The first rule of post-rock is that you definitely don’t call it post-rock.

Slipping into use in 1994 after Simon Reynolds coined it in Mojo, the term was almost as universally reviled as “IDM”, polarizing bands, fans and critics alike, who saw it as disparaging. Looking back, it seems more fitting now than it ever did then, heralding a shift in both mindset and technique as bands increasingly headed to the studio for inspiration as the digital age took hold.

As its prefix makes clear, post-rock contains a sense of an ending, a feeling that rock as we know it is over. We can’t go back, even if we wanted to, and pretending otherwise would be insincere. Post-rock is certainly sincere, often to the point of being embarrassingly earnest; post-rock wears its heart on its sleeve, but then scribbles over the evidence and mumbles an excuse not to tell you what it’s really thinking.

It’s no coincidence that the genre and the term emerged just as four decades of relative stability were overturned by the abrupt collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the cold war. Just as some scholars were declaring “the end of history”, a seam of would-be rock musicians sensed that it was time to step back from the crash site of American post-war culture and survey the damage. Like the term postmodern, post-rock doesn’t just mean after rock – it’s also against rock, a rejection of an outmoded narrative. Post-rock embraced uncertainty and indecision, and shied away from rallying statements, wary that any aesthetic rebellion can easily be co-opted and commercialised.

The performative emotion of the live performance, for so long the beating heart of rock, was rejected in favour of studio experimentation. Flamboyant frontmen were replaced with mumbled made-up languages, or simply removed altogether. Guitars became texture factories instead of riff machines, and electronics were adopted for the same task. The band members themselves became anonymous, practically invisible (would you really recognise a member of Tortoise if they passed you on the street?) and the studio nerds, previously relegated to the job of “producer” or “engineer”, became de facto frontmen, pushing and pulling their groups’ sounds into glorious new places.

Whether you accept the term or not, this thing called post-rock encompasses some of the most exciting albums of the last 25 years. From stone-cold classics to unsung obscurities, here are the 30 you need to hear. CR

Listen to a YouTube playlist featuring a track from every album here.

30. Mono

Under The Pipal Tree

(Tzadik, 2001)

Mono’s debut is something of a surprise. Released almost a decade into post-rock’s existence through John Zorn’s label Tzadik as part of the New Music Japan series, it wasn’t necessarily in line with the work of other groups in the series such as Melt-Banana, but it’s what makes Under The Pipal Tree one of the finest love letters to the genre. Instead of defining it, it circles back on the work of Mogwai, gleans influence from Sonic Youth’s earlier releases, hues it with their own brand of melodic thrash.

Where Mono particularly excelled through their career was their ability to create some of the tightest builds and climaxes in post-rock. Even Pipal’s 12-minute opener ‘Karelia (Opus 2)’ sounds like a grand finale. Mono’s greatest asset was their ability to make you feel kaleidoscopically with each cut — and their commitment to it was so intense, the album could quite literally change your heartbeat with every new riff. CL

29. Pram

Helium

(Too Pure, 1994)

Midlands-based band Pram are conspicuously absent from the hagiography of ‘90s British indie. But though their influences were logical enough starting points for a group of their era – Sonic Youth, The Fall, Can, The Slits – the results were anything but the typical watered-down rehash of those punk references. With Rosie Cuckston’s faux-naive, Mo Tucker-esque voice and kitchen-sink-drama lyrics floating over far-out organ drones, Radiophonic transmissions, wiry guitar licks and some absolutely killer jazz/hip-hop inspired drumming from Andy Weir, Helium was the sound of a band tearing up the formula.

In hindsight there’s a clear comparison to be made with cosmic-kraut-psych adventurers Stereolab, but home in on the jolting jazz-fusion logic of ‘Blue’ or the rattling drums of ’Things Left On The Pavement’ and Pram slide into position as sorely overlooked post-rock outliers. CR

28. Long Fin Killie

Houdini

(Too Pure, 1995)

Long Fin Killie don’t have the name recognition of some other artists on this list, but don’t let that put you off. Houdini is one of the lost treasures of the post-rock era, effortlessly fusing the sublime ambience of Talk Talk and Bark Psychosis with the post-hardcore mania of Rodan and Slint. Led by Luke Sutherland (who ended up playing violin for Mogwai), Long Fin Killie’s vocals and lyrics set them up in stark contrast to the majority of the rest of the scene; hauntingly complex, they illustrated gay encounters and class and racial struggles with striking poignancy and a casual effortlessness.

