Available on: Border Community LP

It usually seems unsporting when an artist derides their fanbase. But in the case of James Holden – who has come pretty close once or twice – you can’t really blame him. By way of explanation, I present to you his Discogs page: a dumping ground for “friendly advice” from die-hard fans urging him to return to the melodic, trance-indebted style with which he made his name a decade ago, and lamenting the perceived decline of Holden and his label Border Community as they have strayed into progressively “weirder” terrain. These are the people, one imagines, who still go to Holden’s gigs expecting to hear variations on his landmark 2004 remix of Nathan Fake’s ‘The Sky Was Pink’ ad nauseam, and leave feeling not only cheated, but self-righteous in their anger.

The Inheritors, Holden’s first album in seven years, might reasonably be read as a sustained and heartfelt “fuck you” to those people. From the ramshackle frenzy of opener ‘Rannoch Dawn’, all muffled drum tattoos and meandering open-fifth drones, it’s clear that we’re not going to get a re-run of ‘A Break In The Clouds’, or even an extension of Holden’s vaunted 2006 LP The Idiots Are Winning. It’s clear, in fact, that Holden is on another page entirely.

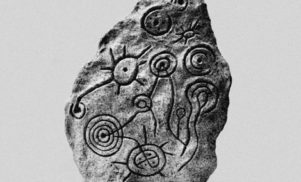

This record is inspired by a 1955 William Golding novel set at the time when homo sapiens began to take over from their neanderthal predecessors. Similarly, Holden explores the idea of musical evolution, sketching out an alternate history where what he calls the “sprawling inventive madness of the ’60s and ’70s” wasn’t killed off at the hands of the digital revolution. The Inheritors, he says, is an attempt to foster a “utopia for the non-competitive idea”; these tracks were recorded “like folk music”, in a series of live takes using a complex modular synth setup, and draw on “ceilidh music, pentatonic folk scales, and ancient pagan rituals” for their inspiration.

This sort of neo-bucolic worldview tends to be odious and hypocritical in a maker of electronic music. It is almost invariably followed by some kneejerk comments about “authenticity”, or a salvo of cliched arguments about “soul” and “humanity” being absent from electronic sound. Equally worrying is the scale of the thing: in its press release Holden aligns this fifteen track, 70-odd minute epic with the grand album projects of old, expressing a desire for it to be “a whole new world, a mythology, complete… As opposed to a product in a cycle”. At this point your hubris klaxon ought to be wailing dolorously. Here, you might reasonably assume, is a descent into self-indulgence writ large; the protracted sound of a viciously swollen ego committing gory seppuku.

It’s remarkable how inaccurate this assessment would be. As tempting as it is to pooh-pooh Holden’s overblown ambitions, in The Inheritors he really has created an album of striking originality, and one whose more excessive aspects feel largely justified. Of course, there are fleeting points of continuity with his past work. The title track and ‘Renata’ both trade in distinctively Holden-esque melodies, albeit rendered in soupy, indistinct tones. The excellent ‘Blackpool Late Eighties’ meanwhile, with its mirage-weak techno pulse, is the closest we’re going to get to ‘The Sky Was Pink’. But where in Holden’s past work these meandering tunes might have been subjected to a succession of ferociously precise edits and modulations, here they are marshalled in a far more haphazard manner, as the producer attempts to steer the “chaotic systems” created using his modular setup and visual programming language Max/MSP.

The album’s highlights come when Holden allows these systems to lead him into less familiar terrain. In their wanton, chaotic density, these sound like pretty much nothing else around – their closest relative is probably the kosmische pioneers of old. ‘Sky Burial’, with its smoky organ tones, could be some unearthed ancient dirge; ‘Gone Feral’’s tart melodic squiggles are periodically consumed by thumping, atavistic percussion. ‘The Illuminations’ is a little more distilled but equally rich, its delicate arpeggios hinting at a fragile pastoral optimism. Each of these moments suggests that Holden has succeeded in his mission to “make something uncompose-able, unwritedown-able”: they are fiendishly complex not in the manner of a Wagnerian opera – a triumph of intellect over material – but in the same way that the quasi-fractal patterns found in nature can be so pleasing to the eye, their surface order only half-intentional, but all the more beautiful for it.

Granted, occasionally Holden’s complex alchemical processes don’t yield entirely pleasing results. ‘The Caterpillar’s Intervention’, led by the brash sax-work of Zombie Zombie’s Etienne Jaumet, takes the overload ethos a bit too far; ‘Delabole’, in its gothic angst, isn’t all that convincing. And funereal closer ‘Self-Playing Schmaltz’ is a far too maudlin to conclude an album so teeming with unusual life. But even in these weaker moments Holden is consistent in outlining his bold, strange aesthetic world – a world that is not only acres apart from his past work, but from that of the majority of his peers, too. It’s an impressive achievement – and, what’s more, one that’s likely to piss off his fans a treat.