Signal Path is a new series that delves into the studio processes of some of our favorite producers and musicians. In this first interview, Scott Wilson talks to Simian Mobile Disco about two decades in music, from buying their first used synthesizers to working with a choir for their most recent album, Mumurations.

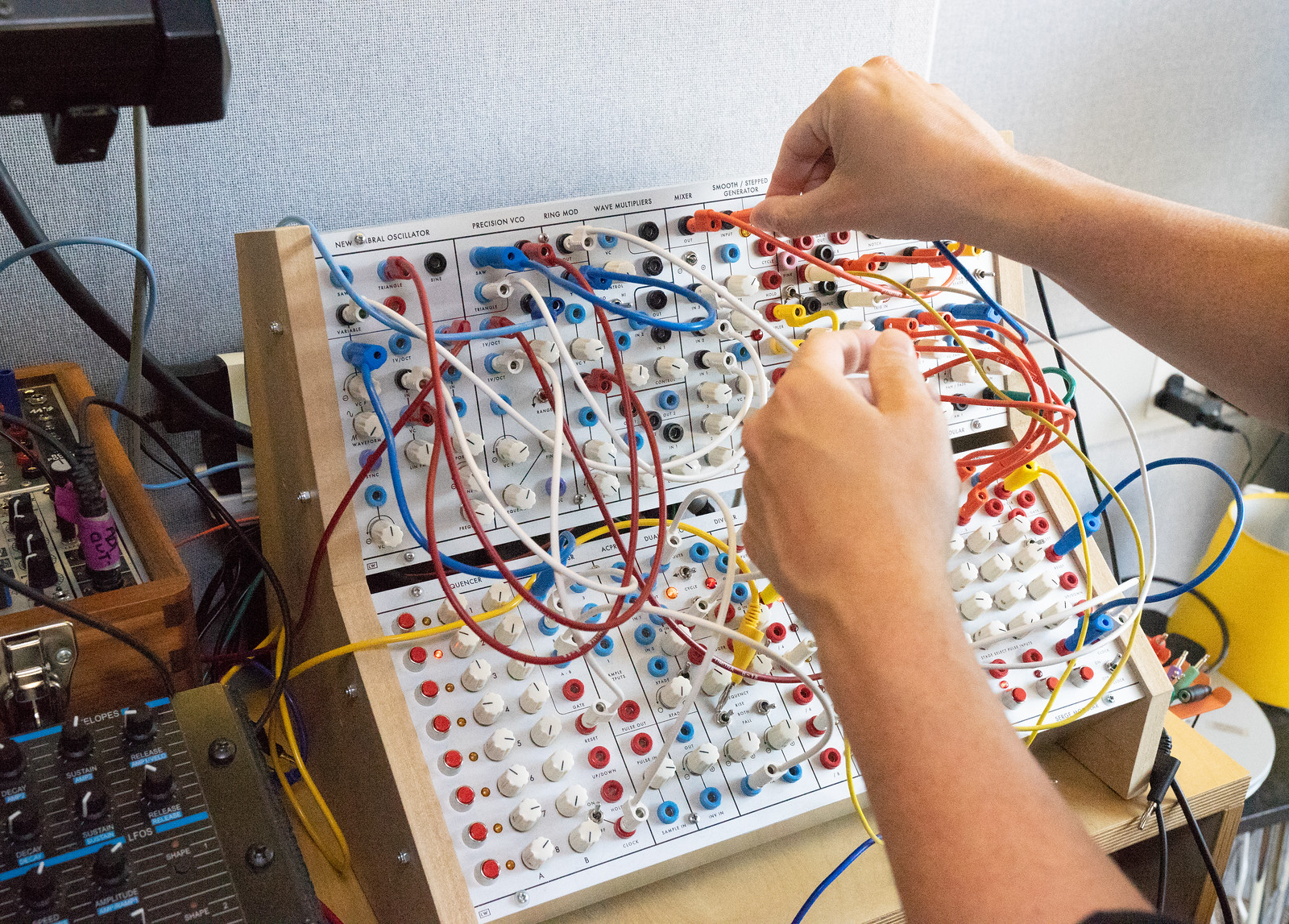

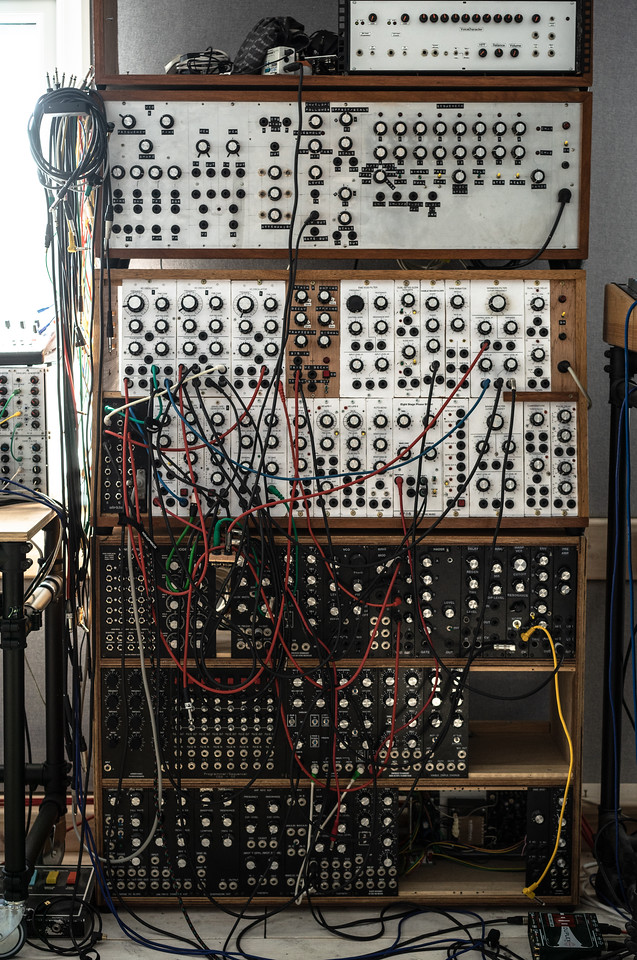

The first time I ever saw a modular synth being used on stage was when Simian Mobile Disco played Glastonbury in 2007. At the time, I had no reference for what I was seeing; James Ford and Jas Shaw – fresh from the release of their debut album Attack Decay Sustain Release – looked more like mad engineers conducting an experiment than musicians, circling a towering stack of gear and patch cables, tweaking knobs to make an array of bleeps and squelches. It left a huge impression on me: what were they using, and how were they making music with it?

Ford and Shaw could have easily let their modular system become their on-stage gimmick, a spectacle to match the bombastic light shows of contemporaries Justice and the burgeoning EDM scene. Instead, they focused on studio science, switching up their practice with every record. From the pop crossover of 2009’s Temporary Pleasure to 2014’s stripped-back Whorl – which was recorded on a very limited selection of modules – the duo have sought to challenge themselves in different ways.

