide of publications from artists scattered across the globe. These artists are primarily investigating the potentials of environments, acoustic phenomena and all manner of other auditory situations in which they find themselves. This growth in activity owes much to specific technological and economic shifts, which have increased access, exposure and opportunity to participate (both as creator and audience).

What unites the more successful of these publications is the intensity of perspective and impression they reveal to an audience. The most affecting recordings offer a focus that lays beyond the everyday listening we experience. They reveal a depth or presence that transforms the moment of recording into something hyperreal, to borrow Baudrillard’s term, that can be meaningfully engaged with by other listeners at a future times and in different places.

To be merely exotic or unusual is not enough to make a powerful field recording. Whereas a curiosity for the atypical might have pervaded throughout earlier parts of the 20th century, the conditions of the digital age, travel opportunities and the abundance of access to just about anything, makes the notion of the exotic problematic at best and just plain toxic at worst. Today, we seek new perspectives and exposures that refocus sometimes even the most commonplace experiences into profound and provocative listening situations.

Walter Ruttmann

Echoes of Phonography

It’s easy to forget that the history of sonic reproduction stretches back only just over a century. Thomas Edison’s phonograph, the precursor to all modern home playback systems and the first widely available reproduction device, surfaced only in the fading moments of the 19th century. Its effect was seminal, affecting the ways we understood listening. As Douglas Kahn points out in Noise Water Meat, the phonograph heard everything, it did not participate in the subjective, psychological filtering of our ears. This recognition was a crucial awakening and a moment that has shaped subsequent thinking about audition in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The phonograph’s patent application listed a curious variety of uses, including the recording of the last dying words of family members, but it was to be the reproducibility of music, that would indelibly stain phonography into the fabric of popular culture. Not everyone was so wed to the phonograph as just the first musical bootlegging device though. The earliest recorded non-anthropic sound came care of a young Ludwig Koch who recorded the Common Sharma, a bird, with his father’s wax cylinder recorder in 1889. Koch, still a child at the time, would go on to become one of the earliest wildlife recordists and a highly regarded broadcaster. He was also responsible for creating a range of recording techniques that were revolutionary in their day.

As the 20th century took hold, the subjects of recordings expanded within anthropic circles also, spilling out of the concert hall and into the field. Ethnomusicologists such as Hugh Tracey and Alan and John Lomax, as well as Australia’s Alice Marshall Moyle and Japan’s Kurosawa Takatomo, all undertook extensive fieldwork recording musical traditions and languages, many of which no longer exist. Indeed the earliest use of the term field recording is aligned with the practices of these researchers and archivists.

What marks these individuals so very of their time though, was their thinking that the recordings made could be effectively objective and real. These notions, like those more broadly concerned with ethnography, have thankfully transitioned to more subjective understanding of the processes of recording. It’s this shift, however, that marks an important transition into contemporary understandings of field recording.

China’s Yan Jun addresses this recognition of subjectivity through much of his work. “There is no such thing as documenting a reality,” he tells me, “There is no divide between documenting and creating. The point is I don’t build dreams neither by field recording nor by playing my electronics instruments or computer. To choose equipments, choose position and push record button are acts of composing. Tiny meaningless noises can be a beautiful composition. To summarise I can use this equation – I push the record button = someone making a musique concréte piece = Bach.”

Spanish sound artist Francisco Lopez also argues against the notions of documentary objectivity. His work, which centres around the transformation of reality though sound materials recorded in the field, pushes a reductive approach to listening, one informed by the theories of phenomenologist Edmund Hussurl and French musique concréte pioneer and Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM) leader Pierre Schaeffer.

“The move away from the representational and documentative does not essentially depend on transformation of sounds but fundamentally on the listening mode we carry out,” Lopez says. “A ‘reduced’ Husserlian/Schaefferian one opens, in my opinion, the gates to a different world that tends to be self-referential and thus more open and free. I use these materials as sound-in-itself, as opposed to the representational approach. That is, as phenomenological substance, both in their manifestation as originally recorded and in the typically long process of evolution that takes place in the making of my compositions.”

