As the case against the six officers involved in the arrest of Freddie Gray – a 25-year-old black man from Baltimore’s Sandtown neighborhood whose death last April led to a wave of protests and rioting – finally arrives in Maryland’s highest court, local writer Brandon Soderberg traces the legacy of another Sandtown resident, Baltimore club figurehead and queer icon Miss Tony, to consider how Mobtown’s storied tradition of civil unrest is twinned with the combustible spirit of a troubled neighborhood.

At the ninth annual Boundary Block Party in West Baltimore – not far from where, on April 12 last year, Freddie Gray was chased, beat down and arrested by Baltimore Police, thrown into a police van and at some point suffered a severe spinal cord injury before dying in hospital a week later – burgers and hot dogs cost a dollar and face painting stalls share space with activist groups. Two marching bands bound through and get everybody all geeked up.

Nearby, a handful of kids elementary school age are passing a microphone around after stumbling on Baltimore rap collective Llamadon’s Beet Trip freestyle event. Everyone at the party is invited to spit if they feel like it (“even just a bar!”) as a group of besotted beatmakers load up original instrumentals. “Have some fun, but no cursing,” the kids are reminded by MC Action Bastard (you may know him as the author of Beyoncé/Jay Z fan-fic ‘Lemons’). Usually battling isn’t the theme, but these preteens are going in. A boy in black who raps as Lil T zings his friend: “Boy, that shirt look like mine/ You wack boy, you look like Frankenstein.”

A kid sporting a Minion shirt mumbles back: “You don’t wanna say it to my face / Go ahead, try, but you won’t try anymore / Because guess what? You’re just an idiot who doesn’t know how to do math.” The onlookers scream like it’s the best diss they’ve ever heard. A boy in a polo shirt with the best rapping voice I’ve heard in a a while, a bratty, Biggie-like bleat, howls: “Come mess with me and I’ll put you on a diss / Mess with me and I’ll hit you in your—” He looks down sheepishly. You fill in the blank.

“That shit got real, real quick,” jokes Dylijens, a local rapper, producer and organizer. “I went to go get a chicken box and it turned into Grind Time Live.”

Others who grab the mic today opt out of rhyming, and instead adopt the local MCing style, a high-energy rolling commentary heavily influenced by drag and ballroom culture. An older woman in denim chants lines from Blunted Dummies’ Baltimore club classic ‘Where The Hoes At’. Baltimore club, if you’re not familiar, is like all the music at once. It’s binary-breaking party music that sort of “softens” hip-hop and halfway “hardens” house to make something entirely specific to the city, via its savvy for sampling hits and tilting them to the fast-paced taste of Baltimoreans. It’s a culture jammer. You hear Bmore club everywhere. You hear it in those sliced and diced versions of, say, the theme song to Spongebob Squarepants, or the Marvelettes howling ‘Mr. Postman’, which have spread beyond the city’s borders. You hear it indirectly in the warmed-over thump and hump of edgier EDM, and in nearly every white hipster DJ’s setlist since the mid-2000s amid those regional derivations, Jersey and Philly club.

Action Bastard grabs the microphone from the woman to riff on another Bmore club classic — Miss Tony’s ‘Whatzup? Whatzup?’, a hissing, inverted hip-house track from 1994 based around a favorite catch-all Baltimore expression: “How you wanna carry it?”

Action decides to bring the words up to date. With the city less than two weeks away from a mayoral primary election, he plugs in Democratic candidates’ names: “Catherine Pugh said, how you wanna carry it? / Nick Mosby said, how you wanna carry it? / Sheila Dixon said, how you wanna carry it?”

Miss Tony was a queer, Christian Baltimore club icon from the neighborhood of Sandtown-Winchester, the same neighborhood as Freddie Gray. To hear him sneak into the annual block party through one of his iconic tracks, flipped to poke fun at pompous politicians vying for power, is almost too much. Tucked inside of Miss Tony’s short life — he died in 2003 at the age of 36 from complications tied to kidney failure — is the birth of a fast-paced, hyper-influential dance subgenre, some killer songs, and a crooked glimpse into Baltimore’s knotty queer history and storied tradition of political violence.

