Illmatic has always been more than just a record.

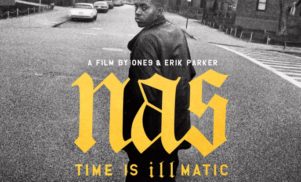

On its release in 1994, it was a ten track LP that sought little more than to distil the street level observations of youthful Queens native Nasir Jones. But in just thirty-nine minutes and fifty-one seconds, it managed to redefined a genre; ushering in the second epoch of rap, launching the career of a global icon and crafting a legacy that endures today. So with the 20th anniversary upon us – and Illmatic XX a contender for reissue of the year – it’s an ideal moment to release a new documentary on the album, Nas: Time Is Ilmatic. In gestation for a decade, the film not only tells the story of the album, but of life in New York in the late ’80s/early ’90s and how potent forces of a city in flux influenced the record. With this in mind, we spoke to the film’s director, multi-media artist and first time documentarian One9, about working with Nas, the virtue of patience and ensuring his film has a life beyond the cinema.

So you began making Time Is Illmatic just before the 10th anniversary, it’s now the 20th…what took so long?

I relocated to New York in 2000 I connected with a lot of artists. Eric Parker (the film’s writer and co-producer) and I had met through work and stayed in touch. When he called me in 2004 he was a music editor at Vibe and said he was doing a print piece on the ten year anniversary of Illmatic. He wanted to know if I would be interested in shooting some video for a DVD because he knew I had a camera. It was an interesting idea to me, so I thought, why not? We went to Nas’ father’s house and it started there. Our interview with Olu Dara really shaped what was to become the finished film. So much information came out of that, and we realised we had a much bigger story; one that crossed generations and dealt with the wider issues that surrounded the Jones family. But when we started, we both had full time jobs and were funding it out of our own pockets. Eric spearheaded it and kept the project moving forward. So after our interview with Olu, we went on to speak with Large Professor, DJ Premier, L.E.S, Pete Rock and Q-Tip. Just fitting in interviews whenever these guys had the time, with no set schedule in mind. Back then we really thought we could finish the film in a year and get it out for the 10 year anniversary – which looking back, was never going to be possible.

The film definitely leans towards more of a social document rather than a conventional music documentary. Did you always have a clear idea that this was the way to tell the story of Illmatic?

Yeah, we didn’t want to make a behind the scenes music documentary that just focused on the linear structure of the music. It was always more important for us to tell a proper story, so we decided to create our narrative based around the album’s song titles. They opened up a bigger framework for us, one that went beyond the beats and into the social issues. We started thinking about ‘New York State of Mind’ and how it related to the history of the Queensbridge and the development of the housing projects. While for us, ‘Life’s A Bitch’ applied to the dissolution of the family home and ‘One Love’ to the problems of the prison system. We wanted to look beyond the songs at the ideas that inspired the music.

And yet he was so young. Do you think it’s easy to forget how old Nas was when he made that album?

Totally, it’s crazy. He was just eighteen years old and spitting prolific, insightful words. That’s because of the mix of the books he’d read, combined with the extreme conditions that he was facing. So he was forced to become a man early – I mean, there was was no internet at the time, so you were just outside experiencing life. He was living his teenage years but with a man’s soul and those are extremes most teenagers never have to deal with.

When did you first meet Nas?

After we’d shot a few interviews we cut a short trailer together we sent it to Nas’ manager. He asked us to meet and brought Nas with him. At first Nas was very guarded, listening to us, but not giving any confirmation of what he thought. We left that meeting without a firm commitment of his involvement, he just said we should carry on and keep him informed about its development. So we to kept shooting.

So when did it start to feel like the movie was going to get made?

A few years down the line and we updated the trailer and got it into the hands of the people at the Ford Foundation. They offered a research grant so we could get more immersed in the film and flesh out some scenes. It took almost another year, but eventually we cut a couple of scenes together, sent them back for approval and the next thing you know we had a full production grant. That was seven or eight years since our first interview. I don’t know if I would recommend taking this length of time to make a film to someone, but I don’t like to leave things undone, it’s important to finish what you started.

It must take a lot of devotion and patience to make a film over a decade, ultimately what do you put that down to?

Chess. A lot of things I know about art I learnt from chess. One of my first girlfriends showed me how to play and I was addicted – I still play religiously to this day. It’s taught me so much about how to visualise where you want to go and about the virtues of extreme patience. It’s also taught me about how to take risks and how to sacrifice.

So at what point did Nas actually commit to the film?