In 1983, Michel Chion wrote: “Reduced listening is the attitude which consists in listening to the sound for its own sake, as a sound object by removing its real or supposed source and the meaning it may convey.” The theory originally developed by Schaeffer marks out a discrete stream of activity within contemporary field recording, one that is very much about the absolute value of the sound. This idea, of sound-in-itself and acousmatic listening, has become a battleground of late with a number of academics and cultural critics problematising the idea, the most vocal of whom is Seth Kim Cohen, whose book In The Blink Of An Ear delves into the issue with great ferocity.

Whilst not directly entrenched in the ideals of acousmatic listening, some transgressive examples of field recording oriented compositions do dot the early 20th century – the most powerful perhaps being Walter Ruttmann’s Weekend. Weekend was created using early film equipment that offered a capacity for sound recording. The piece, created for German radio, used visual montage methods and edits but concerned itself merely with sound, rejecting the visual in favour of the audio. This radical shift in focus, the reduction to sound and Ruttmann’s aesthetic focus on cutting and splicing in some respects pre-empts musique concréte and John Cage’s tape experiments.

The possibility for most artists to make recordings using portable, high fidelity equipment only arrived with the introduction of magnetic tape half way through the 20th century. It’s here we find the beginnings of how it is we consider field recording today.

Luc Ferrari (via Kim Cohen)

Luc Ferrari’s open listening

If there’s one piece that acts as a prelude to many of the field recording practices of today, Luc Ferrari’s Presque Rien No. 1 (Le Lever Du Jour Au Bord De La Mer) might be the most fitting anchor point in the 20th century. Recorded in Vela Luka, a small fishing village located in present day Croatia, the piece was offered as both provocation and antidote to the methodological concerns maintained by musique concréte and its architect Schaeffer. The title, Presque Rien translates to ‘Almost Nothing’, which references how the recordings were treated (that is ‘almost nothing’ was done to them), is the first expression of its kind. It is markedly different to the work of Ferrari’s GRM contemporaries because it refused the transformation of concréte sound materials in favour of allowing the recordings to self-resonate.

Ferrari was one of a number of composers associated with GRM, the seminal hothouse of experimental compositional practices in France. A loveable troublemaker, his decision to test the methods commanding GRM’s direction uncovered a powerful new way of approaching work he called Anecdotal Music. This idea focused on a kind of open listening to environment, in which the events of any given space can reveal meaning should the listener be open to it. It invited a focus on the importance of the listener’s listening whilst recording as a valuable creative tool.

More importantly, Ferrari recognised the opportunity for a departure from the Schaefferian ideals of musique concréte. Ferrari stated he “thought it had to be possible to retain absolutely the structural qualities of the old musique concréte without throwing away the content of reality of the material it had originally. It had to be possible to make music and to bring into relation together the shreds of reality in order to tell stories.”

What’s most remarkable about Presque Rein today is it still carries with it a great sense of presence. It is not necessarily dramatic or affected, rather it is an incredibly powerful example of listening and the transmission of that listening. This listening is, for me at least, at the very core of successful field recordings. I don’t sense I am alone with this proposition though; David Toop, arguably one of the great modern contemplators of sound, weighs in.

“Field recording,” he explains of his introduction to the practice, “was a natural consequence of listening, or becoming more fully aware of listening. At first there was a novelty to making recordings of environments. In the late 1960s I’d bought a bargain bin record called Sounds of the Serengeti and was fascinated by its atmospheres and the structures I was hearing – two bou bou shrikes in an asynchronous call-and-response, for example. When I was given a little mono cassette recorder in 1970 I used it to record music first of all, but the next obvious use was to record animals, birds and water.

“On one occasion I recorded flute on Dartmoor, hanging the microphone on a wire fence. Later, when I listened, I realised that the flute was only a small part of the recording. The sounds of the fence rattling in the wind, sheep crying on the moors and my flute being shredded into tatters by the wind had a profound effect on me, shifting me from the centre of the universe and placing me within an ecology on sound. In this sense field recording gave me a new understanding of listening: the point of audition could change constantly; the sound field is in a constant state of dispersal. That realisation continues to have a deep effect on my conception of music and listening.”

