The return of Chicago’s Dance Mania has been one of music’s feel-good stories as of late.

The pioneering label, responsible for countless records, careers, and the entire ghetto house sound, relaunched last year, with founder Ray Barney and veteran DJ/producer Victor Parris Mitchell at the helm. Strut Records recently released an excellent two-disc retrospective Dance Mania: Hardcore Traxx, Dance Mania Records 1986 – 1997 (which lined up nicely with our Essential picks, we might add), and interest in the label might be higher than it was during its mid-90s heyday.

We asked Ray Barney, Parris Mitchell, DJ Deeon, and Jammin Gerald to look back at those halcyon times for the definitive oral history of Dance Mania. Then, we handed the mic to Dance Mania devotees Bok Bok, Nina Kraviz, Brenmar, Chrissy Murderbot and French Fries to hear what Dance Mania means to them.

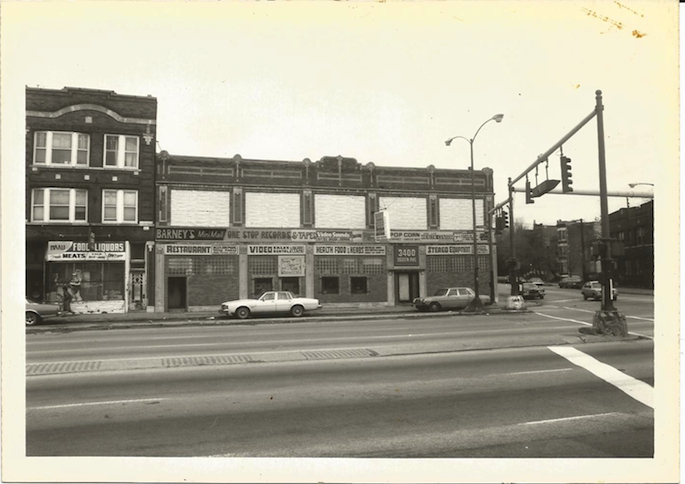

Barney’s Records

Setting the scene

Ray Barney: My dad had been in the music business since before I was born, like the early 50s. We had a distribution company called Barney’s Records that distributed music locally, regionally, nationwide. I grew up in the record business. That was all I knew. I worked in record stores as a kid, and when I went away to college, I would come back on breaks and work with my dad at the distribution company and a couple retail stores. When I got out of school, I took over the business.

Victor Parris Mitchell: I went to music schools around Chicago. I started out as a guitarist in a few bands. In about 1986, my bandmate Kevin Irving was doing stuff with Trax as Jacking House, and he was the one who suggested I do some house music. I tried my hand at it, but it wasn’t going the way I wanted it to, so I stopped for about a year until Vince Lawrence introduced me to Ray.

DJ Deeon: I grew up in the housing projects on the South Side. When I heard ‘Numb’ by Kraftwerk, that got me interested in electronic music. Then I discovered the house music mixes on WBMX. I turned a friend onto the music and he bought some turntables, and we worked on mixes. I got infatuated with electronic music; I didn’t like any mainstream music, I just wanted to hear the imports. The music just grew on me.

Jammin Gerald: I grew up on the West Side of the Chi. I started making music at a young age, in my early teens. I was DJing at a few places and the main one was the Factory. I started guest DJing there in 1986 when I was 16 and they liked me so much they brought me on board. Back then, the music was good. Every weekend I would play house, stuff like Marshall Jefferson’s ‘Move Your Body’. I wanted to have some music like what Farley Keith was playing on WBMX back in the day, so I started producing.

Deeon: There was a guy, Tony T, who was DJing disco. He was buying new imports as well, and he had a lot of records. A couple years later he retired — I think he was going to get married or something — and he passed on his records to us. We just started building from there, buying stuff like Massimo Barsotti’s ‘Whole Lotta Love’, Doctor’s Cat’s ‘Feel The Drive’, and Quango Quango’s ‘Love Tempo’. Shortly after that, Jesse Saunders came out with his [On and On] EP, and when I found out he was from Chicago, that started my interest in producing. I had quit school and I was working at a gas station. I bought my own turntables, my own records, a little synth — what I could afford at the time — and I would just make little tracks to acapellas.

