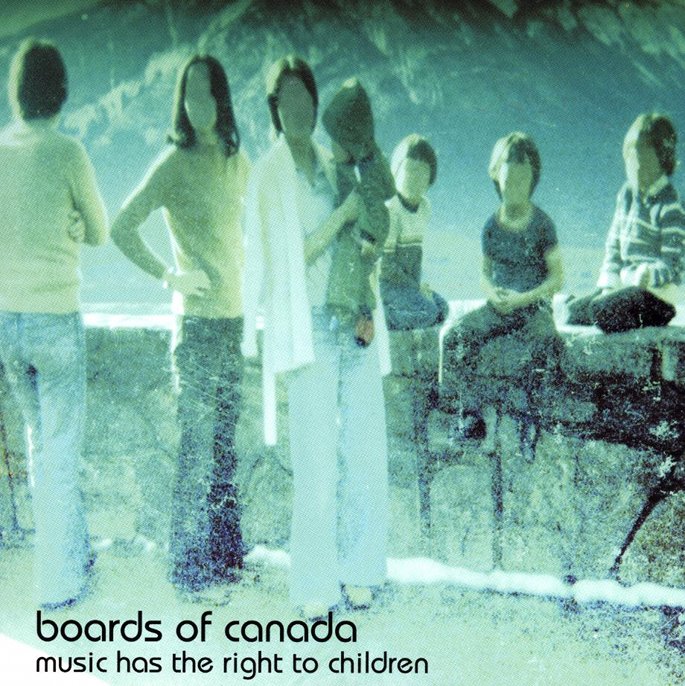

Few albums are treated with the cultish reverence of Music Has The Right To Children, which turned 15 this April.

Whichever way you look at it, in the decade and a half since its release, Boards Of Canada’s Warp debut has acquired a mythical prestige that transcends both the Sandison brothers’ original ambitions and the music’s own guileless outlook. Perhaps surprisingly for a record so fanatically adored, not even all the material on Music Has The Right To Children was new: ‘Turquoise Hexagon Sun’ had appeared on Hi Scores in 1996 and on the collection Boc Maxima (released on the pair’s Music70 label), which also included ‘One Very Important Thought’, ‘Roygbiv’ and ‘Wildlife Analysis’. But where that record pulled together Boards Of Canada ephemera into a musically pleasing if conceptually underwhelming whole, Music Has The Right To Children was a unified work proper.

Despite its name, Music… is about as grown-up as records get: an adult meditation on childhood, concerned with play, naïveté and nostalgia, all tinted with rosy pastoralism. But it’s also devilishly subtle, intricate and emotionally mature. That’s surprisingly rare in electronic music, most of which is concerned with the physicality of dance, intellectual weight, or the evocation of atmosphere rather than a holistic experience. By introducing themes of suppression, solitude and grief into Music…’s evocations of childhood, Boards of Canada created a record that was pretty but seldom precious, more faithful to experience than kitsch idealism. This ambiguity has endeared Music Has The Right To Children to its hordes of fans over time: as its listeners grew ever further away from the childhood it evoked, the album, bizarrely, became more relevant.

Track names like ‘Pete Standing Alone’ and ‘Happy Cycling’ contain obvious markers of the childhood conceit, but so do titles more centred on learning, like ‘Roygbiv’ (the acronym for the colours of the rainbow) and ‘Triangles and Rhombuses’. Tracks like these illuminate what, if any one thing, Music… is ‘about’: the fragility of the zone between innocence and experience, instinct and learning, blissful ignorance and the weight of knowledge. But it’s Music Has The Right To Children’s allusiveness – its palette of submerged samples that hint at unspoken memories rather than spelling them out – that’s proven to be its most enduring quality.