Tony was a regular on Baltimore’s hip-hop and R&B station 92Q, arriving in drag every day

From the late ‘80s to the mid ‘90s, Miss Tony was an indefatigable presence in Baltimore’s clubs: Hammerjack’s, Odell’s, Club Fantasy, the Paradox, to name a few. He was around six feet tall and over 300 pounds, and he’d vogue, dance, roll around, and hump the floor all while keeping the party moving with shout-outs and joshing routines (“Ooh-wee, that ain’t fair, give that horsey back his hair,” Tony would shout if he spotted a wack weave) in a hoarse, excited voice buttressed by a thick Baltimore accent, stretching “do” into “dew” and “carry” into “curry”.

Miss Tony thrived in the clubs, but you can hear him do his thing on a few infamous early Baltimore club tracks made between 1992 and 1995, which are crying out to be heard by more people: ‘Tony’s Bitch Track’, on which he boasts over gulping house that he has “a PhD in dickology” and reminds men to wash their sweaty balls; ‘Get Ya Guns Out’, where he croons, guffaws, cackles, and impersonates Stephanie Mills over aquatic hard house; and the aforementioned ‘Whatzup? Whatzup?’

Along with those Baltimore-famous tracks, there are about a dozen other Tony songs, and that’s it. One far-ahead-of-its-time Tony obscurity is 1993’s ‘Bitch Track II – Yes!’, an empowerment anthem directed at the US military’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy on homosexuality, with a hook that exclaims, “Yes, I am gay / No, I’m not afraid.” Other songs, especially later ones recorded outside the purview of the club, such as 1996’s perseverance anthem ‘Release Yourself (Tired Of Living Under Pressure)’ and 2001’s ‘Living In The Alley’, a gravel-throated song of self, hint at a sense of gospel-indebted pain that wouldn’t come into club music more explicitly until Rod Lee’s ‘Dance My Pain Away’ (a track that featured on the soundtrack to The Wire).

From 1994 to 1999, Tony was a regular on Baltimore’s hip-hop and R&B station 92Q, where he arrived in drag every day—at least until he stopped wearing drag in 1998 after becoming a born again Christian and changing his name to Big Tony. For those five years, a whole city was hearing and experiencing this outrageous gay kid from the west side on their way to work in the morning. “Just Tony from around the way,” is how more than one person has described him to me—the “just” thrown in there as a tacit acknowledgement of Tony’s sexuality. Some people say Tony introduced voguing to Baltimore, which is certainly not the case, but a lot of Baltimore probably saw voguing for the first time in real life when Tony did it.

The neighborhood has been hammered into a symbol for everything wrong with Baltimore

Not that a neighborhood needs a Miss Tony or a Freddie Gray (or a Cab Calloway or a Billie Holiday, who also both grew up in Sandtown) to “matter”. But Miss Tony, like Freddie Gray, just happened to be from the heavily divested, often vilified Sandtown, and that’s worth repeating, as the neighborhood has been hammered into a symbol for everything wrong with Baltimore, almost always ignoring the people who actually live in the neighborhood.

Sandtown in cold, hard facts (though facts of a certain kind, for sure): less than half of its residents are employed (42%, according to U.S. Census data), one third of its properties are vacant, and it has the highest rate of incarceration anywhere in the state of Maryland. Last fall it was revealed that in Gilmor Homes, the Sandtown housing project where Freddie Gray lived, a number of women were forced to have sex with project housing employees in order to get basic repairs done to their homes. And last month, $4.2 million promised by Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake to provide additional after-school programs in the wake of the Baltimore Uprising was taken back due to alleged “revenue shortfalls”.

