Few can intoxicate and beguile quite like Laraaji.

Edward Larry Gordon’s calling wasn’t always music – he spent his late teens plying his wares as a stand-up comic and occasional actor (including a small role in black cinema classic Putney Swope). Having picked up an autoharp in a pawn shop, Gordon began experimenting with unusual opening tunings and audio processing equipment in the 1970s, performing at New Age meets and on the streets of New York. In one of Ambient music’s taller tales, Gordon – now rechristened Laraaji – was spotted in Washington Square Park by a post-Roxy Music Brian Eno, who left a message in his busking case asking if the pair could record together. What followed was 1980’s Ambient 3: Day Of Radiance – a coruscating wash of zither and autoharp tones, and one of the most ecstatic ambient releases of the decade.

The album opened the door to a profusion of cassette releases, international performances and collaborations. Almost all feature his twinkling zither playing, and almost all unfurl with grace and patience, but, within those parameters, his releases pull in different directions – from weirdo trip-hop to spectral noise rock, from music made in caves to tapes laid down in bedrooms. Nowadays, Laraaji splits his time between making music and running instructive “laughter workshops” (you can watch Yuck/Hebronix sourpuss Daniel Blumberg being subjected to one here), but he’s still very much a creative force – and, Christ alive, he looks good for 70.

As part of their current reissue drive, Brian Eno’s All Saints label have reissued a clutch of vintage Laraaji albums: 1987’s Essence/Universe, 1992’s Flow Goes The Universe and 1995’s The Way Out Is The Way In (bundled as Two Sides To Laraaji), and a new odds’n’sods compilation, Celestial Music 1978-2011.

With fresh light being shed on his back catalogue, and with the uninitiated in mind, we asked Laraaji to introduce a series of key records from across his canon. From his earliest releases to his weirdest collaborations, these are the records to start with, as assessed by the man himself.

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 1/7)

01. EDWARD LARRY GORDON

Celestial Vibration

(SWN, 1978)

Celestial Vibration was my first vinyl recording, and it was assisted by a friend named Stuart White, who helped produce it for me. It was zither, mostly electric freestyle zither, with open tuning and with some kalimba, which is African thumb piano, and lots of treatment. I used both a rhythmic hammered zither on the album, as well as open-hand washes and strumming. It was recorded in 1978 or 19779, I believe, in New York, and was my first major recording. It didn’t get an international distribution: it was more local, and released through a distribution company called Relaxation Music here in the United States. It’s kind of exploratory, in that it doesn’t stay calm all the way through, and i go through sounds – using the instrument to produce a variety of sound. I go through my vocabulary on the electric zither at that time, I pretty much go through it and expose it on that album.

Had you made many recordings prior to that release?

I’d done a handful of tape cassette recordings prior to that release, and they were being distributed by me directly to audiences and people who were taking yoga classes at that time, having them played at yoga classes.

Is it an album you ever return to? You must have refined your technique so much in those intervening decades.

Oh yes, I tend to stay in a particular zone much longer on more of my later albums. I’ve listened to it quite a bit lately because it’s been re-released about two years ago by Soul Jazz Records out of the UK as well, and it was faithfully reproduced and re-released, It’s got a strong mood – an introspective mood, and a very jazzy mood, and a very dance-y mood, like folk dance. And also some sweet tone poem passes during the performance.

02. LARAAJI

Ambient 3: Day Of Radiance

(Editions EG, 1980)

The Day Of Radiance album was produced by Brian Eno, and at that time he had come across my performance one evening while I was busking in Washington Square Park in the Village in New York City. He left a message in my busking case, inviting me to talk to him about participating in his Ambient series project. So I contacted him the following day with the telephone number he had given me, and we met soon and discussed positively working together and recording the five full tracks of Day Of Radiance there in New York City.

The recording process involved, for the first time, high-quality microphones and less electronics on my part. He added treatments later on after I’d finished recording the tracks. That was the first time that a producer gave me a sense of where he wanted me to go with the recording process, as opposed to my just going freestyle all the way.

How did he go about directing your performance?

He tried to softly lecture me on the concept or the idea of ambient music – music to provide a space or an environment in which the listener could go about doing whatever they were doing. Music that wasn’t so imposing or intervening, but was present as space in which the listener could just immerse themselves, whilst thinking or going about some other project.

I’ve always found Day Of Radiance‘s presence in the Ambient series interesting, because it’s such a bright, and crisp, and riveting album. It commands attention, I think, rather than drifting into the background.

I might have failed! [laughs]

A pretty gilded failure in that case! I presume it must be an album people ask you about a lot.