“If you got some good music, you’re in, you’re down with us.”

Gerald: I had borrowed a Boss DR-110 drum machine, and I had a little Casio SK-1 keyboard and I started making tracks. There wasn’t any MIDI or anything, I was just doing stuff by hand. I would play those tracks every week at the Factory.

Deeon: I was playing parties in the projects — Wentworth Gardens, Stateway Gardens. Guys would come from the other projects, and I would play over there. I had been playing for 2 or 3 years on the playgrounds when a guy working for Temple wanted me to DJ. It was a pretty big underground party scene, and I DJed there every Friday and Saturday. The house scene was just starting to explode with jack house. We played two rooms, playing a variety of music: gangsta rap, house, reggae, and old classic disco at the end of the night.

Gerald: We were DJing stuff by Tyree, Ron Hardy, Farley, some hip-hop stuff like Fast Eddie, acid, disco — we would play some of everything, but our main things were house tracks and hip-house. DJ Funk would do guest spots: If someone had tracks, I’d let ‘em play. If you got some good music, you’re in, you’re down with us.

Deeon: I was using an 808, a 909, a 303, plus little portable Yamaha keyboards. I was making personalized mixes. I was staying with my sister, and I would come downstairs, where guys were selling drugs, and they would ask me for the music I played at the parties. I would make tapes, but eventually I had to get a deck to dub tapes because the demand was so high. It was getting out of control. I had a stamp made that said “DJ Deeon Works The Box” and I would put that on the label and sell those tapes for like $10 a piece.

It got popular in the neighborhood, and I’d sell them to the Chinese corner store on 47th and Michigan Avenue; I’d sell them wholesale for $5 or $6. I couldn’t keep up with the manufacturing but I tried the best I could. One day I went to a record store and saw a tape by D-Man on a blue cassette — I thought it was the coolest thing I had ever seen. The guy at the store said he was the best seller, but you could tell he had heard our music — he was doing ghetto tracks, minimal stuff.

Gerald: We would sell the mixtapes at record stores, on the street. It got so big, that’s where Ray came in.

Barney’s Records

The beginning of Dance Mania

Ray: We serviced a lot of DJs who would come over looking for house music in the mid-’80s, and I would sell a ton of DJ International and Traxx. I befriended Duane Buford, who was working with [Jesse Saunders’ group] Jesse’s Gang, and I told him that I wanted to do a music label and he said he would do the first record for me. From then on, it was all systems go.

I already had a warehouse, I already shipped out records every day… it was not a big leap for me to start a record company. I already had the infrastructure set up to run the business; it was nothing new. I didn’t have to buy more space or computers, hire more people.

Victor: In ‘88, I worked for Ray in the distribution company. I left and went on tour with Club Nouveau and when I came back, I started making more records. In ‘94, I worked in retail for him. My first release with Ray Barney was on his Bright Star Records label, ‘You Can’t Fight My Love’. That actually did pretty good, we got some regular rotation in Detroit and on the East Coast in Washington.

Ray: I’m a product of R&B music, I love R&B music. I had the idea at first to do more songs on Bright Star Records and then do the track-y stuff on Dance Mania, but after 4 or 5 releases, I decided to do it all on Dance Mania. DJ International and Traxx really had the commercial marketplace locked up, so I decided to go with more of the track stuff.

Victor: There was another song before ‘Love Will Find A Way’, and it failed miserably. Until I walked in Ray’s office with ‘Love Will Find A Way’, he was looking at me like I was crazy because the last record [‘I Want Your Love’] just sucked [laughs]. He finally heard that, and was like, ‘Okay, you’re back on point.”

Deeon: Ray started releasing records like Eric Martin’s ‘Hit It From The Back’, which took my original idea and ran with it and was pressed on a record. I called Ray, I said, “you put out a track, this is my concept, the guy took my concept,” and he said I’d have to talk to him about that.