Their latest record, Murmurations, is the duo’s biggest step outside of their comfort zone yet. A collaboration with London’s all-female Deep Throat Choir, the LP is loosely based around the human voice; the 4/4 techno pulse that runs through their discography is still present, but here it feels like more of a jumping off point for exploring texture, timbre and harmony than for soundtracking a rave. Like Temporary Pleasure, Murmurations is a pop album at its core – albeit one that’s inspired by Moondog and the flocking of starlings.

When I speak to Ford and Shaw about their music-making practice over the phone in their respective studios – Ford at his home attic space in London and Shaw at his studio in the English countryside – I find out that despite the album’s vocal focus, synths are still very much part of the process. Our conversation takes place shortly after Shaw’s diagnosis with AL amyloidosis, a rare, potentially life-threatening condition that affects organ and tissue functions that forced the duo to cancel a US tour while he receives chemotherapy. Despite low energy levels due to his treatment, Shaw is sharp and in good spirits. “It’s not really changed anything,” he says, “but it’s certainly brought [my work] into focus.”

What inspired you to make an album around the human voice?

James: “The thing I find about voices is that there’s just an instant connection to other humans. You can listen to music totally outside your own culture and you can still connect to it if there’s a voice and a person behind it. I think there’s something inherently powerful in that, so I’m always interested in using voices, but there’s a rub you get with electronic music where they don’t necessarily fit very easily, especially with the route that we’ve gone down – we’ve found it harder and harder to incorporate voices at all because they weren’t really exciting us or doing the things we wanted them to do.

