At first glance, Lee Gamble‘s feet are are firmly fixed in the more academic fringes of contemporary electronic music.

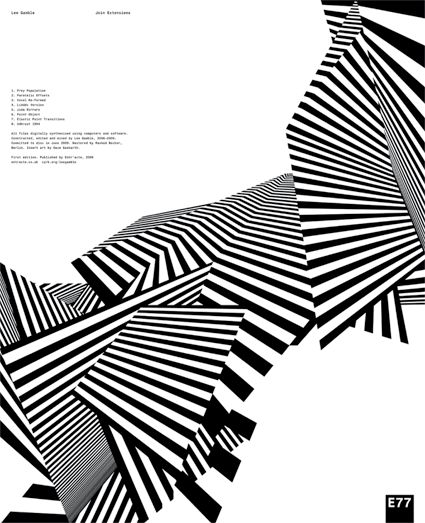

In his role as a key member of the speccy Cyrk collective, Gamble has curated or contributed to work by William Bennett, Russell Haswell, EVOL and NHK; his sonic collaborators (digital composer John Wall, artist Yutaka Makino) are from similarly rarified environments, and austere experimental stable entr’acte have handled his solo releases. 2006’s 3″ CD 80mm O!I!O let complex digital processes run wild, with chaotic and spastic results. 2009’s oblique Join Extensions, meanwhile, was a tribute to “perpetual configuration, disfiguration and reconfiguration” – five words which accurately sum up whether the record will be for you or not.

Gamble’s roots, however, lie in much grubbier soils. The Birmingham native came up DJing on pirate radio stations, and spent his formative years in the mid-1990s as an active participant in the jungle scene. His recorded work is all about process, sonic disfigurement and deliberate abstraction – but there’s raver’s blood in those veins.

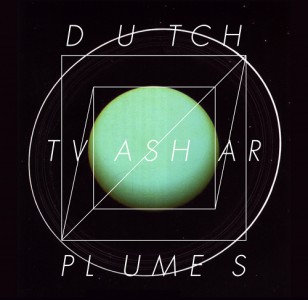

Two major releases on Bill Kouligas’ PAN label see Gamble pursuing two different sorts of muse. Forthcoming ten-track LP Dutch Tvashtar Plumes sees Gamble produce a sort of twilight computer music: a gossamer-thin collection of ambient and techno, it’s a comparatively accessible step on from the sonic essays found on his previous solo discs.

Diversions 1994-1996, meanwhile, is a breathtaking 25 minute composition for 12″ vinyl, cobbled together entirely from samples of jungle mixtapes from the mid-1990s. Unlike, say, the ludic trance recontextualisation of Lorenzo Senni’s recent Quantum Jelly, Gamble’s exercise in “cued recall” is a genuinely uncanny offering. Familiar elements – snare rattles, salacious vocals, horns – are left to degrade or hang in the ether; the effect is wonderfully elegiac.

FACT checked in with Gamble to discuss post-rave hallucinations, jungle’s eerie blind spots, and the “thief music” clogging up the Top 40.

PAN has been a real hive of innovative activity this year. What attracted you to the label for these releases?

PAN has been a real hive of innovative activity this year. What attracted you to the label for these releases?

“I’ve known Bill [Kouligas, PAN founder] for years. He asked me to make a record for PAN about many years ago. He heard some of my new material and was also keen on releasing it. A version of Diversions 1994-1996 was originally made for radio; Bill and I spoke after he heard it and thought it would make a nice EP release before the album (which I had already finished). I wasn’t totally happy with it, so I reworked it further for a couple of months to turn it into something resembling a proper release. PAN seems a good place for me to release the kind of material I’m making now too.”

With the exception of the disc’s closing moments, your jungle source material on Diversions 1994-96 is largely processed and warped beyond recognition. Do you feel that any of the character of jungle inheres in the music? Or is the finish product wholly severed from its provenance?

“The music during that period shape-shifted weekly, so the character itself was in flux. The immediacy of jungle was of course in the breaks, bass and samples, but the scene as a whole had a vibe I was hooked on. When I was involved in it in Birmingham, I was a teenager. At that age you get kind of obsessed, and it becomes more than just a music genre. Also, I was mostly too young to legally get into the clubs anyhow, so lots of my experience with it was detached and cerebral.

“At the time I worked in a steel factory in Digbeth (which is on the outskirts of the city centre). At work I used to listen to mixtapes on my headphones and stuff, and use practically all my wages on a Friday and go straight to Don Christies (which was a reggae record shop with a jungle/d&b counter in the basement). I got to know DJs and MCs in there who became friends. We would hang out and eventually DJ at raves together, there was also a pirate radio we used to play on. So the whole scene encompassed so much for me. The places you used to hang about, the people involved, y’know? It really was the first music I could call my own, something I’d found, rather than been fed.

