I don’t remember the first time I heard ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’, but I do remember hearing it a lot as a child.

Hearing that song at the annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. marches in early January — which I hated because it was always too cold and always too long — was as about as inevitable as seeing scores of black fraternities and sororities proudly marching down the route with pride as bright and warm as the bell of Miles Davis’ trumpet. In 2009, I remember witnessing, with the world, Rev. Joseph E. Lowery using parts of what has been referred to as the “Black American National Anthem” during Barack Obama’s inauguration. Most frequently, I remember hearing ‘Lift Every Voice’ in church – which I hated because it was always too hot and always too long, and always evangelizing something I was very skeptical of believing. It was in the Baptist church specifically, the ones where it’s so spirited and lively that the walls dance and shimmy like a Harlem Renaissance painting. In essence, ‘Lift Every Voice’ is a gospel number, and to be very accurate, a Negro spiritual, coalescing civil rights and the presence of faith.

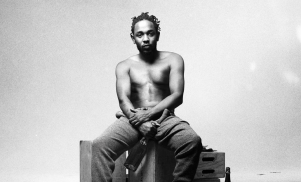

A year after Kendrick Lamar’s complicated magnum opus To Pimp a Butterfly, its apex and focal point remains ‘Alright’, a song that reminds me of ‘Lift Every Voice’ and best represents the robust political and pop cultural force Kendrick has become in the 12 months since its release. The Pharrell-produced track has picked up a few awards, sure, but it has also become a protest song for the millennial generation, hollered out at marches and demonstrations against the original American sin: white supremacy. ‘Alright’, like its graying progenitor ‘Lift Every Voice’, seems destined to live forever, or at least until Donald Trump escorts us into our final days on Earth. “We gon’ be alright” is a slogan for anyone who feels downtrodden, whether or not you believe the mantra to be true, and it’s the album’s most accessible entry point into its themes of political resilience.

Twelve months on, To Pimp a Butterfly is still powerful in its confrontation of issues currently fizzling through American political discourse. It feels like a lightning rod at a time when America is at its most polarized since its citizens’ antithetical ideologies led to an actual war. You could make the case that the majority of rap records are inherently political; the personal is political, after all. But on To Pimp a Butterfly, Lamar used many different voices to grapple with police brutality, gang violence, the golden rule, mental health, colorism within his community, Compton and every place like it.

Lamar wasn’t just telling his story, he was telling a wealth of stories – from the ugly hoodrat archetype (‘For Free?’) to the need for self-love (‘i’) in the face of self-hate (‘u’), to police brutality and violence within the community (‘The Blacker The Berry’). The latter song divided listeners who criticised his respectability politics, but Lamar’s chief concern isn’t to place a higher value on the lives of people who carry themselves a certain way. As he told MTV News around the album’s release, he’s not speaking to the community or even speaking of the community: “I am the community.”

“Lamar has become a messianic figure, taking his cue from the message his mother leaves him at the end of good kid, m.A.A.d city“

His music and message have since then infiltrated the public and political consciousness in a big way. In December, President Obama went on record to crown ‘How Much a Dollar Cost’ his favorite song of 2015. In January, it was revealed Lamar and a few friends went to Washington D.C. to visit the president – a moment that played out the fantasy of To Pimp a Butterfly’s album artwork, in which the rapper and his crew crack champagne bottles on the White House lawn. After his meeting with the President, Lamar parlayed his experience into a public service announcement for the National Mentoring Partnership, underlining his commitment to community.

For many artists, this would have been enough. Kendrick, however, wasn’t finished confirming his greatness. In the thick of the To Pimp a Butterfly album cycle, Lamar began to sneak unheard tracks not featured on the album into his live performances; these rebellions against music industry norms came across as powerful moments of personal expression and defiance. When he performed an unreleased, unknown track for the Colbert Report’s final musical performance, he was breaking free from the constraints faced by major label rap artists. When he performed in shackles and prison denim at the Grammys, he was becoming the kind of provocative rapper that he believes his community needs to see on a world stage. By performing another unreleased song to close that Grammys set, he was solidifying himself as a rapper whose focus isn’t selling records – at least, that isn’t the top priority – but creating art for those who need it.

Those songs have now been finally been released for sale (and apparently we have Lebron James to thank for that) in the form of untitled unmastered., a body of work which consists of tracks that didn’t make the cut on To Pimp a Butterfly. It’s not for lack of quality, though. untitled unmastered. is, like its predecessor, a fantastic pastiche of traditionally black music (jazz, hip-hop, funk) and keen storytelling, but it has a slightly different tone. Where To Pimp a Butterfly’s thesis is pain, untitled unmastered.’s is revelry. Sure, the songs were recorded some time ago, but it comes across as a well-earned victory lap, with Kendrick polishing his crown and counting up his blue faces.

To Pimp a Butterfly ended with Lamar pulling excerpts from an old interview with Tupac and remodelling it into a conversation between him and his mentor. Tupac wasn’t that great a rapper – like Will Smith, he was actually a much better actor – but he was deceptively smart and complicated figure who said more interesting things in interviews than you’ll find in most of his music. It would have been wonderful to see what he would have done with his life had he not been murdered. Tupac means as much to Lamar’s generation as Lamar will mean to the next. Through To Pimp a Butterfly and the reverberations it sent through American pop culture over the 12 months that followed, Lamar has become a messianic figure, taking his cue from the message his mother leaves him at the end of good kid, m.A.A.d city:

“If I don’t hear from you, by tomorrow, I hope you come back and learn from your mistakes. Come back a man. Tell your story to these black and brown kids in Compton. Let ’em know you was just like them, but you still rose from that dark place of violence, becoming a positive person. But when you do make it, give back, with your words of encouragement, and that’s the best way to give back to your city.”