A Tribe Called Quest are widely hailed as one of the greatest rap acts of all time. Their catalogue isn’t without its blemishes however. 20 years ago, they released Beats, Rhymes and Life and disappointed fans who couldn’t come to terms with its new flavor and darker tone. But as Jesse Bernard argues, its blend of realness, reinvention and subtle afrofuturism make it a misunderstood classic.

“You on point, Tip?”

“All the time, Phife.”

In 1996 New York, this was a familiar couplet and its creators a chart-topping phenomenon. Queens rap trio A Tribe Called Quest had three impeccable records under their belts before their fourth crash-landed that summer. People’s Instinctive Travels… was a game changer, the album that cemented an experimental sound that would dominate ’90s hip-hop. Its follow-up, 1991’s acclaimed The Low End Theory was even more ambitious, with critics and fans praising its innovative fusion of jazz and rap. Midnight Marauders then sealed their status in 1993 – while it didn’t achieve the breathless praise of its predecessor, it took them to the top of the Billboard charts.

Then came Beats, Rhymes and Life, their first real disappointment. Three years of ceaseless touring had cracked the sunny demeanour of their previous outings, replacing it with an unfamiliar darkness. Roots drummer Questlove summed up the feeling in a 1998 article for The Source: “By this time most attitudes were, ‘if Tribe ain’t moving the world with each release, then we won’t stand for nothing less.’” On point all the time? Guess not, shrugged many fans and critics.

Twenty years on, the album’s dismissal feels unfair. Each Tribe album to this point had been innovative in its own right, setting new standards for sampling, production and lyricism. Phife Dawg, Q-Tip and Ali Shaheed Muhammad had blown out of St Albans anonymity with a fresh alchemy of jazzy samples, observant, socially aware rhymes and vivid Afrocentric themes. Beats, Rhymes and Life saw a sudden leap from that winning blueprint. Phife Dawg, who died earlier this year, found himself in an awkward position, often having to trade rhymes with Q-Tip’s cousin Consequence instead of Tip himself. A capable if not breathtaking rapper, Consequence appeared throughout the record, even replacing Phife on the album version of stand-out single ‘Stressed Out’. Elsewhere, Tribe broke character to bemoan the state of contemporary rap (‘Phony Rappers’), a track that played to their base but revealed a fraying connection to the youth.

Where some may have predicted or anticipated more good-times vibes along the lines of Midnight Marauders, instead came the product of an altogether different group, in an evolved hip-hop landscape. Following that album’s commercial success, Q-Tip (now Kamaal the Abstract) and Ali Shaheed Muhammad converted to Islam, leaving Phife Dawg feeling increasingly excluded as he relocated from New York to Atlanta. When Tip and Muhammad formed production group The Ummah with a Detroit up-and-comer who’d later go by the name J Dilla, Phife had a good reason to assume that the group was done. “I started feelin’ like I didn’t fit in any more,” he told Linda Burton in 2006. “The chemistry was dead, shot,” he confirmed later on in Michael Rapaport’s 2011 documentary Beats, Rhymes & Life: The Travels of a Tribe Called Quest.

The truth is, the band were tired and cracks were undoubtedly showing on Tribe’s fourth full-length. A little of their magic had been lost, but there’s still plenty to love and admire. Here’s five reasons why although Beats, Rhymes and Life wasn’t their magnum opus, it remains an important part of their catalogue, and one that still contains some of their most urgent tracks. Even at one of their lowest creative and collective ebbs, Tribe were gripping without fail.

It introduced the world to The Ummah – and J Dilla

One of the album’s greatest legacies is The Ummah, the production trio it welcomed to the world. Q-Tip and Ali Shaheed Muhammad were known for their love of jazz and rock samples, but The Ummah brought soul into the mix. This was thanks to the inclusion of young Detroit producer James Dewitt Yancey, then known as Jay Dee and later known as J Dilla. Dilla’s Detroit roots, and the Motown connection that goes with that, spilled out into the group’s sound, informing a growing movement of artists with an appreciation for progressive, snare-heavy, soulful R&B – a movement known as neo-soul.

The trio would go on to lay distinctive beats for Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston, Busta Rhymes and others. More importantly however, The Ummah shows the ascent of a hip-hop icon in Dilla. The producer had found success in a sound he’d cemented on The Pharcyde’s Labcabincalifornia a year earlier in 1995, and his production on Beats, Rhymes and Life sits at the very center of the album. It’s no wonder that he’s often handed the blame for the album’s chilly mood – in fact his soulful blend of samples and clipped beats (which he would explore in finer detail on Slum Village’s debut Fan-Tas-Tic Vol. 1) has aged like a fine wine, foreshadowing his later greatness.

Q-Tip was still positioned in the driver’s seat and Ali Shaheed Muhammad was still around, no doubt, but Dilla’s fingerprints are all over ‘1nce Again’, ‘Keep It Moving’ and ‘Stressed Out’, giving the tracks a soulful snap that reframed Tribe’s sound almost too quickly. It’s easier to enjoy the tracks now with the benefit of hearing The Ummah’s evolution on Tribe’s “final” album, The Love Movement, but the indicators were there on Beats, Rhymes and Life – a legend was born.

It’s a snapshot of hip-hop at its mid-‘90s so-called peak

By the mid-‘90s, hip-hop had grown in size, depth and personality. Crews, labels and stars had formed beyond New York, as Outkast so notably made clear at The Source Awards in 1995, when they won Best New Rap Group to a chorus of boos from an audience sold on coastal dominance.