A couple weeks later, Armando — rest in peace — took my track ‘Yo Mouf’, and he sampled it and pressed it as a record. I called Ray again, like “this is getting ridiculous, man.” He was like, “Look man, just bring your stuff down here and I’ll release it.” I gave Ray my first 12” record, Funk City, and it’s been all good since then.

“Man, there was no lack of people wanting to do music with us.”

Gerald: The songs were so hot and in-demand that there was no choice but to put them out. The first EP, with ‘Get The Ho ’94’ and ‘Black Women’, those were the tracks that were hot in the Factory. The sound of the Factory back then was influenced by hip-house and a little Miami stuff. We were sampling a lot of James Brown.

The Factory was a real big thing with the kids, and I wanted to keep that name alive, because the original Factory burnt down in 1993. It was a big part of my life; that’s where everything evolved. After that I worked at Rose, Taste, all nice cool clubs, but the Factory was like Studio 54. It allowed me to be more creative: whatever I brought down to them, they’d let you know if they liked it or not. They’d scream, request it again – if they didn’t know the name, they’d sing it back to me.

Victor: There were always people asking me to give stuff to Ray, but if I heard something that I thought was extra special and really good, I would definitely make sure that Ray heard it, like Waxmaster’s stuff.

Ray: Man, there was no lack of people wanting to do music with us. That was the least of my worries. I mean, Victor and I would be in the office and two to five people a day would bring music. And then some of the main guys doing music with me would bring friends: Deeon brought Slugo and Milton with him, Funk introduced me to Gerald, Victor introduced me to Waxmaster. Guys would come independently, too.

Deeon: I was always making tracks. I just wanted it to be universal, and I’d try to mix up the tracks – a little bit of ghetto, a little bit of techno, something for everybody. If I like it, I’m gonna record it. I figure, you’re gonna buy a 12” for at least one of those tracks. That was the idea I tried to pass on to Milton and Slugo. But Ray told me I could do anything I wanted to do; he let me do like four EPs at a time. We had a pretty good time.

Gerald: I had a lot of chances to put out a lot of stuff, but I was real picky about putting music out, it’s just how I was. Deeon was just throwing stuff out there, every time you turned around he’d have a track out there. But I never looked at it like that, “he got a track out, I’ll put one out.” If I felt good about the tracks, then I’d put it out there.

DJ Funk

Ghetto house and the Dance Mania heyday

Victor: Ray got the “ghetto house” name from Funk.

Ray: The first time I ever saw “ghetto house” on a record was with DJ Funk. He actually named a record that [1994’s Ghetto Trax EP as DJ #1]. By us being a major distributor, we would get orders from a lot of places, and people would call in and say “we need some of the ghetto stuff.”

I wish I could take credit for coining the term, but I don’t think I’m that bright to come up with a whole new genre of music. I welcomed the term, I didn’t run away from the term, and I thought it was pretty descriptive of what we were doing. But we never even referred to our music as “ghetto music,” we were just putting out music. I’m sure back in the ’60s, Smokey Robinson wasn’t putting out music saying “this is the Motown sound,” he was probably just doing music.

Deeon: At first, you couldn’t play ghetto house in the clubs, but the streets requested it. I read an article that called us the “stepchild of house music” – the old school house guys didn’t like it because we were cursing and stuff. But when I went to the record shop, I was looking for something like ‘Work This M.F.’, a sample that would catch somebody’s ear, something explicit or obscene, because they like that stuff. It just took off. You didn’t have to pay anybody to play anything. The street made it what it was. I’m kinda happy about that.

Ray: With house music in general, we were the underdogs. We were doing underground tracks for the neighborhood. We never realized how influential and widespread it would get. As far as house music, it was always Trax and DJ International to me. From the distribution end, I sold a little bit of everything — Trax, DJ International, Dance Mania, major labels — and I didn’t realize the impact of what we were doing was having. I just knew that we weren’t trying to clone what others were doing, we were just doing our little thing. We didn’t know how far-reaching it would be.