“I hope it doesn’t appear completely severed. It feels ‘in there’ to me. Jungle had this dystopia/euphoria dualism, which I think is retained in Diversions. I never had any intention of remaking the music intrinsically, like some amen break tear-up revision. That was never in my mind. I wanted to take the sound and make something new. Something that felt respectful. The main focus was on the bits in between the breaks really, like the little breakdowns, I wanted to open them up, go in with a microscope and expose something in those parts that may have been overlooked at the time. They were often the strangest moments in clubs, when everyone is waiting. You know, just this heavy bass, hung chord and a disembodied voice or whatever…”

In the last year, [Mark Leckey’s] Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore has been issued on vinyl, and Channel 4 has taken great pains to celebrate the supposed “anniversary” of acid house. How do you feel about the way rave music is being remembered, decades after the fact?

In the last year, [Mark Leckey’s] Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore has been issued on vinyl, and Channel 4 has taken great pains to celebrate the supposed “anniversary” of acid house. How do you feel about the way rave music is being remembered, decades after the fact?

“I had never seen or heard of this work [Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore]. It was only when me and my mate were working on a video for Diversions and he mentioned it and showed it to me. I removed myself completely from the jungle scene around 1998, I started to listen to and study extensively about more avant-garde composition. So, I guess it slipped through my radar. I didn’t know it had been issued on vinyl either. I still haven’t heard it!

“Lots of cultural stuff seems to have this ’20 year’ cycle, so it’s kind of inevitable that this would happen. That 20-year timeframe is changing now though, I guess. The musical archive that YouTube has turned out to be kind of compresses time in this strange way, and this easily accessible digitisation of history has had a huge effect. You can basically do a virtual crate dig of the last 25 years of dance music history over a weekend. I mean, I use it like that myself; it’s an amazing resource.

“There was an almost immediate nostalgia for ‘rave’ in the UK. Eventually, there was a split in the music and in the clubs, where ‘rave’ and ‘hardcore/happy hardcore’ went one way and jungle/drum and bass went another, and it really wasn’t long after this that you had ‘back to 92’ clubs and stuff. So it’s not a new thing, but sure, with decades passing it’s different now. I don’t know really, I don’t see why any music should be seen as ‘sacred’ or ‘untouchable’. Everything is out there now, so people have just got to work out how to make sense of it all. There’s some amazing stuff being made, which seems creatively driven by this situation.

“On the flip side of that, there does seem to be a resistance in electronic music at the moment to look forward, in the way that, for example, each new Autechre album tears a hole in what a rhythm can consist of, bpm wise, polyrhthmically, melodically, the sound palette, etc. Nostalgia does seems to dominate but of course there are exceptions. I can honestly only think that the way the world is at the moment politically, socially, geologically, that this is indicative of a more broader social mindset. The past is way safer y’know.”

Moving onto Dutch Tvashar Plumes: does the record have similar compositional restrictions to Diversions 1994-1996?

Moving onto Dutch Tvashar Plumes: does the record have similar compositional restrictions to Diversions 1994-1996?

“No, not at all. All of the sounds on Diversions are sourced from my tape collection. Nothing else was added. With Tvashar I was keen to take away all of the rules I had put on myself with my earlier computer music stuff and just make something. I had to learn how to work with new equipment, software, etc. It’s odd really, because I’d used these strange often awkward academic softwares and I hadn’t really used any ‘off the shelf’ software for many years. So it was like learning in reverse or something. I was teaching myself and building up my studio whilst making it.

“There was a point after a couple of years noodling where I was like ‘ok, so this is what I’m making’; I started to think about it in terms of titles and stuff. I think when you’re learning how to do something, your lack of mastery over the software or hardware can lead you to some interesting spaces. I really can’t make music by numbers anyhow. Like, ‘this is how to make a house record stages 1 – 10’. Some of those skills are important but I guess I have a more playful approach, which probably comes from my background making more experimental stuff. In his writings the inventor of musique concrète, Pierre Schaeffer, emphasized the importance of ‘play’ (jeu) in the creation of music. Just see what the sounds imply to you.

“Saying that, I did always have a loose idea my head of how I wanted it to sound and feel. Something like a copy of a record that may have already existed but that you hadn’t heard yet. You know sometimes when you go to bed in the morning after a rave and you can ‘hear’ music in your head? Most of the time it’s a fragment or a rhythm or a phrase. Often you aren’t sure whether you’re making it up, or whether you’re replaying something from the night. Neurologically, these are called ‘release hallucinations’. When your brain is starved of a source of stimulation it has become accustomed to, it can start introducing memories (in this case musical ones). The brain wants to stay active and when it’s starved of this input it can create a hallucination. I was interested in taking this idea as a way of producing an album. Like making a Xerox copy of a record, something battered, making something that sounds like something but isn’t actually the thing itself, if you know what I mean!?