And so Sandtown is a neighborhood in which residents could be understandably cynical, though they aren’t, whereas almost everyone in power in Baltimore, who have ignored Sandtown over and over again, most certainly are totally complacent, buck-passing shitlords. At a pathetic and excuse-laden community safety meeting near Sandtown last fall, hosted by Mayor Rawlings-Blake and Baltimore Police commissioner Kevin Davis, residents unloaded their problems. They ranged from hustlers hounding playgrounds, a curious amount of parking tickets being doled out in the area, and demands for some after-school activities for the kids.

For three hours, all of them were met with some variation of “we’re working on it, we can’t do it alone” from a lame duck mayor and a then-interim, soon-to-be-appointed commissioner. One resident told them she hated that their advice to deal with the teens hustling in her neighborhood was “call 911,” because it perpetuates the school to prison pipeline. (For the sake of hearing both sides, Freddie Gray was a heroin dealer – which only really matters if you think that the punishment for slinging heroin in a police-occupied neighborhood, in a deindustrialized, deeply segregated city, is death.)

Sandtown has been ground zero for civil unrest in Baltimore twice over now, after the death of Freddie Gray last April, and in 1968 following the assassination of Martin Luther King. But it’s also the place where Tony Boston – an openly gay, dress-and-wig-rocking vocalist that gave Bmore club music its personality and voice – lived. Some people get why this matters. DeRay Mckesson, the Black Lives Matter activist, who recently ran (unsuccessfully) for Mayor of Baltimore, mentioned Miss Tony in his announcement of his candidacy. “From Ms. Rainey’s second grade class at Rosemont Elementary School to the mixes of K Swift & Miss Tony on 92Q,” he wrote, “to the nights at Afram, Shake N Bake and the Inner Harbor, I was raised in the joy and charm of this city.”

This is the right kind of political pandering: specific cultural memories of a city which one can’t fake and wouldn’t fake, which means it isn’t really political pandering at all. Baltimore filmmaker John Waters has endorsed Mckesson for mayor. Between John Waters and Miss Tony, you’ve got the city’s most influential queer icons invoked by the city’s most of-the-moment black gay activist. There was little to no chance that Mckesson would become Baltimore’s mayor. Catherine Pugh, the chosen Democratic nominee, has already closely aligned herself with the current mayor and current police commissioner. Because Baltimore is so thoroughly moderately liberal, Pugh might as well be named mayor now, some six months ahead of the election on November 8.

I don’t know Catherine Pugh’s opinion of Miss Tony.

Tony and his queerness are mentioned on what is arguably the first Bmore club record, 1991’s ‘I Got the Rhythm’ from Scottie B and DJ Equalizer (two white guys, for what it’s worth – the label of this 12” reads, “He ain’t a white boy, he’s my nigga”). If you flip ‘I Got The Rhythm’ over, you get the B-side, ‘Angel X’, in which a raspy gay vocalist talks a whole bunch of shit about “cum-catching motherfuckers,” boasts of riding a 15” dick, and declares “I live it, I eat it, I suck it, and yes I will fuck it.” And then Angel X calls out Tony, referring to him as “Miss Phony Tony”.

At that point, Tony was a presence in the clubs but hadn’t yet released anything (‘Tony’s Bitch Track’ came out in 1992). This is interesting not because of some probably one-sided beef between two gay voices, but because it means that explicitly gay voices appeared on club wax from the jump.

Dwayne Williams, better known as club legend Diamond K (his hits include ‘Hey U Knuckleheadz’ and ‘Put Ya Leg Up’), who was mentored by Tony and recorded some of his last songs, including ‘Living In The Alley’, ran for city council in Baltimore’s 8th District. He didn’t win. Diamond K’s modest campaign included, of course, a Bmore club song-turned-election jingle. Beyond Tony’s tracks blaring out of club speakers, at block parties, at Baltimore’s annual pride event, and occasionally on club mixes on the radio, it is Diamond K’s 2003 compilation of Miss Tony/Big Tony tracks, Master Of Ceremonies, that has kept Tony’s name out there and introduced his work to each new flock of party kids. The old head club music still goes.