“We were thinking of different ways to use voices and a friend of ours sings in the choir and thought it might be an interesting way to approach melding the human voice with electronics and using voices texturally and more like an instrument – less straight up than the singer-songwriter vibe that we’ve explored in the past. I especially quite like the human voice – Jas is a little less keen on it!”

Jas: “Maybe that’s a little strong! I like voices the same amount as I like drums or synths. James is right, people immediately connect to voices and I don’t know if I ever have, but that doesn’t mean that I’m not interested in them at all. I think that it’s an area where we’ve done some things that worked really well, but it’s also an area where we’ve come completely unstuck, so I’m nervous of voices.

“The way we approach synths is we try and do it differently way each time, not to come back to the same old gear, the idea being that we approach whatever palette of sounds we have and feel really excited about it. So we wanted it to be a more compelling process than just getting a vocalist in – it was off-piste for both of us. It changes the nature of what a voice is when you’ve got a group of people singing, versus a single person.”

Is the album really themed around the emergent behaviors of starling cloud formations?

James: “The idea happened a bit more organically. It was actually in the studio with the choir; Luisa (Gerstein, Deep Throat Choir founder) had written a whole bunch of song-y, sort of lyrical ideas. When we went in, we spent at least 50 percent of the time doing procedural exercises that Jas and I had come up with. One of these procedural ideas was for them to pick a chord; we distributed it between the choir so they were all singing a different note and then we nominated two or three people in the choir to be ‘explorers’, who would deviate from the note within the key and move around and improvise.

“Once they’d gone off a bit their neighbor would follow them, harmonize with them and respond to them, then their neighbor would do the same and eventually the whole choir broke up into this sort of improvised ‘pad’. We listened to this unfold and it turned into this really beautiful thing that spontaneously changed chord; sometimes it ran more dissonant and sometimes more pretty. We thought it sounded like a murmuration of starlings – where it seems there’s an overall consciousness of birds moving together when there isn’t really – it’s just very simple little rules that lead to this big, complex behavior.

“This idea was really attractive to us because it sort of described a bit about the way we make music: using very simple elements, like sequences, where you get two or three of them interacting to make this more complicated thing, to bigger ideas about how nature works and simple mathematical rules of nature. So we just thought it was a nice all-encompassing idea for us to hang our coat on.”

You said you tend to use a few key synths or pieces of gear for each project. What did you use for Murmurations?

Jas: “One was an Oberheim Matrix James owns that he’s got controller for, which makes it fun to use. It has this really rich, wobbly, kind of spacey sound. And it’s polyphonic, which is pretty rare for the things that we have, so that integrated well with the choral stuff. There was a number of times where we would take these improvisations that we’d done in the studio and then we’d extract the notes from the session and stick them into the synth and then relate that to the vocals. Rather than writing something deliberately that would complement or expand on the vocals, it was like we were slaving the synths to the actual vocal improvisation; often there were notes in there that you probably wouldn’t have thought to put in – like a fuck-up in the recognition algorithms or something. But that in itself became a part of this slightly chaotic process.

“The other one is a Serge I just bought – it’s not actually a proper Serge, it’s a kind of DIY-type Serge. We were using that a lot for odd noise, because it excels in somewhat atonal stuff. Once you’ve got stacks of notes you want a bit of un-noteyness in there.”

James: “On each album we try and restrict the palette kind of quite consciously. So once we find an element that’s working – be it the Matrix the Serge or something like that – we tend to then try and use that for the rest of the record, because it instantly gives a bit of a ‘sound’.

“Another big element that we haven’t really used much before was live percussion. A lot of the rhythmic stuff that isn’t obviously synthetic is basically me and Jas in the studio hitting them. So there was conga, tambourine and just some random drums. One of the early touchpoints for the album was Moondog. It was a reference for the vocals because we like how loopy and childlike his vocal melodies are, but we ended up loving the sound of the percussion as well. There’s lots of roomy woodblocks and strange drums and timpani played into the tracks and either looped or left loose depending on how we wanted them.”

Jas, do you really not use polyphonic synths very much?