Jana Winderen

A Plurality Of The Ears

Since Ferrari’s early offerings, several generations of artists have sought to uncover the affective sound worlds that persist in and around us. As the practices have grown, so too has the theoretical and methodological ways in which the work can be understood. As with all active practices, there’s been a continued growth in the way artists both undertake and position the work. Increasingly field recordings are finding the ways into gallery spaces amongst other, once foreign, settings. Developing a lens of concept (to use a visual metaphor), through which they define their recordings, many artists are exploring powerful new approaches to framing, positioning, scale, proportion, richness of spectrum and editing which give the recordings a profoundly unique, artist-led positioning.

South African artist James Webb is one such artist working in this way, addressing this idea of the positioning of sound with his various installation works including a recent piece The Nameless Threshold. “My work with field recordings is about invocation not documentation,” he explains. “The Nameless Threshold uses recordings of dogs from the security forces and canine units of the South African Police Force. These are visceral sounds, heavily associated with control and fear. I spent a long time researching the canine aspects of the armed and security forces and did many studies towards the final installation.

“I didn’t want the work to be a document of my process or a blunt political history lesson. I wanted to place the audience in a particular space and have them experience something directly. This would allow them to interpret that experience in relation to their own ideas.”

American sound artist Stephen Vitiello confirms that concept plays a central role for his practice also, but goes further, arguing context can shape both understanding and the actual listening to, of sound. “For me, with my work,” says Vitiello, “part of the difference definitely is conceptual – how I approach the idea behind the recording and the context in which it is played back. It also has to do with narrative and ways that I find a series of events that are captured in time. I might consider one recording of a marsh a document, where there is a nice sense of the place, frogs are croaking, insects are sounding but nothing (to my ears) remarkable jumps out. Then, there might be a piece I put more claim to as compositional, even if it is about my discovering that composition – the same marsh but an owl flies by and then another sort of whooshing sound is heard, the warning signal of a white tailed deer and then the frogs naturally quiet down and voices are heard in the distance.”

Attentiveness to dramaturgy is another theme that recurs in many of the more compelling field recordings published over the past two decades. This dramaturgy can exist in micro-occurrences, subtle aspects that when attuned to, can create a depth of activity that invites repeated visitation of the recording.

Australian field recordist and experimental musician Robert Curgenven is explicitly conscious of how dramaturgy is expressed in his recordings. “Events across a durational plane give rise to tensions, declensions and the dramaturgical developments that can be read as a kind of theatre,” he explains, “the emergence of a dramaturgical framework within the field of action. Even ‘non-action’ becomes a kind of action, absence is informed by presence, drawing on a theatrical tradition as broad as Beckett, Sartre, Artaud, whilst drawing broadly on Tarkovsky’s notion of ‘time pressure’. Time pressure also has the potential to cross-over into an application through ‘sound pressure’, which itself can be a product of meteorological shifts in micro, or even macro, climates over time which produces its own kind of extant dramaturgy.”

It’s through these kinds of multilayered dramaturgical approaches, in the broadest sense from the executions of tension and release (performed so elegantly by artists such as Francisco Lopez) through to more linear sound-storytelling, that structure, editing and narrative plays a role.

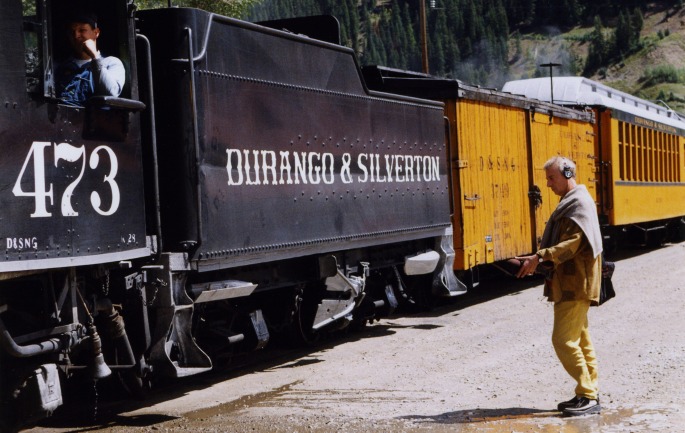

Of all the artists presently engaged in field recording, it’s perhaps Chris Watson – a founder member of Sheffield experimental figureheads Cabaret Voltaire – who has been able to capture the widest audience with his work. A master craftsman, whose recordings maintain a distinctly lyrical quality, and a gifted storyteller, his records of the past 15 years have both captivated and inspired a generation of listeners and artists. His edition El Tren Fantasma is a perfect expression of how a dramatically informed narrative thematic may perform within field recording.