“How they’d love to lynch you,” he laments on ‘Hollywood Gem’, on the surface a story about a black actor on Hollywood, but offering no shortage of home truths as he manipulates familiar fiction and metaphor. ’The Lamberton Lamplighter’, on the other hand, examines Sutherland’s unease when he’s propositioned by girls. “I seem to have a lot more time for guys,” he states, as if questioning his own identity. A lesser-heard part of the Too Pure canon, Houdini is as widescreen as Labradford without resorting to any of the usual post-rock tricks. It’s no wonder Sutherland ended up a novelist. JT

27. Jeniferever

Spring Tides

(Monotreme, 2009)

It’s an interesting contradiction that despite the typical language attached to post-rock – cliches like “glacial”, “soaring” and “mountainous” paint a picture of a music mysteriously at one with nature – most of its bands actually came from urban spaces. Not Upsalla’s Jenifever, though, whose swirling sound seemed a genuine reflection of the snow-bound winters and lush summer vistas of their Swedish home city.

Their formula was smart: taking the vastness of post-rock and chiselling it into leaner, more urgent songs led by whispery vocals, they peaked with 2009’s Spring Tides, a record full of drama which teetered between beauty and something darker. Frontman Kristofer Jönson’s production saw the band return more muscular than on breakout album From Across The Sea, but it’s Spring Tides‘ frailest moment, the Ólafur Arnalds-ish piano and organ ballad ‘St Gallen’, that really stops you in your tracks. Just don’t call it “glacial”, okay? AH

26. These New Puritans

Field Of Reeds

(Infectious Music, 2013)

Field of Reeds is one of only a few records that could claim to be a successor of Talk Talk’s majestic strand of post-rock. The Essex band’s stunning third album abandoned the kinetic aggression of its predecessor, Hidden, for a sense of tranquility and space partly inspired by the liminal wetlands of their home county. They even hired Bark Psychosis’ Graham Sutton, a mastermind of early British post-rock, to supervise the recording.

Weaving together a spectrum of voices – from jazz singers to children’s choirs to the lowest male bass – with skeletal piano, brass, a magnetic resonator piano and even the sound of a hawk flying across the studio, Field Of Reeds is the work of obsessive minds who’ve let go of rules and expectations. CR

25. Tarentel

From Bone To Satellite

(Temporary Residence Limited, 1999)

San Francisco four-piece Tarentel are among the lesser-known names on this list, but they left an indelible mark on the post-rock genre, straddling its various strains expertly and exploring a variety of sounds. Their first proper full-length, From Bone To Satellite, is a stunning document of the genre at its long-winded best. There are only five tracks in total, and not one tracks clocks in at under 10 minutes. (One of them, the album’s blissful centerpiece ‘For Carl Sagan’, is over 20 minutes long.)

It’s hardly easy listening, but Tarentel do an expert job of keeping things gripping, utilizing krautrock influences on the motorik ‘Ursa Mino, Ursa Major’, noise and drone on ‘For Carl Sagan’ and Melvins-esque splatter on ‘When We Almost Killed Ourselves’. Somehow it all holds together masterfully, bridging the gap between the Chicago set’s jazz-flecked experimentation and Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s dense, harmonic drones. JT

24. 65daysofstatic

The Fall of Math

(Monotreme Records, 2004)

Oxford was a surprising hotbed for post-rock bands prodding at the genre’s boundaries in the early ‘00s. Before British indie stars Foals (now found entertaining arenas) there was The Edmund Fitzgerald, a trio featuring vocalist Yannis Philippakis and drummer Jack Bevan, who took post-rock structures and dynamics and slung them into brittle, reverb-less compositions that nodded to Chicago weirdos Sweep The Leg Johnny. Regularly on bills with them were Youthmovies, who jerked between post-rock ambience and math-y madness on their cult Hurrah! Another Year… EP.

But the band that broke out from this scene was 65daysofstatic (actually from Sheffield, but always seemingly always at Oxford venues with the aforementioned bands). Braiding glitchy electronics with Explosions In The Sky’s guitar rise-and-fall crescendos, their 2004 debut album The Fall Of Math wasn’t subtle, but it was effective. ‘Retreat Retreat’ remains a Mogwai-ish belter lit up by ghostly synth yawns, while the skittering beats and piano of ‘The Last Home Recording’ nod at a more restrained, sophisticated band to come. They’re now soundtracking 2016’s most anticipated video game, space adventure No Man’s Sky. Returning to The Fall Of Math, it’s hard to think of anyone better for the job. AH

23. Moonshake

Eva Luna

(Too Pure, 1992)

While British band Moonshake pre-dated the “proper” post-rock scene by a couple of years, their experimentation undoubtedly informed what was just around the corner. Blending the misty haze of dream pop and shoegaze with ideas (including their band name) cribbed from Can and the krautrock scene, the band’s approach was to throw everything into the mix and see what happened. This proved successful, and Eva Luna sounds prescient even now with its soupy fusion of flavors and techniques.

Moonshake ended up evolving into Laika, who made it into our best trip-hop albums list but could easily have been included here too. That should give you some indication of just how expansive and boundary-pushing their sound was. They might not have shared the loudness or riffing of their later peers, but their experimentation captured the very essence of the genre. JT

22. Twenty-Six

This Skin Is Rust

(Bobby J, 1996)

Listening to This Skin Is Rust is like inspecting an empty chrysalis; as well as being shabby evidence of the previous incarnation of Johnny Jewel, Drive composer and linchpin of synth-pop bands Chromatics, Glass Candy and Desire, the album was released by Todd Ledford, the astute listener who went on to found Olde English Spelling Bee.