Jas: “No. I only have one, and it’s a (Roland) Juno. I would really like a properly programmable polyphonic synth, I just don’t really enjoy keyboards very much and they always have a keyboard bolted to the front, which immediately makes me quite suspicious of them. If I play a C minor shape then I’ll think, ‘that’s the worst thing I’ve ever heard, I don’t want to play with this ever again’. Whereas if you go up to a big pile of oscillators and you start tuning them and you’re not looking at the keys, you’re just hearing the interaction, which I think is a very different process.

“I remember like there was a track that we did, maybe on Unpatterns, which we did with my huge wardrobe synth with a step sequencer. We went through and we made what we thought was eight quite complicated chords that went around in an interesting way, and then for the live show we worked out what they were and it was really just two chords, inverted in lots of different ways. I think if we’d been doing it with our fingers we would thought we probably had to put a different note in there somewhere. But we weren’t – we were turning a dial, and I think it switches off that music analysis part of your brain.”

I sometimes feel the same way about keyboards – I often think “is this just a really basic chord to be playing?”

Jas: “Also with keyboards you can’t play the same note. A lot of what I like about guitars is when you play the same note on top of itself and it builds a kind of dominance on a note that’s not harmonically dominant. With keyboards it’s just one or nothing. There’s something about that I struggle with.”

Do you feel the same way about polyphonic synths, James?

James: “Sometimes when you take away the black and white keys and it’s more about the sound design and the sonics of it or the way notes interact, yes, you can definitely get much more interesting results. I definitely like chords and the way different melodies interact with each other and I do think there is a sort of magic in that as well, so I definitely enjoy that part of it too, but there’s not many songs that we’ve done in the past with chords on that I look back on and really like – maybe one or two. I definitely prefer it when we’ve gone a bit more off-piste.”

Do you remember how you first got into synthesis?

James: “I was about 14 I think and my Dad was in an amateur band. We had a cellar that had a crappy drum kit, a bass and a four track tape machine, and I would mess around trying to get a sound as close to a Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters as I could. I remember I was having guitar lessons from a guy whose little brother told me he was selling a synth for probably about £40 or £50, which felt like quite a lot of money at that age. It was a MaxiKorg, or a Univox it’s sometimes called, and it’s still one of my favorite synths. I just remember getting this thing and sitting in the basement and suddenly making all of these amazing, weird squelching noises that I’d never heard before and it being one of the defining moments in my childhood! And I’ve never looked back.”

What about you Jas?

Jas: “I don’t have anything approaching a touching story like that! I got more into synthesis via guitar. I was a guitar player for ages and got the pedal-buying bug – once you have enough pedals you just need any bit of input and then it pretty much just generates all the sound itself. I think that’s a pretty good primer for modular stuff – it’s really just the same but you have to use 9V batteries.”

Jas, Isn’t there an interesting story behind the first synth that you bought?

James: “I remember quite clearly at the end of Simian (the band), we thought ‘OK, well that’s it, this band’s over, let’s all go to get jobs or whatever’ and Jas spent what I thought was a crazy amount of money on a modular synth he found on Craigslist or Gumtree. And didn’t you go around and buy it from someone out of The Verve?

Jas: “Yeah.”

James: “And I was like ‘what is he doing’!? It was before all the Eurorack stuff became as popular as it is now, it was this niche thing. I remember being quite amazed and bemused that he’d done that. But we wrote most of the first SMD record with that synth.”

Jas: “Yeah, that particular synth was on the road for a decade and it’s still great, so I definitely don’t regret it, but I remember at the time it was three months rent that we spent on it and I went down there with my girlfriend at the time, who’s now my wife, and I plugged it in and showed it to her and she said, ‘it only makes one sound’. I think it was great. But maybe it was a bit rash.”

Did you really buy it from someone in The Verve?

Jas: “I did. I wanted to get into that stuff but even at the time it seemed unattainably expensive, so I looked on forums and some guy was selling a stack of it, so I went down there and it was Nick McCabe out of The Verve. As a kid I particularly loved the guitar on that first Verve album, so not only was I buying a life-changing synth but I was meeting a guitar hero, so I went back, pleased as could be!”

What kind of synths were you using at the time James?