Someone in Baltimore is always paying tribute to ‘Whatzup! Whatzup!’

‘Whatzup! Whatzup!’, the track that Action Bastard hopped on at the Boundary Block Party, is the best known Tony song, though still not all that known outside of Baltimore. Produced by Scottie B and Shawn Caesar in 1994, its slicing, snipping beat gets hit with brief bursts of disco and house, almost like distant memories of a more together, less chaotic kind of dance music, before Bmore club crudely came through. Over its delicious thrum, Tony mentions neighborhoods throughout Baltimore. Imagine cross streets shouted out to a track that sounds like something off electronic duo Matmos’ A Chance To Cut Is a Chance To Cure and you get a sense of the fibrous ‘Whatzup! Whatzup!’ (Matmos, in fact, moved to Baltimore in 2007 and became two more queer heroes of the city).

Someone in Baltimore is pretty much always interpolating or paying tribute to ‘Whatzup! Whatzup!’. The shortlist includes Al Rogers Jr. and Drew Scott’s ‘Conversations’ in 2015, East Baltimore rapper and frequent police target Young Moose’s ‘How Would U Carry It’ in 2014, wily Little Brother-like undergrounder E. Major’s ‘How You Wanna Carry It’ in 2008, and, in performance and in spirit, queer rappers Abdu Ali and DDm.

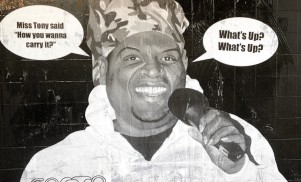

A few years ago, stuck all over parts of Baltimore was a wheatpaste poster by graffiti artist Sorta, depicting Miss Tony gripping the mic with speech bubbles coming out both sides of his mouth: “Miss Tony said ‘How you wanna carry it? What’s up? What’s up?'” They were put up to pay tribute to Tony, and also to put Tony’s subversive career in people’s faces as a wave of gentrification moved through the city.

Over more than two hundred years, Baltimore has more than earned the nickname Mobtown

Because art has predictive powers, back in 2013, two years before the Baltimore Uprising, local composer Ruby Fulton conflated Miss Tony’s Sandtown swagger with Baltimore’s history of rioting in a piece for clarinet, drums, vibraphone, piano, guitar, violin, cello, and voice titled, ‘The Way of the Mob’. Fulton’s piece focuses on the Bank Riot of 1835, when the working class destroyed wealthy Bank of Maryland bankers’ homes because some of the directors had used public funds to make more money for themselves, and it seemed unlikely they’d be prosecuted for it—reasons that sound a lot like the reasons that Occupy, a prequel of sorts to Black Lives Matter, mobilized back in 2011.

‘The Way of the Mob’ fused modern classical composition with the club rhythms of Tony’s ‘Whatzup? Whatzup?’ alongside a soprano shouting out the streets that the Baltimore Bank rioters traversed back in 1835. “Head north on Light Street, towards East Lombard Street, continue onto St. Paul Street…” Although a very slow version of the ‘Whatzup? Whatzup?’ beat moves through the entire composition, it speeds up to a club tempo by the end, a classical interpretation of club’s chaotic rhythms.

“I’ve been wondering if, had any other city been the home of Freddie Gray, in a post-Ferguson climate, things would have gone down the same way,” Fulton said to me about the perceived prescience of her composition. “Or if Baltimore, aka Mobtown’s collective will and personality was a necessary part of everything happening the way it did, and continues to happen. Hard to say.”

Baltimore’s nickname is “Mobtown”. Like “Bodymore” or “Harm City,” it has become a hip, quasi-edgy way to refer to the city–there is the Mobtown Ballroom and Mobtown Studios and the Baltimore City Paper’s news section is titled Mobtown Beat—though Mobtown’s origins are more profound. Over more than two hundred years, Baltimore has more than earned that nickname.