The solo Jewel dabbles in swirling, moody guitars (‘Unbound’), miserable poetry spoken over organ drones (‘This Skin Is Rust’) and Jandek-style acoustic deconstruction (‘Astorone’) in his more obviously post-rock moments, but the glassy drones of ‘One Exit’ and the spidery piano on ‘The Coldest Day’ are closer to noise/ambient territory. Either way, the mood is fittingly bleak and autumnal; Jewel is picking over the carcass of rock and making small gestures with the debris, an approach that unites so many albums on this list. CR

21. Fly Pan Am

Fly Pan Am

(Constellation, 1999)

Constellation’s stranglehold on post-rock is undeniable, but Fly Pan Am were always the label’s black sheep. Leaning more toward avant experimentalism than their counterparts in Godspeed!, their sleek Pan Am airlines imagery bled into their double-disc debut. A paean like ‘Et aussi l’éclairage de plastique au centre de tout ces compartiments latéraux’ both encompassed the values of post-rock while becoming a literal interpretation of a luxury airline’s fraught reality.

They also prefigured their future work with artists like Tim Hecker on ‘Nice est en feu!’, a dark hymnal that ditched instrumentalism for uncanny choir vocals – an element that should evoke beauty at the conclusion of such a lengthy record, but is also slightly unsettling. Fly Pan Am especially works as a debut because it catalogues the group’s willingness to push outside the comfort of Constellation, hinting that even though post-rock is a total outsider’s playground, it can get that much weirder. CL

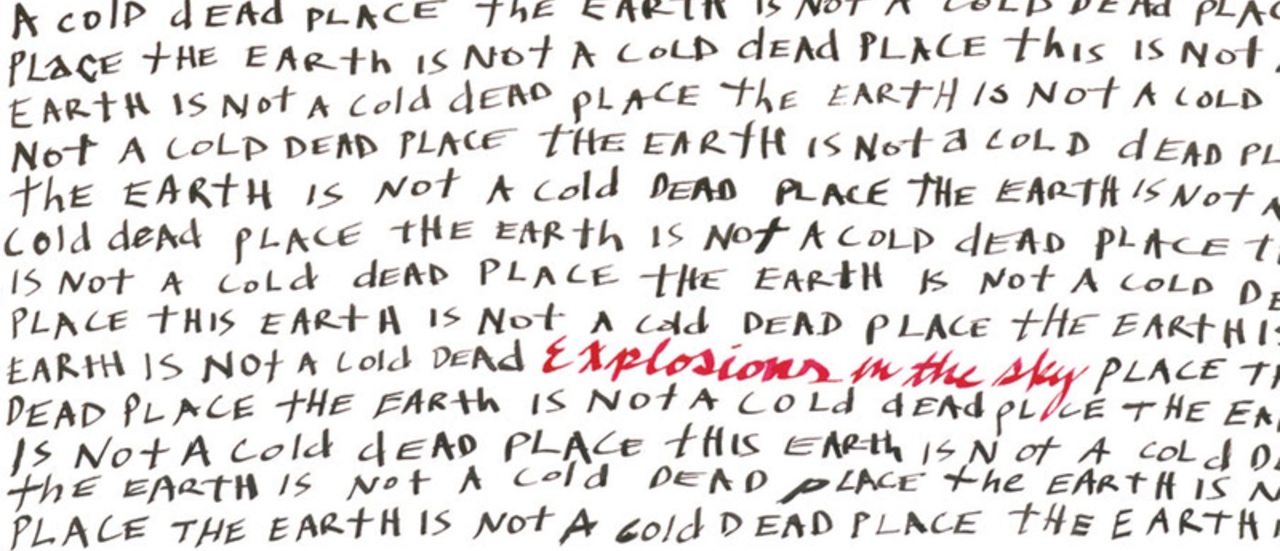

20. Explosions in the Sky

The Earth Is Not A Cold Dead Place

(Temporary Residence Limited, 2003)

At a decidedly gloomy time in US history, with the clouds of the September 11 attacks still yet to disperse from the American psyche, Texan instrumentalists Explosions In The Sky released a career-best album that was defiantly, almost shockingly optimistic. From airy opener ‘First Breath After Coma’ to the arresting ‘Your Hand In Mine’, the album benefitted from spacious production by John Congleton, frontman of dissonant rockers The Paper Chase and now a Grammy-winning studio mastermind who works with St. Vincent.