The Source Awards was also the battleground for an East Coast-West Coast rivalry that would threaten to tear apart the scene completely. Death Row boss Suge Knight took a direct shot at his East Coast rival, Bad Boy’s Sean Combs, saying, “Any artist out there that wanna be an artist, stay a star, and won’t have to worry about the executive producer trying to be all in the videos, all on the records, dancing—come to Death Row!”

This was interpreted as a rallying cry and Puff responded in his performance later that night, exclaiming, “I live in the East, and I’m gonna die in the East,” to New York audience peppered with LA Bloods and Crips. Even Snoop Dogg joined the scrap, asking, “The East Coast ain’t got love for Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg?”

The tense atmosphere in the rap community provided the perfect backdrop for Beats, Rhymes and Life. Q-Tip had been unwittingly pulled into the beef at 1994’s Source Awards, when 2Pac began performing, probably accidentally, while Q-Tip was still on stage.

Later on, Tip would be taken to task by Ice Cube’s Westside Connection in ‘Cross ’Em out and Put a K’. WC had heard that Tip was tired of gangster rap (“I once knew this bitch by the name of Q-Tip / Who claim he had a problem with this gangsta shit”), and detailed the East Coast rapper’s gruesome demise in response. Not wanting to escalate the beef any further, Tip sets the record straight on ‘Keep It Moving’, assuring he “ain’t no West Coast disser”.

As chronicles of the so-called golden age go, it’s an insightful one. Here, Tribe represented something far bigger than an intramural beef, they showed how much more could be achieved by black individuals pulling together – black empowerment through unity.

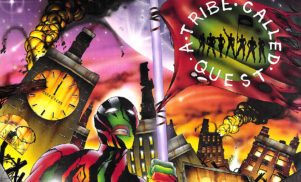

Its artwork pushed their afrofuturism to a powerful, political extremes

Aesthetically, Beats, Rhymes and Life was the last A Tribe Called Quest album to follow the Native Tongues theme of afrofuturism. Its colourfully illustrated cover sees a striped woman carrying a flag in what appears to be a post-apocalyptic metropolis, painted in rich red, green and yellow pan-African colours. One interpretation of this is of a land where revolution for African Americans has finally been realised.

Although Tribe saw themselves as hip-hop’s progressive social commentators, they were also considered as the stubborn antithesis to the commercial side of the genre. Previous album covers portrayed their avatar as peaceful and static. On Midnight Marauders, the woman was portrayed in a rhythmic stance. On Low End Theory’s sleeve, inspired by the Ohio Players’ classic album covers, she’s crouched naked, covered with black stockings. Beats, Rhymes and Life saw her at her most dynamic and angry, in a pose that – a few years after the beating of Rodney King, with tensions still raw – felt defiant and political.

It flew in the face of so-called “real hip-hop” at the time

Three years had passed since Midnight Marauders and the landscape of hip-hop had changed. The genre, thanks to dominant albums by Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Snoop Dogg and 2Pac, had certainly become more visible in a mainstream sense. Whilst there was still a viable model in socially conscious rap, a new crowd of artists had arisen who represented a more ostentatious, commercially-driven style and had begun to take over MTV.

Puff Daddy and Biggie had owned the rap, R&B and pop charts with their hook-laden crossover-friendly street anthems. Jay Z would soon prove beyond Reasonable Doubt that he was a force to be reckoned with. On the other side of the US, 2Pac, Snoop and Ice Cube led the West Coast charge, each staking their own claim to hip-hop glory. In the South, the sound was diversifying even further with Oukast in Atlanta, Master P in New Orleans and Three 6 Mafia dominating Memphis. Inevitably, as the culture began to shift, so did the sound.

Not that Tribe really cared. Instead, they stayed in their own lane, doing what they did best. ‘Phony Rappers’ poked fun at less capable rappers who had rapidly risen to stardom without cutting their teeth in the manner that used to be expected. Whilst they took no particular aim at any individual rappers – to have done so would have had interesting results – it felt defiant in its refusal to embrace a sound and energy that was impossible to ignore.

Some of the songs are Tribe GOAT contenders

‘The Hop’ remains one of A Tribe Called Quest’s masterclasses in sampling – a traditional boom-bap rap jewel blessed with Tribe’s signature New York storytelling. The repetitive keys from Henry Franklin’s ‘Soft Spirit’ twinned with The Ummah’s soulful production and the well-worn tag team of Q-Tip and Phife gives the track a spring in its step that elevates it to classic status.

Although Tribe hadn’t quite mastered the R&B-rap sound quite like Bad Boy and co, ‘1nce Again’ is a formidable attempt at crossing over without selling out. The first single to be released from the album, the song had to set a precedent and mark the return of hip-hop’s three kings. By that time, a measure of success in hip-hop was Grammy awards and ‘1nce Again’ won the group a Grammy award for the best rap performance by a duo or group in 1997. They didn’t achieve this alone – such a feat would require the guest appearance of Tammy Lucas, who had previously featured on one of The Neptunes’ earliest productions, ‘Tonight’s The Night’ by Blackstreet.

Giving a nod to old fans, Tribe returned to a sound more akin to their debut album on ‘Word Play’. What makes this attempt so successful is the deliriously minimal, soulful production. The pared-down beat was uncharacteristic of Tribe, but is undoubtedly one of the album’s highlights, one of their career highlights, and further proof that Beats, Rhymes and Life just isn’t worth the hate.