On top of the aforementioned Baltimore Bank Riot of 1835, the city has seen violence on numerous occasions: the first deaths of the Civil War in 1861; three consecutive years of election riots between 1857 and 1859; the Know-Nothing Riot of 1856; two months of rioting in response to the newspaper The Federal Republican’s opposition to the War of 1812; the Gin Riots of 1808; the Doctors’ Riot in 1807, incited by anger over medical practitioners stealing the bodies of the poor for science. More recently there were the 1968 riots and, on April 27 last year, simmering tensions after Freddie Gray’s death combined with a heavy armoured police presence and a decision to shut down public transport just as high schools were letting students out resulted in rioting. Baltimore is a city that fucks shit up when it needs to—or, to be fair, feels like it needs to fuck shit up.

People in power have cleverly, callously absorbed the rhetoric of the second civil rights movement

Is it even possible to get over one thousand people in one city to take to the streets over a police murder more than a few times? It seems unlikely. Protesting as an extracurricular activity hits a wall quickly. Protests in Baltimore since last April have been consistent, though more sparsely attended. The onus of change is back on the grassroots activists. It will not come from imminent next mayor Catherine Pugh, or even from a failed mayoral candidate and activist like DeRay Mckesson. It will come from indefatigable “frontliners”, such as PFK Boom.

“I don’t march no more,” he half-seriously told me at the Boundary Block Party. He, along with a few others, is working on a community policing project called 300 Gangstas. Supposing it all works out, there won’t be a need for the cops anymore. If anybody in Baltimore can make this work, it is PFK. He was a soldier last April, keeping people in check, tightening up the line, and in making marching Baltimoreans feel cared for and even more fearless. Protests need PFK more than he needs them.

There’s so much pain and fear swimming around Baltimore–more than usual. Freddie Gray’s family was awarded $6.5 million in a civil suit last September. Not long after, Gray’s mother attempted suicide. The police are afraid of rioting, unwilling to acknowledge their role in stoking the fear which triggers unrest. Residents have bought into the police narrative that rioting is imminent. Last December, after the trial for Officer William Porter (the first of the six officers charged with Freddie Gray’s death) was declared a mistrial and protesters took to the streets, I watched a Maryland Deputy choke-slam a 16-year-old for loudly chanting into a bullhorn. For a moment, it seemed like the powers that be would get the violence they anticipated. Protesters bolted away from the teen and the pile of deputies on top of him, and headed up the street to city hall to keep the protest going.

Over in East Baltimore on April 27 this year, the one-year anniversary of the day the Baltimore Uprising got violent, a plainclothes officer shot a 14-year-old boy in the leg and shoulder. The boy, five-feet-tall Dedric Colvin, was holding a basketball in one hand and a BB gun pistol in the other, and ran when the police told him to stop. They thought the BB gun was a real gun. Colvin’s mother ran out onto the scene only to be put in handcuffs and taken to police headquarters.

At a press conference after the shooting, Police Commissioner Kevin Davis asked why a 14-year-old boy would go outside with a “replica” gun and effectively blamed his mother for letting him leave the house with it. A few days later, at a National Association of Black Journalists conference, Davis softened his rhetoric and admitted that had this child been white, it’s doubtful he would have been shot by police.

Davis’ comments are a case study in the ways in which the people in power have cleverly, callously absorbed the rhetoric of the second civil rights movement and pepper their pronouncements with it (“school-to-prison pipeline”; “we can’t incarcerate our way out of this”) even though policies have, for the most part, stayed the same. It’s all rather Orwellian.