Yes, as a matter of fact, I meet people who were teenagers when that had come out. They tell me how they used to play it in rooms with the lights out and get stoned! Schoolteachers tell me they use it to calm down their students, and others tell me they just have a wonderful introspective experience with the recording.

As someone that takes therapy workshops yourself, the many different therapeutic purposes to which the record is put must be of interest to you.

Yes, indeed. People going through hard times, hard periods of their life, find it very calming and soothing. It makes me feel very good. It’s an extension of my intention to be present in my music in a way that supports people, helps lift their spirits, provides them with a day of radiance in their listening experience.

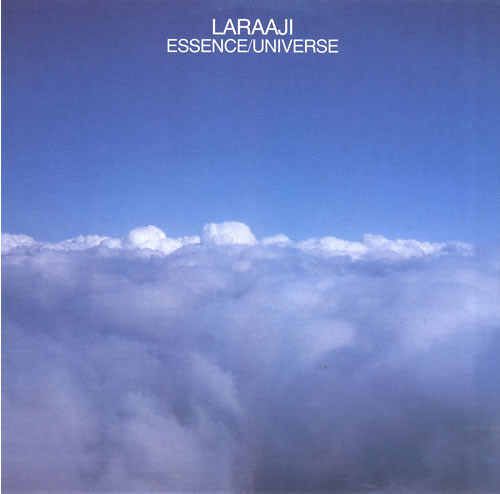

03. LARAAJI

Essence/Universe

(Audion, 1987)

Essence/Universe was produced in Washington DC with Richard Ashman who owned a studio there and extended his studio to me for next to nothing to do this recording, He was the one that encouraged me to try putting lots of treatment on the zither – enough reverb so that it became like a smooth bed, a pad of zither unfolding, with soft celesrtial voice tones and soft chimes to create this rather ethereal, floating sonic pad. It consisted of two 30 minute passes, because it was deliberately done for an album. And that one was released first through Audion Records, which very quickly went under, so the album stood hanging in the middle of the sky with no distributor. It was published by Opal at the time, and that eventually was released in vinyl and CD and cassette.

It’s not necessarily as clear that you’re listening to a zither or an autoharp as it is on your earlier releases. It reminds me of what a lot of guitar bands were trying to do around the same time – produce this heavenly sound that was divorced from the instrument from whence it originally came.

Yes, and that’s one issue that comes up a lot when people finally see me play live in performance. They’re relieved to see what the instrument is, because, as they report to me, when they first heard the music, either on the radio or playing somewhere, they couldn’t make out what the nature of the instrument was that was making this sound, because of the way I usually treated the instrument.

Watching someone play an instrument, and seeing how it’s being made on the fly, is a very different experience to begin presented with sound blind, and having to work out what you’re hearing. Do you prefer being in front of an audience, and showing them how you’re creating this music from your instrument, or do you like being able to potentially bamboozle your listeners?

Both of them are fun. I must admit that I attempt to create the illusion of an orchestra, or of many different instruments going on at the same time, and it’s easier to keep that illusion going if people aren’t watching me play. And on the other hand, since I was given the gift of music lessons at a very early age, and enthusiasm for playing a musical instrument, I like the idea of potentially inspiring other young audiences to watch me and themselves get the inspiration to go out and try playing a music instrument. So I like being visually available, hopefully exposing other musicians or young ones to experiement and explore playing a musical instrument.

04. LARAAJI

Flow Goes The Universe

(All Saints, 1992)

Flow Goes The Universe was a collection of live performances and studio performances. At that time, I was touring with Opal Evening – it was composed of several artists who were releasing albums through Opal Ltd, which was Brian Eno’s publishing company in the UK. On that album, I used a Korg M1 synthesiser; I used electric zithers, usually two electric zithers in performance; I used African thumb piano called mbira; and I used voice as a sound instrument. And I used Mother Nature – the sound of water dripping in a cave. I got closest to actual tone poem compositions with Flow Goes The Universe.

‘A Cave in England’ was raked kalimba while moving around inside of a rock quarry cave in North England, and that was the first piece of music that I recorded on what was fresh technology at that time, and that was the Sony DAT Walkman. ‘Being Here’ is a very long, immersive piece that was recorded in New York City on multitrack. ‘Mbira Dance’, ‘Zither Dance and ‘Kalimba Dance’ were recorded either in Zaragoza or in Northern England. ‘Immersion’ was recorded on a Korg M1 keyboard, and ‘In Continuum’ was bowed zither, using a cello bow on the bass string of the zither autoharp, whilst using flanger and delay effects.