“Both lyrical and narrative works interest me,” Watson confirms. “Spending time in places, for myself anyway, I was interested in how a place changes over time. The timescale involved could be enormous or fractional, and I wanted to represent that, so I started on this series of time compressions if you like, which Weather Report was my first attempt at doing that. Recently with El Tren Fantasma, I compressed a five-week train journey quite literally into the tracks on the CD. So it was a journey and that’s relatively simple, but I find it a very good way for me to work.

“That has something to do with how I started out, working with soundscapes and soundtracks,” he continues. I was learning in a television post-production environment where it’s an obvious film narrative, a linear narrative. So I learnt this art, or the craft of this area if you like, through my time there and some of that has stuck with me right through to today.”

Not all artists share a desire to create narrative, though. There are many who address philosophical and phenomenological concerns too, seeking to manifest them audibly. One such investigator, who is perhaps best recognised for this audible (but not always) expression of phenomena is Yokohama-based artist Toshiya Tsunoda. For well over a decade, Tsunoda has been investigating sounds that exist beyond our usual scope of experience – his recordings of very small spaces, hidden micro-environments and other uncommon acoustic events have marked out a distinctive place for him in the contemporary landscape. A place where method and phenomena, plays as much of a role as the recording itself.

“I want to ask these questions,” says Tsunoda, “what is ‘place’ or ‘space’? What, where and how is the relationship between our consciousness and bodily experience with ‘place’. This remains the key question involved in my recording work. I am not interesting in this kind of ‘strange sound’ that is sometimes found in this area in terms of my artwork practise.”

Beyond dimensions of place and space, another major consideration for field recording is that of time. Time is relational with both listening and recording. Sound is comprehended through duration, from split seconds onwards and the ability to create a field recording is tangled in a web of time; before, during and after it is completed.

“For me,” explains American pioneer Douglas Quin, “field recording is part of my compositional process and being present in time and space. There is always a fair amount of planning and preparation – anticipation time. This is followed by the actual experience of getting into the field, whether it is your backyard or at the ends of the earth. In this, I try to devote prolonged periods to being in one region or area: days, if not weeks or months. In this way, I can get in sync with the rhythms and timing patterns that are unique and distinct features of place. I learned a lot from Albert Mayr in this regard.”

“Finally, in post-production, as it were, that encapsulated temporal framing within the recordings themselves articulates a different sense of time. Over the years, I have also found that when I listen back to recordings made years earlier that my memories of the recording change. Sometimes, I will rediscover a particularly beautiful recording that I had dismissed or not paid much attention to. At other times, something that I thought was really good, does not really stand the test of critical listening. In that, I realise my impressions are at times coloured by my other senses: it was a warm morning, a lovely scene or setting; the earthy smell of a rainforest stood out. The studio experience of dissociated place listening leaves me with just the sound.”

Jana Winderen echoes Quin’s considerations of time, suggesting that listening beyond anthropic precepts of time is a crucial factor in some areas of field recording.

“I am considering time,” she confirms. “It is an important element of course, you can not say something in too short a time. There are a lot of cycles, changes and different acoustic environments, and all that has to do with time. Many species also uses tone changes in repetition in their sound communication over time.

“You have to spend time. It takes time to listen in a focused way and the way I work, there’s not any point if I am not listening carefully. For example when I hear a new species of fish, I will move to get closer and I will go and ask questions to local people, then go to the same place and so on. Also it takes time to get focused, to start recognising the details.”