Full of bright melodies and chiming delay pedal guitars, Explosions’ simplicity on The Earth Is Not A Cold Dead Place is what made that album great, but also damned them in years to com; as the record became a post-rock favourite, their blueprint was easy to replicate, creating a sea of diluted copyists. But there’s no taking away the sparkle of the album that inspired them all. AH

19. Do Make Say Think

& Yet & Yet

(Constellation, 2002)

Toronto during the 2000s was home to a certain sound, full of warm indie guitars, homey production and honeyed ambient leanings: Broken Social Scene had it, American Analog Set had it, and so did Do Make Say Think. The five-piece’s floaty, jazz-influenced post-rock incorporated brassy interludes and math-y rhythms that jerked song sections in and out of time, delivered best on & Yet & Yet, their fourth album.

From opener ‘Classic Noodlanding’ to the jittery ‘Reitschule’, drummers James Payment and Dave Mitchell (yes, drummers plural) led the way, their polyrhythms like building blocks with melodies added around their hypnotic, upbeat sway. The album’s sweetest moment ‘Soul and Upward’ might not be the best-loved Do Make Say Think track (2007’s ‘A Tender History In Rust’ probably takes that accolade) but it arguably sums up better what they do best: songs soaked in joy, in a genre better known for contemplating darkness. AH

18. Aerial M

Aerial M

(Drag City, 1997)

If post-rock has anything close to a central figure, it’s David Pajo. The multi-instrumentalist has been a presence from before the genre’s inception, playing with core bands Slint and Tortoise before taking its influence further afield, going on to play and record with Will Oldham, Billy Corgan’s Zwan project, Stereolab and even Interpol. Despite his appearances on wildly varying projects, it’s Pajo’s vast solo catalogue where his talent as a musician really shines, proving just how vital his role was in shaping the sound of post-rock.

Aerial M is his first solo album, and was released just a year after he joined Tortoise for Millions Now Living Will Never Die. Even by the standards of a genre known for its introspection, the self-titled LP is a tender affair with a more homespun, confessional feel than other post-rock records from the era. With Pajo playing all the instruments, it’s easier to appreciate the sudden shifts in volume that mark out his signature – a style that’s been imitated by many but never bettered. SW

17. Stars of the Lid

The Tired Sounds of Stars of the Lid

(Kranky, 2001)

Compared with what we think of as the primary idea of post-rock — using standard rock instrumentation to explore compositional unknowns — Austin’s Stars Of The Lid reached into the unknown. The drone legends dissolve standard guitar lines into sonic incense, creating symphonies as structurally abstract as they are emotionally affecting.

The Tired Sounds builds out an entire world with glacially processed guitar, weeping strings and dreamlike field recordings. After a tender climax in ‘Requiem For Dying Mothers’ dissipates, they reach an intimate coda through the sample of a crying dog. It’s choices like that which make each atmospheric vignette so compelling, from the mini-suites ‘Austin Texas Mental Hospital and ‘Broken Harbors’ to the brief, evaporating ‘Fac 21’. And for anyone dismissing it as simple ambient music, a trip to one of their titanic, humbling live shows reveals just how brightly these stars burn. MB

16. Rachel’s

The Sea and the Bells

(Quarterstick Records, 1996)

Classical instrumentation is an important feature for several post-rock acts, but usually as a backdrop for their guitars. Rachel’s was different. Formed in 1991 as a side interest to his role as guitarist in Rodan, Jason Noble’s ensemble quickly gathered a cast of collaborators including violist Christian Frederickson and pianist Rachel Grimes, both of whom quickly became the focus of the band’s emotive sound, influenced partially by modern composers like Michael Nyman and Angelo Badalamenti. Guitars feel so absent from Rachel’s it feels almost wrong to call them post-rock at all.

Recorded in 1995, the emotional heft of The Sea and the Bells is made all the more poignant by the early death of Noble in 2012 from cancer. The album’s instrumentation gives it all the gravitas you’d expect, but where a band like Godspeed You! Black Emperor use their strings to create desolate, cinematic landscapes, The Sea and the Bells is a much more intimate experience. It’s probably why the band’s music has been used on several films: it connects with simple human emotion in a way that many of the their more technical contemporaries don’t. SW

15. Directions

Directions in Music

(Thrill Jockey, 1996)

As a founding member of both Tortoise and Gastr Del Sol, Bundy K. Brown is a tower of the post-rock community. When he left Tortoise amicably in the mid-90s, he recorded a single album under the name Directions, and while it remains less well-known than, for example, Tortoise’s Millions Now Living Will Never Die, which emerged at around the same time, it remains one of the jewels of the entire genre.

Knowing Brown’s contributions to the scene, the sound of Directions In Music shouldn’t be a surprise: swooping guitar textures, tight rhythms and memorable, even catchy melodies, but the indulgence that inevitably killed the genre is nowhere to be found. The album sounds exploratory in the best way, as the trio use the studio as an instrument, manipulating instrumental parts masterfully and emerging with a record that needs to be listened to from beginning to end to get the full picture. JT

14. Hood

Cold House

(Domino, 2001)

Radiohead’s Kid A felt groundbreaking to many listeners, but for some of us it just didn’t go far enough to integrate electronic sounds with the regular “rock band” aesthetic. Hood’s Cold House, on the other hand, went all the way, as the band punctuated their whimsical Northern indie with electronic rhythms and glassy synthesizers that could have been snatched from an Autechre EP.