There was one piece that was on the album initially, but that was withdrawn because they felt it was out of character with the major flow of the album. It was called ‘Laughter In Tongues’, and it was a very laughter-oriented, up-energy composition. The album initially was released with 12 or 13 tracks, two or three of which which were nothing but two, three, four seconds of silences. Michael Brooks, the producer at the time, felt that the Japanese market would participate interactively by programming the playback of the album, in shuffle order. You would have occasional silences between the pieces. But, as we learned, the rest of the international scene didn’t quite figure out how to use it creatively, and so it turned out to be more of a confusing element, not included in later releases.

05. AUDIO ACTIVE & LARAAJI

The Way Out Is The Way In

(Gyroscope, 1995)

Audio Active were a threesome from Japan, and they worked with a lot of heavy technology that was new to my ears and understudying at the time. Ray Hearn, the producer of that album and the promoter of that performance group, approached me to send him a DAT tape of my rap at the time, my rap and poetry. He took that DAT tape and gave it to Audio Active, and they cooked up The Way Out Is The Way In, dubbing my voice in over their electronica exploration. And I was impressed. We bounced it back by mail – at that time, I didn’t work with downloading music onto the internet. We came up with that album without my having met the group in person, until eventually after it was released we did one or two performances together, one in Japan and one in New York.

Particularly given your background in comedy performance, was it liberating to be able to do those sort of performance? Where your words were front and centre rather than your playing?

Yes, it was – although when I performed live I did use zither. but to get into rap, that was new for me, to do it live.

You’ve talked in the past about the importance of play, very directly with laughter, and it’s an incredibly playful record. It’s very childlike in the extremity of the play.

[very rich laughter] Yes, and to my surprise, when I performed it in Japan, I was given an extra 20 minutes to conduct a guided laughter workshop with the audience. And after setting it up, verbally introducing how it was going to go, I then proceeded to laugh for 20 minutes, inviting the audience to come along with me, and it didn’t appear that anyone in the audience in Japan laughed! [laughs] But afterwards, backstage, this one Japanese gentlemen came back, bowed and smiled, and with lots of exuberance, thanked me for doing it and that he had a wonderful time. So obviously the Japanese laugh very quietly!

06. BLUES CONTROL & LARAAJI

FRKWYS Vol. 8: That Healing Feeling

(RVNG Intl, 2011)

It started with Lea Cho and Russell Waterhouse, who compose Blues Control. They stumbled across a performance of mine in Greenwich Village some years ago, maybe six years or so, and they asked me for my card – and I forget them. They approached me over the years by phone to see if I was available to perform with them at various performances in New York, but it conflicted with my schedule. Eventually, they approached me to do a recording with them – RVNG Records had proposed the idea of them recording with artists further down the line of experience in that direction of music. They chose me, and we met at Black Dirt Studio in upstate New York without my having remembered who they were, but I trust the process, since I’ve been in jam sessions so much in my life – just jumping in cold and making sense out of a collaboration of any variety of instruments was very natural to me.

So they showed up, and I showed up with my musician-partner, friend-partner at that time, Arji Cakouros. So there’s the four of us – Russ Waterhouse, Lea Cho, Arji Cakouros and myself in the studio, just exploring music that was based around the tuning of the zither. Russ Waterhouse on his multiple instruments, electronica, and Lea Cho on her keyboard, and Arji on her percussion, and me on the zither, voice, kalimba, and some beats. We hung out in the studio for 4 or 5 hours, and just let it happen. I got into using the snare drum for the first time, using a lot of voice, suggesting beats, and initiating directions with the zither and allowing Blues Control to initiate directions at other times. They spent most of the time mixing without my being present, and they came up with the final mix that became That Healing Feeling

Earlier this year, I interviewed another musician often categorised as an Ambient artist, Robert Rich. He was saying people that listen to heavy metal come up to him and say, “Even though I normally listen to very noisy and aggressive music, I still listen to yours, because even though it’s quiet, it has the same degree of intensity that I get from louder music.” Do you listen to noise music? Is there some crossover between the music Blues Control make and the music you make?

I don’t listen to that kind of music, except by accident, and Blues Control were the closest I came to being introduced to the idea of Noise music as a deliberate form. I did include some of that noise factor in the Celestial Vibration, exploring the zither and its vocabulary, and when I go with dance companies, sometimes I’m invited to explore rather noisy and cacophonous kinds of sounds. But Blues Control was the fist time I came to a legitimate art form that was built around noise, or accepting noise as a content of performance.

I suppose laughter is a very noisy pursuit.

Yes! Thanks for opening me up to that idea – laughter is rather cacophonous, and non-tonal.