“Saying that, I did always have a loose idea my head of how I wanted it to sound and feel. Something like a copy of a record that may have already existed but that you hadn’t heard yet. You know sometimes when you go to bed in the morning after a rave and you can ‘hear’ music in your head? Most of the time it’s a fragment or a rhythm or a phrase. Often you aren’t sure whether you’re making it up, or whether you’re replaying something from the night. Neurologically, these are called ‘release hallucinations’. When your brain is starved of a source of stimulation it has become accustomed to, it can start introducing memories (in this case musical ones). The brain wants to stay active and when it’s starved of this input it can create a hallucination. I was interested in taking this idea as a way of producing an album. Like making a Xerox copy of a record, something battered, making something that sounds like something but isn’t actually the thing itself, if you know what I mean!?

“So, not only aesthetically but also technically I had to work out ways to kind of ‘age’ the sounds without reverting to just sticking a tape-emulation plug-in on everything. Over the years I’ve built up a large library of sounds, stuff from my experiments with different digital synthesis/DSP methods and tape stuff too. With Tvashar I wanted to put these sounds into a new structure, more melodic, more functional, less abrasive than before. I wanted to make something that people will want to put on at home and listen to for a while, not just a week or so, who knows? You have to at least try, right!?”

Use arrow keys to turn pages (page 1/2)

Compared to 80mm O!I!O – and Join Extensions too, I suppose – Dutch Tvashar Plumes strikes me as a gentler, more taciturn record. How has that change come about?

“As I said, the change was mainly one of self-imposed rules. With those previous records I was completely strict with myself in regards to, for instance, sampling. 80mm O!I!O and Join Extensions are made from experiments with more obtuse digital synthesis and DSP methods. I would in no way allow myself to sample anything, they were made on two or three computers, no soft synths, no external controllers, very few plug-ins, etc. It made sense to be totally strict with myself as I was interested in exploring what the computer could do, in a way, ‘in itself’. They were explorations of the machine I guess, what I could do with it, how far I could push it.

“I worked out ways of crashing software and recording the output and stuff like that, also setting processes off overnight and editing down the results (which were often shit). Nowadays there is so much software and the computers are becoming so powerful, that the limits are endless. It seems crazy to go to the levels of processing I did to create some of the sounds on those records, when most people will just think you are just fucking around with a midi-controller and a Max patch. I really don’t enjoy writing and learning programming languages much either, so I was getting frustrated at how far I could take it. My split cassette from 2010 with the artist Yutaka Makino still uses these techniques, but is me heading away from it too.

“With this new approach, I can allow far more of my interests appear in the music. I still use some of the earlier approaches to create sound and I’m still not a huge sampler right now, I like making sounds. But the results are aimed in a different direction. I definitely wouldn’t say it’s more taciturn though, it feels like it has a lot more to say than the earlier computer-music releases. Hopefully there are more references for the listener to chew on. The earlier records were far more one-dimensional, and that was the point.”

Can you tell us about your recent work with Bryan Lewis Saunders?

“Bryan got in touch with me and asked me if I would like to work on one of his ‘streams of unconsciousness’ recordings. These are recordings of him sleep-talking into a cassette recorder. I decided to work on re-synthesising parts of the text in software developed for Articulatory Speech Synthesis. My offering is part eight of a twelve cassette box set, which forms a kind of audiobook, 24 chapters in all. He asked a different artist to collaborate with him on each part. It’s interesting to work with people like this – artists as opposed musicians. His work is mental.”

Where does live performance fit in with your work? Does it resemble your compositional practice in the studio?

Where does live performance fit in with your work? Does it resemble your compositional practice in the studio?

“Absolutely not, no. The music takes me ages to make; there is no way of me creating it on the fly.”

Thinking about the way in which your recent work muffles or obscures the tropes of dance music, I wondered if you’ve paid much heed to the EDM phenomenon in the States – which seems to be preoccupied with making those same tropes more gaudy and lurid than ever before. Dutch Tvashar Plumes seems like the absolute inverse of that.

“Dutch Tvashar Plumes may be an inverse of it but it’s nothing to do with what I do, EDM is a pure business operation it seems. I’m aware of it, but can’t say I have paid much attention to it. It’s painful to listen to. It’s empty of any style, but I guess we can use it as an antithesis. Theo Burt’s (The Automatics Group) recent release on Entr’acte is an interesting take on it, for instance.

“It does seem criminal that America has brought us such amazing music over the years, then it’s shipped back, and dumbed down like this. Dance music is in a constant flux. That’s its nature; it’s a global phenomenon, which has no actual geographical base. It retains a certain functionality for it to work, but in a sense, it’s still experimental. So these, base level, purely moneymaking versions, will crop up from time to time. It’s big business. People there seem to be having a good time, so that’s cool I guess!

“When you have to please 20,000 people in a rave, I think there’s an inevitability that the music will be dragged to its most basic level, it’s TV advertising music. It’s directed at you. There are huge amounts of money being made too. Rave culture in the UK died when raves became these monolithic festivals. It becomes hysterical, adults with dummies in their mouths, demigod worshipping. The DJs are like children’s TV presenters. It’s thief music in the most boring way.”