James: “Well, I sort of kept on the Simian studio space so I kind of had all the remnants of what we had from being in in Simian, because I kind of had my eyes set on being a producer. I definitely remember the first synth we bought with Simian – we got some money from something and we bought a (Sequential Circuits) Pro-One. That was pretty much on everything we did as Simian. I remember one of the first things we did was a track called ‘The Wisp’, which has this kind of bubbly synth bass line with these little matrix glitches made because we didn’t really know what we were doing, but we thought sounded amazing.”

I really wanted to ask you about this wardrobe synth you bought Jas, because it’s a one-of-a-kind thing, right? Where did you get it?

Jas: “I actually originally bought it because I wanted to make a polyphonic modular synth but we virtually never used it as that. I found this guy who made this enormous synth – 5U format – and I think his wife said ‘it’s me or the synth’, so he put it up for sale. It was calibrated wrong, the gates went the wrong way and a fair bit of it didn’t work, but clearly for him it was a huge labor of love.

“We got it into the studio right around the first proper Delicacies record and I remember I would come into the studio and fix one module and use that or whatever else worked on the synth to make a track and then I’d fix another one. In that process we slowly worked our way through the synth. It is a pain in the arse because it’s really esotrical and wobbly and a lot of it just doesn’t quite work properly, but that’s also part of the charm of it.”

With two separate studios, how do you go about working on a new album, especially with gear in different places? Do you split your time between the two different spaces?

James: “Yeah, it’s quite good really to be able to have each different room surrounded by different equipment and speakers – it encourages you to make slightly different decisions, so it’s quite good for us to be able to flit between the two. I’d quite often go to Jas’s and stay there for a week or two and come home at weekends and then Jas will come out and stay with me for a bit and we’ll just do it like that. We never really work remotely. We tend to do it in the same room at the same time just because, again, it changes the things that you do. I think we’ve, we’ve spent so long working together, we’ve got a pretty fluid way of way of operating so it just seems to make the most sense to be in the same room at the same time.”

How do you work? Do you have to communicate with each other a lot or is it all quite instinctive?

James: “Obviously we’ve been in bands and DJed together for a scary amount of time so that amount of energy you put into a common understanding does count for a lot. There’s a lot that you don’t have to say and a lot of things that are a given and I think it’s definitely very valuable, especially when I spend a lot of time working with lots of different people as well. I often walk into a room and have to make music with people who are pretty much strangers and that really makes me realize how easy it is making music with Jas, because you do have to tread carefully and build a new relationship with someone each time. That being said, Jas is always someone who’s challenged me to do something unexpected.”

Jas: “I think if we’d only made music together eventually it would have become frustrating. But because both of us disappear off and do quite different things – for a while I was off DJing and making really nerdy techno and James was working with lots of different bands – when we came back together we challenge and maybe slightly surprise each other, but without falling out because we go back so far. We don’t have to tread carefully, we can just say “right, what about if we do this” and not have to worry that the other is going to take offense about it. It’s not a telepathy but a kind of an understanding of each other – when we come back, it’s not the same old, same old. There’s something new for us to explore.”

Jas, how has your recent diagnosis affected your work?

Jas: “It’s affected my work in that I can’t do much of it at the moment. I’ve been having chemotherapy, so my activity levels are really low. I’m not moaning because I’ve not had any of the horror story things that you hear about chemo – I’ve just got cotton wool brain and I’m feeling really tired, and generally just even a tiny amount of activity gets me knackered. But this whole thing has made me think a lot about how I would go forwards in terms of music and it made me wonder if I need to change my priorities. I thought maybe I would just take the bits I really like out of what I was doing and that that would fit into the week. And then I thought about what I was doing, and I actually really like all of it.”

“It’s frustrating because it wasn’t a solution but also it’s kind of heartening, because it made me realize that I’m already pretty idealistic about music. I don’t have anyone in the studio that I don’t like and I don’t really work on any projects that I don’t like and I appreciate that’s something that I’m very lucky to be able to do. And if I can keep doing that then that would do, just working on the things that things I care about. So it’s not really changed anything – but it’s certainly brought it into focus.”

Scott Wilson is FACT’s tech editor. Find him on Twitter

All photography by Pete Everett

Watch next: Emma-Jean Thackray – Against The Clock