Music Has The Right To Children’s formula is essentially very simple: yearning melodies and a subtle attention to texture and timbre. Those melodies still capable of bringing a lump to the throat, from the piano in ‘Olson’ to the synth passage in ‘Bocuma’; these moments, informed by the TV and film tunes that shaped the Sandison brothers’ youth, are pregnant with yearning. Similarly, that rich textural detail lends itself wonderfully to intimate headphone listening – take the bubbling, liquid synth line of ‘Turqoiuse Hexagon Sun’, set against the faintest breath of tape hiss, or the pastoral twinkle of bird sounds in ‘Rue The Whirl’, the result of days spent editing and processing field recordings of birds outside the brothers’ studio. The instrumental and concrète samples are artificially antiqued, a dusty golden patina retrospectively applied, rendering new recordings at once aged and ageless.

Then there are the vocal samples of children: children counting, reading, laughing, chattering. There’s even a Sesame Street sample of a child learning to write the words “I… love… you” in ‘Color Of The Fire’. Similarly childlike is the way the brothers Sandison coat the tracks in snippets and samples, paying little attention to the confines of the grid; the effect is a little like an outline loosely coloured in with delighted abandon, pigments allowed to bleed and mingle. That these samples and loops dissipate as quickly as vapour only adds to the atmosphere of something intangible, gone forever.

It’s tempting to paint Music Has The Right To Children as a dazzling innovation, but it’s simply not true. Rarefied status notwithstanding, Music Has the Right To Children had plenty of precedents within and outside Boards Of Canada’s pre-1998 catalogue. Most obvious are the debts to other Warp artists Aphex Twin, Brian Eno, Autechre and LFO, as well as dream-pop duo Cocteau Twins and Arthur Russell. Its particular flavour of trip-hop by the late 90s was already well established in the UK, even tired, while IDM was already on its way to effecting its own obsolescence. But just as Music Has The Right To Children specifically embodies childhood in order to examine it from an outsider’s perspective, its own lack of timelessness reinforces rather than detracts from its spirit of nostalgia. Familiarity rather than daring, then, is Boards of Canada’s weapon of choice; by tweaking a blueprint slightly, Boards of Canada – not unlike Burial ten years down the line – refined a specific sound and made it entirely their own. The lack of deviation in style is part of their style (Geogaddi – slightly darker, more refined, and more varied in mood and colour – is in many respects Music Has The Right To Children’s superior).

Still, for all the uniformity of the Boards of Canada back catalogue, it’s hard to overestimate Music Has The Right To Children’s influence, the gauzy ripples of its nostalgic haze still palpable in a good deal of today’s music, from the stoned melancholic atmospheres of cloud rap to the polychromatic beat music of Lone, Gold Panda and Lapalux. That’s to say nothing of so many electronic artists wedded to emotional melody rather than sophisticated drum programming: Four Tet, Ulrich Schnauss and Bibio spring immediately to mind, all of whom, like Boards of Canada themselves, often veer dangerously close to twee saccharinity. Nor are subtler experimental artists immune to Boards Of Canada’s poignant fuzz. It’s hard to imagine all of Leyland Kirby’s The Caretaker’s albums or Tim Hecker’s Ravedeath, 1972 in a world where music doesn’t have the right to children.

Perhaps all those artists influenced by Boards Of Canada are, in their own way, trying to fill the voids between albums: three LPs in fifteen years is hardly the stuff of unbridled creativity, and since Trans Canada Highway in 2006, the only Boards Of Canada transmission has been silence. That is, until Record Store Day 2013, which saw the advent of the first clues pointing to a new album. The Tomorrow’s Harvest campaign, with its hyper-nerdy numerological clues and 12-second 12-inches, has felt like a choose-your-own-adventure with a depressing twist – someone else is making the choices, they’re uniformly disappointing, and the conclusion’s foregone anyway. Strangely, the campaign’s convolution illuminates how though many records may sound like Music…, none, not even a new Boards Of Canada album, can ever repeat its wide-eyed wonder. It’s not a little sad that the mysteriousness that made Boards of Canada so many people’s favourite band has become a viral ploy fifteen years after the fact, but the musical landscape is a very different place now. In that sense, Music Has The Right To Children isn’t just a classic album or many people’s personal favourite. It’s an artifact in its own lifetime, a present-day relic that recalls an innocent time in more ways than one.