“Don’t worry, he’ll call you.”

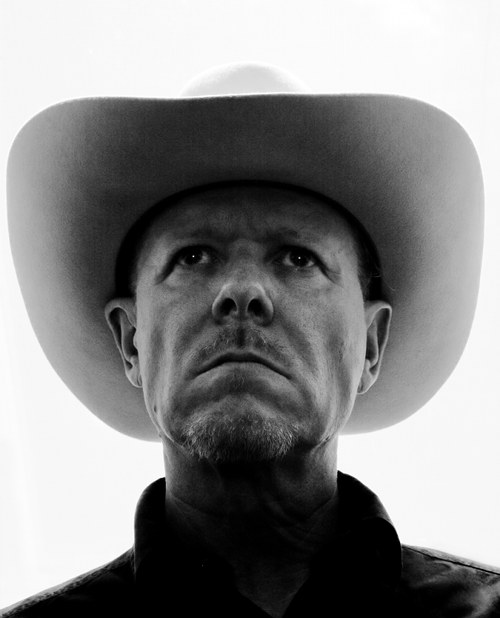

When you’ve been doing journalism as a dayjob for almost five years, interviewing your heroes doesn’t really intimidate you anymore. When one of your musical heroes is Michael Gira, however, things are different. Leader of Swans, the greatest band ever produced by the New York underground, Gira has been making brilliant, uncompromising music for 30 years. Live, even solo, playing acoustically, he is a fucking force of nature. And famously, he doesn’t suffer fools gladly.

A friend of mine was supposed to interview Gira two years ago. He called late, and was told to reschedule. The rescheduled interview never happened. So when I realise that despite having questions prepared, and having immersed myself in Swans’ excellent new album The Seer, I don’t actually have Gira’s phone number or Skype username for the call I’m supposed to make in 15 minutes, I start to sweat. I email his PR. Don’t worry, she says, he’ll call you. The fear factor sky-rockets.

As it happens, Michael Gira wasn’t that scary. He’s stern, he’s eloquent, and he speaks in the sort of composed, fully-formed sentences – semi-colons and all – that a stammery East Londoner like me could never manage. He probably speaks like this because, although he talks about Swans – reformed in 2010, after almost 15 years in hibernation – as if it’s an element or force, part primordial, part astral, he’s also got a remarkably clear idea of what it is he wants to do with the project, and why it is that he chose to revive it. At a couple of points, he even laughs.

I was struck by the fact that Swans’ last album, My Father Shall Guide Me Up a Rope to the Sky, was such a powerful, passionate album released at a time where countless other bands from your era were clearly reuniting for a quick buck. When you chose to revive Swans, were you conscious of the context in which you were doing so, and eager to prove that you weren’t part of that?

I was struck by the fact that Swans’ last album, My Father Shall Guide Me Up a Rope to the Sky, was such a powerful, passionate album released at a time where countless other bands from your era were clearly reuniting for a quick buck. When you chose to revive Swans, were you conscious of the context in which you were doing so, and eager to prove that you weren’t part of that?

“I don’t try to prove anything to the press or the public, or anything. It was a personal necessity that I revive Swans, and extend my music. I’d reached an impasse with Angels of Light, and this seemed like the logical thing to do. It’s my life’s work, making music, but I don’t look at this like a career option – it’s something I’m compelled to do, and Swans is the best I can do with music at this particular moment, just as Angels of Light was previously.”

Had Angels of Light reached a logical conclusion to you?

“Yeah, it wasn’t doing it for me, that aesthetic. I wanted to experience those huge sonic environments again, and so it made sense to call it Swans. There are gentle moments on the new album, of course, but it’s more about those overwhelming waves of sound, and that’s what I associate with Swans.”

So you wanted to go back to something more physical?

“I look at it more as transcendent.”

I think I’m right in saying that both My Father and The Seer’s songs started acoustically with you, and then became bigger pieces with other musicians. Obviously the cast of musicians differs between Swans and your solo work, or work with Angels of Light, but if, in both cases, the songs start with you writing alone, how do they differ? Do they come from the same place, or when you sit down to write for Swans, is it coming a different mindset?

“Well actually, with the new album there are four songs that were developed pretty much entirely on tour. We played them in front of audiences in their nascent stages and then they took shape, just as we’re doing on this tour; we’re playing new songs which aren’t quite finished yet and letting them develop. But yeah, I come up with the basic chords or rhythmic idea and bring them to the band – in that instance – and we treat it as a sonic event, or a groove, I suppose, naturally with my direction but with the band having a lot of input. That’s one way of making songs, building them up sonically. There are other songs on the album that are written on acoustic guitar, then played with a drummer and built up in the studio. I can write songs any way I want [laughs], and so I do.”