Like any medium, the ways in which artists approach the potentials of their expression are diverse to say the least. What does emerge from this diversity of practice is a set of themes or commonalities that seem to transgress individual interest. Ultimately, it’s the desire for compelling listening experiences and moreover the desire to transit these unique listenings that drives many contemporary field recording artists. These listenings are shaped in time, reflecting a range of interests that flow from the scientific, to the theatrical, to the narrative and beyond.

Lawrence English

Toward A Relational Listening

Not all field recordings are affecting. Anyone who has probed the seemingly endless digital archives of field recordists out there will be struck by just how utterly unremarkable a great deal of the recordings are. Now, to be fair, it’s not so much the recordings that are unremarkable, it’s our relationship to them. Some recordings are just for ourselves, they don’t need to be shared or published, they are there for us to recognise some personal memory, a place, a feeling or an individual moment that was somehow best immortalised in sound. I know a great many recordings I have made function purely in this way. They are for me and only make sense to me.

Another common reason why some field recordings fail to convey the intentions of the recorder comes down to a disconnection between the two sets of ears at play during the field recording. These two listenings, that of the human organic ear and the prosthetic ear of the microphone is what allows a field recording its capacity to transit the listening of the artist. Both ears though operate within different horizons of listening. United in place and time, these horizons are shaped by the potential of their listening devices.

The first horizon of listening is that of the organic ear. It’s an internal psychological listening and it’s here we create our listening to place. We actively prioritise certain elements and eschew others, an example is that right now as you read this you are actively filtering a whole range of sounds from your listening, take ten seconds to reconnect with the sounds around you. That humming air conditioner, the television on downstairs, the traffic outside, those shoes connecting with the pavement nearby. Our ears are as good filters as they are listening devices, perhaps even better. This horizon is innately creative and agentive in that we shape and contour the impressions of place as a fluid and ongoing happening.

The second horizon that occurs during field recording is an external, technological horizon of listening manifest by the other set of ears, the microphone. If we are to transmit our listening, as Szendy suggested in his earlier provocations, we need a translation device, a conduit for the listening to be transmitted. Unlike the organic ear, this prosthetic ear of the microphone has no psychological capacity shaping the listening. It is, as Francisco Lopez once put it to me, ‘a non-cognitive listening device’. The microphone’s horizon of listening is shaped by its technical capacities and maintains an altogether different ability for creating an impression of place.

Therefore it’s up to us, as recorders of our listening, to bring these two horizons into some kind of alignment. The aim being to bring the two horizons together and as wholly overlapped as possible. I call this theory relational listening, because what I seek through my field recording is a relational condition between my listening within a given horizon and that of the microphones. To me, a successful field recordist is one who can transmit something of themselves in a particular place/time and that something is their listening. I’d argue that if listening is central to the success or failure of a field recording and this practice is to be part of a canon of sound arts, then surely there needs to be an agentive, creative mode of listening. Relational listening is one place where this creative capacity might be found.

It’s probably fair to say that for the first time in human history, ears are beginning to play a more central role in the way we understand, explore and conceive the world around us. The ability of reproduction and the chance to revisit certain sonic phenomena has played a huge role in this. With specific reference to field recording, we’re now witnessing major cultural institutions such as the Louvre presenting installation works comprised entirely of field recordings, labels have been established entirely dedicated to these practices and countless online resources grow daily. There can be little question then that as a creative practice field recording has come sharply into relief of late, recognition perhaps of the profound and utterly affecting nature of the sounds (and listenings) contained within the recordings.

__________

11 Personal Field Recording Highlights Of The Recent Past

Douglas Quin – Antarctica

Daniel Menche – Raw Recordings Series (Volume 1)

Alvin Lucier – Sferics

Jana Winderen – The Noisiest Guys On The Planet

Jeph Jerman – Lithiary

Tenniscoats – Finnish Karaoke Cassette

David Toop – Lost Shadows: In Defence of the Soul: Yanomami Shamanism, Songs, Ritual 1978

Chris Watson – Stepping Into The Dark

Toshiya Tsunoda – Pieces Of Air

Geir Jenssen – Stromboli

Francisco Lopez – La Selva