Once we got the grant we quit four jobs and decided we’d finish the film. So we called up Nas and he said he could give us twenty minutes of his time to look at what we’d got. So he came up to the studio and we showed him old footage of him walking through Queensbridge that he has never seen, then we showed him some photographs that we’d found of his friends from back in the day and he was blown away. He went on to tell us incredible stories about these people and their lives and those 20 minutes turned into an hour, and then that became two hours and he just didn’t want to leave. Then he called his brother into the studio and they both ended up spending the whole day with us, watching footage, telling jokes, discussing the past. After that he told his manager to clear out his schedule because he wanted to help us finish the film. He realised that this story was bigger than all of us – it’s the kind of story that is much needed in hip hop, one that can move the culture forward.

He’s notoriously reserved in most interviews. Did you find him easy to work with?

Yeah, he’s a true artist. He expresses his deepest feelings in his music – he’s very honest in that space – but being able to talk to someone with that same honesty in an interview is a different thing entirely. But once we got to know him, it felt like you were talking to an old friend and it was very revealing.

You manage to dig up some rather obscure people from Nas’ past. How important for you was it to explore the lives of these peripheral characters from Nas’ life?

Part of what we wanted to do was find people who’d had direct contact with Nas while he was growing up. In particular, we had a group photo and were trying to find everyone on in that shot, and it was through conversations with Nas’ brother Jungle that we learnt what happened to everyone. He had a heartbreaking story about almost everyone in that photo, so it was important that our film told that story. Y’know? Giving a voice to the voiceless. The people who are no longer here, or locked up or missing. Those are the people that created the Illmatic experience, they’re the people Nas writes about and are part of the stories that make up that album.

Nas’ brother – Jungle – is at the centre of the film’s toughest scene, in which he vividly recounts the murder of his friend Ill Will. Was that hard for him to revisit?

When Jungle walked us through that moment it really crystallised something. You can see the impact of it it in his eyes. He felt it at his core because Ill Will was shot right in front of him. He wasn’t just a friend, he was someone he and Nas had looked up too, a person who shaped the course of their young lives. And much later, after we’d finished shooting, Jungle came up to us and said, “I needed this, it was therapeutic for me to tell these stories.”

And why is it important for you to capture stories like Jungle’s on film?

Things like this happen in every community across the country…across the world. Kids are getting caught up in trauma and we can never tell how it’ll affect them. Nas used music as a conduit to take him into a different place, but most people don’t have that gift. How many people are there out in the world like Jungle? Those who internalise the trauma and express it in negative ways? We wanted to look at those issues, because even 20 years later after Illmatic came out they’re still important.

Queensbridge feels like an omnipresent a character in the film, what is the neighbourhood like?

It’s a dark and stark place, home to the one of the largest housing projects in the US. I mean, it’s huge, and full of so many lives. Those tall buildings obscure you from seeing a lot of the sun, but there are places where you can look out at the whole New York skyline and in a way, I think that gives people hope. Hope that they can get out of that place and into something bigger.

After a decade of filming you must’ve have had to discard so much footage. Was it hard to know what to leave out?

Yeah, it’s always hard, but it’s about leaving things in that resonate, so you create a powerful and concise piece of art. I mean, we have over fifty hours of footage that didn’t make the film. But that won’t go unused – we’ve created a bonus DVD section that has Nas going through each track in his own words and we’ve had the rest of the footage and interview transcripts archived, so that anyone can go and watch them – so much hopefully we’ve left great source of information.

I’ve been reading a lot about the film being connected to educational curriculum. Can you explain how that came about?

Our associate producer is developing an educational curriculum that will see the film enter the school system. A guide book will be produced and clips will be available to download so that people the high school system and colleges can use them. In addition to that, myself and Eric will be teaching a course at NYU about the making of Illmatic, showing how you take a project like this from zero – with experience or plans – to the screen. There’s going to be many facets to the education side of things that we’ll be rolling out over the next few months, hopefully it’ll give the film a life beyond just cinema and cable.

And you opened the Tribeca film festival…how did that feel for your first film?

I’d never focused on becoming a filmmaker or had any formal training at film school or art school. So I’d never even been to a film festival, so when Tribeca told us there was a possibility we could open, it was crazy. When we heard, we sent a message to Nas and he was like, “If they open the festival with the film I’ll perform the whole album.” I couldn’t believe it. I mean, seeing the credits roll and then you hear a piano intro to ‘NY State Of Mind’, you look up and it’s Alicia Keys playing it….it’s hard to put into words, but our movie opening and Nas performing the album on the same night was just amazing.

It feels like themes that you’re talking are affecting people as much today as they were twenty years ago. Do you think that is why Illmatic has stood the test of time; because it deals with issues that refuse to go away?

Illmatic stands the test of time because Nas was honest about his life. He took you to the darkest, deepest depths of hell and walked you out; showing you horrors, but gave you glimmers of light too. Personally, I compare it to Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, which also reflected societal ills but uplifted your spirit. And that’s very rare in music.