Victor: It was wide open. I always say, you kinda felt it in the air that it was something new and special going on. It was like the ’60s had come back around, and everyone was experimenting with new types of musical styles. With the vinyl still selling, it was a really good time for music. Off the cuff of disco, the technology caught up a little bit, when the MIDI came out in ’83 – oh, man — you could actually produce a record [with that].

“With house music in general, we were the underdogs.”

Everything was fresh and new and all the major acts were experimenting with new technology like sequencers and drum machines. We kind of took it and made it real raw. Not just Dance Mania, the whole Chicago scene. Labels were popping up here and there, everybody was pressing up records: Westbrook Records, Rocking House, Armando had his own label. So many different labels doing so many different things. And New York was even better! It was all over the place. It was a great time in the music industry: the whole birth of electronic dance music.

Ray: I thought Dance Mania had a reputation, but I didn’t really know how big it was. I don’t think any of us realized how big it was. Locally, people would buy the new Dance Mania when it came out.

Gerald: Dance Mania was kinda known. DJ International was big at the time, but Dance Mania was kinda big too. I bought stuff like Duane And Co.’s stuff, ‘7 Ways to Jack’, Lil’ Louis’ ‘Video Crash’ from them.

Deeon: When I was growing up, if I went to a record store and saw a record on Streetwise or Nervous Records, I didn’t have to listen to it, I just bought it. And that was the same with Dance Mania, people would just buy it because it had that reputation.

Victor: It seems to me that Dance Mania has a better reputation now than it was then. There are less labels now that stand the test of time, so anything on Dance Mania — no matter how rare it is or how popular it was back then — people seem willing to get their hands on it now. I can think of a couple of records that wouldn’t move back that — a couple of mine in particular! [laughs]

Deeon: If the ladies like it, we gonna love it. That’s why I eventually made stuff like ‘Where The Hoez’ and ‘Let Me Bang’, because that’s why the guys came to the party — they were looking for the girls. The guys would want to hear rap, but I would work in techno, jack house, stuff like Mr. Fingers and Farley, but also Geto Boys, Too Short, and NWA. It all played a big part.

The Dance Mania sound has minimal production, no real effects… it’s just simple, man. It’s just funky. It’s like George Clinton, it’s got funk and that easy-listening vibe. I played some of the old tracks to some kids the other day and they thought it was the greatest thing ever, because that funk is the foundation of Chicago house. Anybody can make a track, but you have to have that funk to really do it right.

Back in the day

Ray: When you think about Parris Mitchell, DJ Funk, Paul Johnson, Deeon, Slugo… when these guys are coming to me with music, what am I going to say, “I don’t want to put it out”? I think that kind of spread. There were so many people and it seems like Dance Mania was the only outlet for the type of music that was being done.

Victor: It was so much fun. I’d go to Funk’s house and we’d make a track in an hour’s time, just off the cuff, in one take. It was like a jam session. I’d play keyboards, and DJ Funk is a helluva programmer – he’ll program the shit out of an 808. I’m on my side, he’s on his side, and we count-off and go for it.

Gerald: I would do my tracks at home on my personal home studio. But if there were different people with different styles, influencing what I was doing, I’d make a special trip to collab with them. I was working with DJ D-Man on some tracks. I found samples, worked with them, did the keyboards, and made ‘Dooky Booty’. D-Man’s whole EP was done and was ready to be shipped out, but he liked ‘Dooky Booty’ so I gave him a copy to work with. We were going to play a party, and I wanted to be the first one to play my mix of the track. Instead, he played my mix of the track and not his own, and down the line, he pressed my version, with no commission, none of that.

“Dance Mania was the only outlet for the type of music that was being done.”