At times it almost sounds like Talk Talk and Aphex Twin playing simultaneously; ‘You Show No Emotion At All’ retains the backbone of a real song, but layers bitcrushed beats far more successfully than ‘Idioteque’ ever did. The Leeds-based crew didn’t just stick to the same tricks either – experimentation was at the very heart of their sound, as they folded in chopped breaks and Notwist-esque elements on ‘Enemy of Time’, abrasive microsound on ‘The Winter Hit Hard’, and even invited experimental rap troupe cLOUDDEAD to guest on ‘Branches Bare’. If post-rock was often about studio experimentation, Hood were out there on the front line, and Cold House stands as their most pristine statement. JT

13. Thee Silver Mt. Zion Memorial Orchestra & Tra-la-la Band

Horses In The Sky

(Constellation, 2005)

“They put angels in the electric chair, the electric chair, the electric chair,” begins the Montreal crew’s 2005 zenith, and it only gets bleaker from there. It made sense that as the ‘00s progressed, the fiercely political collective at the heart of Godspeed You! Black Emperor placed more stock in their lyric-led side-project; as the mood in post-9/11 North America grew grimmer, reluctant leader Efrin Menuck had more to say, statements that could no longer be hid simply in the atmosphere and aesthetic of Godspeed instrumentals.

Horses In The Sky saw them tear up a gear. Opener ‘God Bless Our Dead Marines’ had titular nods to America’s war-mongering in Iraq and asked in heartbreaking choral vocals how it’s possible to live a normal life while hospitals and schools are being blown to bits far away (“When the world is sick, can no one be well?”). Efrin finds an answer later on: our best bet, he and his band mates say, is to “hang on to each other”. A still-stunning moment at the most baroque end of the post-rock spectrum. AH

12. Main

Dry Stone Feed

(Beggars Banquet, 1993)

Though not strictly post-rock, Loop’s Robert Hampson and Scott Dowson were experimenting with the rock formula – disintegrating their sounds with studio trickery and doing so at the loudest possible volume – before and after post-rock was a concern.

1992’s Dry Stone Feed is possibly their most important contribution, as it cribs from industrial and ambient music but still retains that all-important rock backbone. Vocals tumble over glassy sheets of guitar noise and tight, workmanlike beats, and everything is obscured by an echoing haze. There’s no quiet-loud here – Main start as they mean to go on, and Dry Stone Feed is destructive from beginning to end. JT

11. Disco Inferno

The 5 EPs

(One Little Indian)

This compilation of five EPs – Summer’s Last Sound (1992), A Rock to Cling To (1993), The Last Dance (1993), Second Language (1994), and It’s A Kids World (1994) – demonstrates how Disco Inferno went where very few rock bands in the early ‘90s dared to go — towards the digital frontier. The Essex trio (who began life as a four-piece) wove off-kilter samples and found sounds like church bells and shattered glass through echoey monologues and barely-there guitars, offering up pseudo new-age lullabies resplendent with birdsong, running water and kitchen sink rhetorics,, as well as dreamy post-punk.

The fact that Disco Inferno were making music in thrall to US hip-hop and with some experimental heft at a time when pedals were all the rage in traditional guitar circles gives them an almost unearthly, untouchable quality, while the record itself is marked by its intense, trencadis-like tangibility. ACW

10. Gastr Del Sol

Camofleur

(Drag City)

Gastr Del Sol’s swan song Camofleur found David Grubbs and Jim O’Rourke re-approaching conventional song structures after having broken them down to microscopic level with their previous albums. The result blends their most dynamic experiments with their catchiest writing — granted, “catchy” is relative when you’re talking about a record produced by Markus Popp not long after Oval’s glitch masterwork 94 Diskont. ‘The Seasons Reverse’ explodes with ideas, letting dizzy percussion loops, steel drum and blaring organ and brass crash against each other while Grubbs’ surreal poetry skips over the top. The coda reveals drum claps to be children lighting firecrackers, recorded by O’Rourke and interrupted when they get wise and approach him.

‘Blues Subtitled’ playfully showed how Grubbs approached lyrics the same way many of his Chicago contemporaries silently pursued instrumentation. It’s also the pair’s best guitar record, pushing their always dense interplay to overwhelming complexity with the acoustic wormholes of ‘Black Horse’ and the closing ‘Bauchredner’. That final goodbye builds an almost suffocating degree of tension with simply overlapping guitar lines before locking into a surprisingly traditional rock finale. It’s like one final twist — they could play like anyone, but chose to sound like no one. MB

9. Sigur Rós

Agaetis Byrjun

(Smekkleysa, 1999)

Reykjavik’s Sigur Rós are a band you could credit with post-rock’s rise and, perhaps inadvertently, its fall as well. By the time they released their fourth album Takk in 2005, everyone from Formula 1 ad makers to BBC documentary teams had realised the soundtrack potential of their drifting, otherworldly compositions. What followed arguably sanitised post-rock: from fringe beginnings, post-rock songs and their bad rip-offs were suddenly everywhere, reducing the genre to a type of TV Muzak. A music that was born with a certain anti-commercial defiance, stretching out over long tracks which would rarely make it anywhere near mainstream radio, ironically ended up the music of commercials.