I haven’t seen you live in several years, but you were playing some two, three hour shows last year. Is that how tracks like [the 30-minute] ‘The Seer’ grew?

“Yeah. Our set right now begins at two hours [in length], but I don’t know how they’re going to end up. We have three new songs we’re playing live, a couple which don’t really have words, I’m just singing whatever comes to mind and then I’ll grab words. But it’s enthralling, the whole prospect – it’s like I’ve been reborn.”

Has it changed your perspective on Swans? There was that line, in the press release sent out for Our Father, about you thinking “maybe Swans wasn’t so bad after all”. I’m sure that was a little tongue in cheek, but has reviving the project changed the way you view its past?

“Well when I first stopped Swans, in the ’90s, it was a 300-pound ape on my back, chewing my head, it was an onus – it had become an onus. So in my mind, I had made it into a very negative thing. But of course, when I looked back at it, I saw the good things in it.”

Use your keyboard’s arrow keys or hit the prev / next arrows on your screen to turn pages (page 1/2)

Did you miss Swans in the years that it was dormant?

“No. Towards the end I started to missed the elation, the joy of being inside the swirl, this maelstrom of sound which we’re experiencing again. And aside from the hearing damage, I find it very elating. Very inspirational.”

Is it an addictive process?

“Addictive? Yeah, I guess so. It’s like a little bit of ecstasy every day, while preparing a show. It’s a quasi-religious experience.”

You describe The Seer as thirty years in the making. Could you expand on that a little? And what particular experiences in those three decades, from both your music with Swans, Angels of Light etc, and you as a person have particularly shaped it?

“Well, I think you can hear various ways that I’ve made sound – if people know the records – in all of this. There’s… what’s the word, not textures, that’s too benign… there’s lots of different thrusts. Say on the song ‘The Seer’, which is 30 minutes long, it’s very physical at times, but at others it’s like shooting up to the sky. Some of it reminds me of early Swans, but then there’s gentle moments that remind me of Angels of Light. Then, at it’s more cinematic moments, I guess that’s Body Lovers or Soundtracks for the Blind era Swans. It’s really just that whatever vocabulary I have, I’ve utilised. I was very aware that this was potentially a really great record, and I didn’t let that go until, as a producer, I’d done the best that I could do.”

Former Swans vocalist Jane Jarboe appears on The Seer. Under what circumstances did she return to the Swans fold?

“We saw each other in Atlanta when we were on tour recently. As I was making the record I thought that I wanted some female drone vocals, but I wanted them to be earthy, so naturally I thought of her vocal range. I asked her to contribute, and she did it, there was nothing monumental in the process. It was great to have her involved in some way, and maybe I’ll involve her more in projects in the future. That’s about it, really. She did a great job.”

You offset a lot the album’s costs through fan-funding. Obviously over the last decade or so you’ve released quite a lot of small-run products, and presumably sold a significant number direct and built up a relationship with your fans in the process, but was it difficult being reliant on fans to fund the record above and beyond simply buying it?

“It’s all difficult these days, and you have to do whatever you can to survive. We’re lucky enough to have a fair sized fan base that wants to support us and wants to see us continue, so they actually buy things. You do whatever you can, as a musician, to survive. I have no other skills or prospects. It’s a lot of work doing the hand-made things, but I have no other skills. I don’t know what I’d do otherwise.”

Would you ever go back to a bigger label?

“I don’t see any point. They don’t sell records either. The autonomy that I’ve achieved over the last 15, 20 years is something I treasure, and nobody’s ever going to tell me what to do.”

You describe The Seer as unfinished, in the sense that the songs will eventually evolve in the live setting. Is writing with that attitude new to you, or did you always do it?

“It’s been a revelation. Of course I did everything possible to make a perfect record, but in the end you’ve got to let go. By the time I’m done with it, I’ve listened to it so much that it’s just dead matter. Maybe in 10 years I’ll listen to it again, but I’m more interested in what happens now, which is why when we play live, and we play three or four songs from The Seer, they’re morphing into something else, which is how I prefer it. I just want things to remain vital and urgent and necessary, I don’t ever want us to be a band up there just aping their record our trying to sound just like their record. I find that tedious.”