At one time, DJ Chip wanted to put out a record for Ray, and I was going through his four-tracks, and I came across the “hold up, wait a minute” vocals. I was working on a mixtape at the time and asked if I could use them, he said “whatever.” It wasn’t a big deal. I was just working with those vocals. I was working for Ray, driving back and forth, delivering mixtapes and CDs, and people were playing stuff in the car, and I’d get an idea. When I got back, I made ‘Hold Up, Wait A Minute’. I played it for Chip and he was like, “that’s cold, can you send it to me?” I sent it, but because of the D-Man thing, I gave him a bullshit ass copy.

Deeon: Back in the day, I didn’t get too many bookings in the States; I got most of my bookings overseas. It was great. I loved the raves in London, like an airplane hangar full of people. You could play anything you wanted to play over there. I could break out a country record and they would go for it. I just miss that.

Ray: If you could think back on all the people that came through Dance Mania and Barney’s Records, it’s like a who’s-who of house music: Marshall Jefferson, Byron Stingily, Lil’ Louis… these guys would just come by and kick it. You would have Funk, Slugo, Deeon, and Milton together, just having fun.

Victor: My favorite memory is just going up to Barney’s Records. From the time you got there to the time you left, you’re just laughing. Jokes flying all over the room. Everybody would come through there, not just the Dance Mania guys. Everyone in the business would come by, we had this rap group, the MF Boys, who would open for Eric B. and Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, and Ice Cube, any of those guys would come through. Guys like Jamie Foxx and Scarface. Ray would crack jokes on him, and I was like “Ray, that’s Scarface!” It was just fun, you know?

When I was working at Barney’s in ‘94, a couple of kids walked in. No one knew who they were. I put on their cassette and it blew me away. I tried to keep the tape under my drawer [laughs] but they needed it back. It didn’t dawn on me until a year or so later who those guys were: it was OutKast. They didn’t have a record out yet, but they had a deal and they were making their rounds.

Deeon: Back in like ‘94 or ‘95, I got to meet Thomas Bangalter from Daft Punk, before they came out. I met him at Gramaphone Records; the guy that I bought records from called me and said, “This guy from Paris wants to meet you, you played his track on a mixtape.” Milton and I went down and hung out with him for an hour. I had his 12” but didn’t know who he was. I haven’t talked to him since, but look at him now. I was so happy when showed us respect on the album, man, you couldn’t tell us nothing when that happened.

Parris Mitchell and Ray Barney

The fall and rise of Dance Mania

Ray: It wasn’t really that I shut down the label, it was the distribution company. With the advent of the people downloading music off the Internet, the music [business] wasn’t really what it once was. Every year, some stores would open, and some would close, but our customer base stayed pretty constant. I was servicing smaller retailers, and there was a 5 or 6 year period where stores only closed and none opened. After a while, we didn’t have the customer base to maintain the distribution company, which was the main business I was in the whole time.

Victor: Ray and his family had been in the business for a long time. When I was first working in wholesale, you had the walls lined with 45s, and maybe a few cassettes. Ray said, “You know, soon there won’t be anymore vinyl records,” and I said that’s crazy. So I left on tour with Club Nouveau, and when I came back, all the singles were on CDs and there weren’t anymore 45s hanging around on the shelves.

In ‘96, Ray said, “Pretty soon, there’s not going to be any need for record stores,” and I said he was crazy. Ray had that vision ahead of time, and I don’t know if that clicked something in my brain, but I started taking offers. I was working with K-os, Johnny P, a couple acts on Death Row. I started doing other things, and before I knew it, Ray wasn’t doing the shop anymore.

I think my last record was in 1997. I wasn’t focusing on the dance stuff at that point. I worked with Ray for 10 years at that point. But I’m a confused creative person, sometimes I want to play acoustic guitar with a singer. I kinda felt like I was in a box, and I wanted to explore more creatively.

I started doing so many other things, living a normal life, working with real estate, having another kid – there was a period where I told myself I wasn’t going to do music anymore, I was disillusioned with the whole business. I got back into it around 2009; I was working with Bump J, remixing Whitney Houston, helping start a studio.

“If we don’t do it, someone else will.”