By the late ’00s, there was a sense that post-rock was no longer beloved by critics the way it once was. But you can’t blame Sigur Rós for that. It wasn’t really their doing, and even if it was, anything is forgivable after you’ve delivered the world an album like Ágætis byrjun. Their second album saw huge innovations: frontman Jónsi Birgisson began bowing his guitar like a cello, and the new sound put the world outside your headphones into dramatic slow motion. ‘Ny Batteri’ saw him sing above a bed of stately horns and melancholy bass till everything around him was noise, while ‘Staralfur’ should be listed in medical journals as a cure for high blood pressure, such is its immaculate, untouchable calm. It’s a record many would have expected near the top of this list, and understandably so: Ágætis byrjun, sung in the made-up tongue of Hopelandic, used not just a new lyrical language but a musical one too. AH

8. Labradford

Mi Media Naranja

(Kranky, 1997)

Founded in 1991, Labradford were key players in the post-rock movement even if they remain somewhat unsung heroes of the genre. Their widescreen vision, sweeping the sounds of Ennio Morricone and Arvo Pärt into a post-rock template that was still in its formative stages, characterized a whole section of the scene, influencing a swathe of young artists, rock and otherwise.

Mi Media Naranja is undoubtedly the band’s high point, building on the smudged drone of their first few albums and giving it focus, restraint and an incredible layer of detail. Their influences are sometimes stripped back to the tiniest elements – the light rhythmic thud of dub in ‘G’ or the subtle electronic treatments of ‘I’ – only revealing themselves on repeat listens.

It’s one of the most subtle records on the list, a direct descendent of Laughing Stock and Hex rather than Spiderland, and almost gets better with age. Nothing sounds dated or overdone almost two decades later. It’s beyond trite to call an album a “soundtrack to a nonexistent movie”, but in this rare case it’s entirely fitting. JT

7. Godspeed You Black Emperor!

F# A# (Infinity)

(Constellation, 1997)

Montreal’s sprawling, anarchic collective are to post-rock what death and locusts are to the end of the world, and with an opener like “The car’s on fire and there’s no driver at the wheel / And the sewers are all muddied with a thousand lonely suicides,” it’s no wonder Danny Boyle chose to feature the band’s 1997 debut in his post-apocalyptic horror 28 Days Later.

The idea that with an artistically placed guitar line here, or a brush-stroked drum pattern there, post-rock instrumentation can paint sweeping, vivid landscapes is at its most pronounced on Godspeed’s F# A# (Infinity). With string-led classical flourishes and mordant monologues cut up like a Williams Burroughs novel, the record’s creeping sense of doom is offset by the kind of widescreen, ambient dreamscapes that usher in sentiments of peaceful respite. A little like drowning euphoria, probably. ACW

6. Mogwai

Young Team

(Chemikal Underground, 1997)

You can’t talk about post-rock without mentioning Mogwai, the Scottish four-piece who helped propel the genre into the mainstream. When they burst onto the scene with a handful of splits and 7”s, their hype was often written off by cynical journalists who had them pegged as Sonic Youth or Slint copyists. Certainly the fingerprints of their influences were visible on their early material, but with their debut album Young Team they forged their own unique identity, helping create a fresh blueprint for post-rock and sparking two decades of experimentation.

Young Team holds up too, sounding as enjoyable, weighty and as crushingly dense as it did back in 1997. It kicks off with the Slint-ish ‘Yes! I Am A Long Way From Home’ but quickly settles into its own groove, tumbling into the raucous ‘Like Herod’, a fan favorite that’s among the heaviest tracks Mogwai have ever committed to wax. It’s not all quiet-loud though: gorgeous, piano-led ‘Radar Maker’ offers welcome respite and ‘Tracy’ finds the band settling into a sound they would expand on over the next few albums, all soupy harmony and chiming melancholia.

What set Mogwai apart from their peers was their charm and humour – the young team were growing up on record, wearing their hearts on their sleeves and sprinkling their distinctly Scottish identities over a sound with its roots on both sides of the Atlantic. By the time we reach the album’s crushing finale – ‘Mogwai Fear Satan’ – there should be no doubt in your mind that Young Team is one for the ages. JT

5. Rodan

Rusty

(Quarterstick Records, 1994)

Before Rusty was even a glimmer in its players’ eyes, it was primed to be one of post-rock’s greats. What do you do when you’re prepping a math-rock debut that could potentially go on to be a classic? You get the guy who gave Steve Albini a hand engineering Nirvana’s In Utero, Bob Weston, to produce the thing. (The album was titled after his nickname as well.)