Meanwhile, justice (okay, “justice”) has been deferred. More than a year after Gray’s death, the trials of the six officers charged (Caesar Goodson Jr., William Porter, Brian Rice, Edward Nero, Garrett Miller and Alicia White) started again last week with the trial of Officer Edward Nero, who is charged with second-degree assault, reckless endangerment and two counts of misconduct in office.

The restarted trials come after Officer Porter’s trial ended in a hung jury in December, and the city wandered through months of arguments about whether officers could be compelled to testify against each other—back-and-forth court junk that no regular person can possibly understand. This is the slow, portentous grind of “justice” they tell us all about. It doesn’t feel like justice at all.

A combustible, indefatigable example of Sandtown joy shone through

Across town in West Baltimore in front of the rebuilt CVS Pharmacy, activists, residents, musicians and poets recently gathered to commemorate one year since the uprising when news came of the shooting of Dedric Colvin. The cops had been bugging people all day over, a few people muttered. A helicopter, a drone, and a sizable and visibly nervous police presence hovered around the activists’ gathering. Five cops had approached activist, artist and cook Duane “Shorty” Davis and asked him to shut down Shorty’s Boot Legg BBQ (slogan: “So good it’s illegal”), a non-permitted grill on the sidewalk giving away free hot dogs.

Half-facts flew through the frustrated, scared crowd: a teen had been shot. He was very young. Nine or ten. Then for a second it was a she. She was 14. No, she was 13, maybe. Wait, it was a he. Damn. The police had gone and killed a girl, no, a boy. He got shot in the leg. He isn’t dead. Still, what the fuck? On this day of all days, y’all. A march sparked up. Fronted by PFK Boom—on this day at least, he compromised his “no marching” declaration—it moved through Gray’s neighborhood.

“Everybody, I told y’all about skin in the game?” PFK faced the group as they approached the spot where Freddie Gray was arrested. “This where the fuck your skin goes in the game.”

As the march looped back around to the CVS where they would gather for West Wednesday—a weekly event for Tyrone West, who died in police custody in 2013—a teal-suited marching band eased tensions, at one point singing along to Aly-Us’s ‘Follow Me’, a spirituality-in-the-club classic from 1992 which surely shared space on setlists with Miss Tony songs.

The Baltimore Entertainers Marching Band were there to celebrate a new clothing store opening up. Whether it was a good thing they happened to appear at a fractious moment is debatable, but that is what happened. It was another moment where, with Gray’s death still informing nearly everything that was happening on the ground, a combustible, indefatigable example of Sandtown joy shone through.

Maybe one day there will be a Miss Tony statue in Sandtown

During the Baltimore Uprising, in the week or so of protest before the April 27 rioting, when a sea of frustrated, fervid people marched, they passed right by a statue of Billie Holiday at Pennsylvania Avenue and Lafayette Avenue. Many people stopped and rested next to it. This statue, however, doesn’t give you much of breather from anything. Designed by James Earl Reid and erected in 1985, it functions as both the prototypical Lady Day memorial—hands out, mouth curled, flower in her hair, singing—and something far more loaded. Relief sculptures at the bottom of the statue show a baby hanging upside down with its umbilical cord attached, a crow tearing apart a flower, and a black man, naked and lynched. The reliefs were added in 2009, originally censored from the design when it was erected in 1985.

Maybe one day there will be a Miss Tony statue in Sandtown. This is not as nutty as it might seem. There is currently a half-successful campaign to put a statue of Divine, the grossly fabulous, shit-eating star of John Waters’ sickest movies, in Baltimore’s Mount Vernon, a once fulgent “gayborhood” turned bougie midtown area. The Divine statue would be close to Leon’s Leather Lounge and not far from where the legendary gay bar Club Hippo once stood—it closed last year and will soon be home to, yes, a CVS Pharmacy. So, a Miss Tony statue would be nice. Nice. But that’s about all it would be.

Miss Tony was from the West Baltimore neighborhood of Sandtown-Winchester and Freddie Gray was from there too.

Brandon Soderberg is on Twitter