But where Weston’s work with Shellac is known for being as confrontational as possible, he guided Jason Noble, Jeff Mueller, Tara Jane O’Neil and Kevin Coultas to explore every inch of how that confrontation can be expressed. Rusty deals largely with the void — the quiet beauty of languishing in the calm and the emotional density of throwing all of that away. What is immediately evident on the record’s opener, ‘Shiner’, is that Mueller and Noble weren’t necessarily in competition, but that they were going to design guitar lines that taunted each other. Their riffs may have sounded disparate, but paired together, they made sense out of chaos.

And yet so much of Rusty is uninhabited. ‘Tooth Fairy Retribution Manifesto’ just stops. It just fucking stops. And what math-rock, post-rock and other sound-building genres sort of have the responsibility to do is coax its listener out of the wall of din without making her heart stop with abrupt finishes. But Rodan didn’t care. If the blueprint for math-rock had already been laid out, Rusty was an exercise in erasing some of its buttresses. Both Noble and O’Neil went on to make some of the most important and interesting alternative music of the last 30 years, but without the deconstruction instructions they authored with their debut, others might not have been able to keep up. CL

4. Talk Talk

Laughing Stock

(Verve Records, 1991)

Talk Talk spent the late ‘80s spending EMI’s money on the perverse dismantling of their glossy avant-pop formula, which had delivered them huge, and somewhat unlikely, commercial success earlier in the decade (who else on this list has written anything remotely as catchy as ‘It’s My Life’?). The shock came first on 1988’s Spirit of Eden, with six tracks, not one of them offering itself as a hit single, and a starring role for the group’s favourite new instrument: silence.

Frontman and artistic dictator Mark Hollis pushed his vision to the absolute limit on its follow-up, which proved to be their swansong as a group. Laughing Stock was recorded over a year in an intense and seemingly debilitating atmosphere, with clocks removed from the studio, oil projections on the walls and no other light apart from a strobe, as noted in Wyndham Wallace’s excellent autopsy of the album’s making. Most of the music they recorded was binned as Hollis pieced together his magnum opus from hours of improvisation, attempting to capture the spontaneity of his jazz heroes.

In a certain light, Laughing Stock is obviously the odd one out in a list of post-rock albums. Talk Talk come from a very different world to that of Mogwai, Labradford or Stars of the Lid, with synths rather than rock guitars defining their early pop sound. But from the long hiss of a waiting amplifier that opens ‘Myrrhman’, it’s obvious that Laughing Stock pivots on many of the same elements as the nebulous post-rock sound. Song structures are loose and unpredictable, with organ drones, echoing guitar and murmured vocals following their own meandering trails, congealing into epic climaxes and falling away to reveal huge chasms of silence. Take the one-note guitar scree that carves up ‘After The Flood’, a savage inversion of the virtuoso indulgence of classic rock, or the crashing drums that build a wall of sound at the end of ‘Ascension Day’. And like so many records on this list, beneath the musical experimentation lies a deep melancholy; an earnest, introspective mood that’s rarely been more clearly expressed than in Hollis’ quivering vocal performance. CR

3. Tortoise

Millions Now Living Will Never Die

(Thrill Jockey, 1996)

With seven albums recorded over a 26-year career, Tortoise are practically establishment figures. Prior to the Slint and GY!BE reunions, Tortoise were the tentpole band for early attendees of ATP festival (RIP), and they continued to fly the flag for the genre through the 2000s. Tortoise never had the mystique of a band like Talk Talk or the sonic power of an outfit like Mogwai, but no band operating in the post-rock sphere stretched the boundaries of the genre in quite the same way.

Millions Now Living Will Never Die stands as the band’s high point. Recorded two years before Jeff Parker brought a strong jazz influence to the band on TNT, it catches Tortoise as they start to expand on the scale of their self-titled debut, but before they get stuck into the looser, more improvisational structures of their later albums. The 20-minute opener shows just how ambitious a band they were so early on, moving through motorik grooves, dub and a minimalist passage reminiscent of Steve Reich’s ‘Music For 18 Musicians’.

When ‘Djed’ finishes, the album’s remaining five tracks pass in a flash. It’s partly due to their short length, but primarily because Tortoise play with an energy that that’s closer to math-rock than post-rock. Their sharp guitar lines hit you with velocity rather than brute force, despite the relaxed, almost languid mood their music evokes. A combination of rock and lounge music doesn’t sound all that appealing on paper, but it’s this lack of pretension that makes Millions Now Living Will Never Die so compelling, even now. SW

2. Slint

Spiderland

(Touch And Go, 1991)

Slint released the now-iconic Spiderland in 1991 while still a bunch of Kentucky nobodies. People couldn’t find out anything about them: by the time the album was released the band had split ways, meaning no interviews, and at a time where there was of course no internet for online sleuthing. And so four young scrappers in baggy shorts from Louisville, Kentucky became for a period the most mythical band in America.

The cloud of mystery that surrounded them as Spiderland became a word-of-mouth monster, paired with the dark, obtuse intensity of their music, meant that all kinds of rumours sprung up about them: band members living in psychiatric wards; recording sessions that drove them to the brink of destruction. Slint and Spiderland were products of their time in this way. They, and post-rock as a whole, thrived on a sense of intrigue less feasible in today’s internet age. Which made founding member David Pajo’s public collapse last year all the more strange and upsetting to witness – an artist whose musical life had been largely spent collecting acclaim in the shadows was now falling apart in the cold, clinical light of social media.

The guitarist is thankfully now on the mend, despite having suffered a motorcycle accident earlier this year. For selfish reasons, that’s just as well: Spiderland’s grappling with love, death and mortality might be too poignant to bear had one of the driving forces of it passed away so tragically. And what a record it would be to no longer endure listening to. There was little like it before, and there has been little like it since: hardcore guitars, labyrinthine narrative tales delivered in sober spoken word, math-y rhythms, all climaxing with pained shrieks of “I MISS YOU!” on final track ‘Good Morning Captain’.

Although Slint were only accidentally post-rock, in a lot of ways Spiderland is the definitive post-rock album. The way ‘Nosferatu Man’ looks to 1920s German expressionist cinema for inspiration is exactly the kind of intelligence the genre was born to bring to guitar music, proving after all the sexed-up pomp of the ‘80s that rock could have artfulness again. Its cover, shot by Will “Bonnie Prince Billy” Oldham, saw the band bobbing above water in an abandoned quarry. It was the perfect metaphor – an invitation. From its opening chimes, Spiderland is like being submerged in a totally different world. AH

1. Bark Psychosis

Hex

(Circa, 1994)

It seems fitting that our number one album should be Hex, the record which, as legend has it, was the first to be described as “post-rock”, in a review by journalist Simon Reynolds. Writing for Mojo in 1994, he described Bark Psychosis as “futurists” who were operating on the fringes of the scene at the time, linking unusual influences in very new ways. Sadly this wasn’t actually the first use of the term (it wasn’t even Reynolds’ first time using it), but it did give a name to something formless, a scene that would come to (sometimes inexplicably) bind a number of disparate sounds.

The term feels particularly applicable where Bark Psychosis are concerned. Graham Sutton and John Ling’s band began inauspiciously enough in the thrall of noise rock, thrashing through Napalm Death covers and eventually deciding on a Swans-influenced post-hardcore sound. Noise, however, felt like a creative dead end for Sutton and Ling, and their experiments recording in the crypt of Stratford’s St John’s Church (which they used as a makeshift studio) led to something truly transformative.

After a few singles, their sound came starkly into focus on 1992’s Scum, a single-sided 12” that felt like a massive “fuck you” to the established rock world. The cover was a photograph of a pocket blade and the record’s “etched” side was roughly scored with a knife – this meant something. The record emerged from a 10-day session in the crypt, and was Sutton’s reaction to the insincerity of mainstream music. “I just remember this one track had this chorus like ‘Everybody’s free’ and it made me want to fucking puke,” he recalled in a 1994 interview. The resulting 21 minutes of music was the antithesis, built around drones, samples and soundscapes, and more indebted to Talk Talk’s Spirit of Eden or Brian Eno’s On Land than anything particularly contemporary.

The 12” was something of a success, achieving Single of the Week title in Melody Maker, and as it gathered traction the band began to record Hex. It wasn’t an easy process by any means – Sutton was becoming obsessed with electronic music and had abandoned the guitar in favor of a sampler. Stubborn and single-minded, he admits that the year recording Hex was stressful, and indeed it led to two members (John Ling and keyboardist Daniel Gish) burning out and quitting (although Gish would later return as a guest for live shows).

Somehow, the finished product makes it all worthwhile. Sutton managed to imbue the soundscapes he’d perfected on Scum with the heart (and occasionally hooks) of proper songs, and on tracks like the epic centerpiece ‘Absent Friend’ and the dubby ‘Big Shot’ set a new standard for a genre that was still in its infancy. Sutton appeared to be breaking the songs apart and rebuilding them into fractured, ghostly traces – a throwaway sound from a studio rehearsal might be pulled into the foreground, while shimmering reverb is all that remains of that all-important lead guitar part that would have sat at the very center of most mixes.

Hex is an album that can truly be called post-rock. Sure, the term has gone on to become synonymous with the euphoric quiet-loud aesthetic of Sigur Rós or early Mogwai, but when describing Bark Psychosis, it’s truly fitting. Hex took rock’s structures and burned them down, rebuilding them in the studio with mismatching pieces. The result is still completely jaw-dropping. JT