Jamie Fry at Deep Moves reached out on Facebook and told me, “The stuff you were doing in the ’90s is relevant now. It’s probably more relevant now than it was then.” People started reaching out to us about the Dance Mania catalog, and I told Ray, “If we don’t do it, someone else will.” People want this stuff, and none of the guys will see any money for it otherwise.

Over the years, I had seen people who had nothing to do with it make claims to Dance Mania. Jesse Saunders licensed a couple of records of mine, saying he owned the catalog. [laughs] He said he owned the Parris Mitchell stuff and I told him I was Parris Mitchell – if he owned the label he would have known that! I told Ray this is getting out of hand. Ray said he would help if I wanted to press my records, but he didn’t really want to be bothered. He was living a whole other life, running a health food shop and working with computers.

I decided to test the waters, so I released my double 12” with a distributor here, and when I was doing interviews, I found out that only a few select Dance Mania fans knew who Ray Barney was. They’d ask who owns Dance Mania. My whole mission became to start talking up Ray Barney’s name. For Ray, it wasn’t about him: there’s a lot of people that deserve to make money off of their music, and I think that was more of his M.O. than anything.

Deeon: After Dance Mania, I had a couple of labels and licensing deals, so it was okay. But we missed Dance Mania.

Victor: I lot of times when we license records, we don’t see anything. We don’t get the treatment we’re used to getting from Dance Mania, the whole camaraderie is not there. Some of the other guys like Gerald and Wax weren’t doing anything with anybody after a few bad incidents. But as soon as Ray said he was doing it again, people started flocking to him with their new stuff. I think Ray realized that if the only way some of these guys were going to do anything was if he got involved.

Ray: The challenge is that most of the fanbase is overseas. This is why I’m glad we connected with people overseas, so we’re not dealing with a territory we’re not familiar with. Instead of marketing it locally, we’re marketing it to a whole different fan base. Before, we weren’t even marketing, we were just doing what we wanted to do. Now, we’re trying to fill a need.

Victor: Now it’s supply and demand. It’s a specialty market, doing vinyl only.

Deeon: I’ve got a double album coming out; I can do whatever I want to again. I see the old gang back together, I want to do this.

Gerald: Whatever tracks I’m making now, I try to keep it in that old flavor or pretty close. I keep going back to that sound and that feeling. Keep it ghetto house style, keep it Dance Mania. It had its own unique sound.

Ray Barney, Nina Kraviz, Parris Mitchell, and singer Curtis McClain

The next generation of Dance Mania fans

Brenmar: Growing up in Chicago, I was hearing Dance Mania records before I really knew what Dance Mania was. I vividly remember going to house parties and dancing to DJ Funk, DJ Deeon, and Paul Johnson records while girls grinded up on me. I didn’t know it was such a Chicago thing ‘til I left Chicago.

French Fries: When I was 16 and listening to hip-hop, I met Jonathan [Chaoul, ClekClekBoom’s Ministre X], who was living near my house. I heard he was a DJ. I didn’t know at all about electronic music, like house music and stuff. But he gave me a CD and it was only Dance Mania, Trax, and Strictly Rhythms. That was the first house music label I listened to. It was one of the most important labels for me, and it still is today.

Bok Bok: Dance Mania is at the foundation for me. It’s integral to what I do, in every way. With how we came up and how we’ve done things, Dance Mania is a part of it.

Nina Kraviz: About 10 years ago at the Hardwax record store, I heard a DJ Milton record and it instantly linked with my personality. That raw vibe, at times sloppy and sexual. Badass beats, most of the time recorded from the first take, out of sync samples, blurry frequencies, straight in-your-face vocals. Very expressive, yet unpredictable, like a human.

Chrissy Murderbot: I first heard Dance Mania stuff being played at raves in the Midwest in about 1996 or 1997, although I didn’t realize at the time that so many of those big tunes were on one label. I loved house but also really loved jungle and happy hardcore and stuff like that, so it was big to me to hear a type of house music with that faster tempo and higher energy.

Bok Bok: In all honesty, I came across Dance Mania how most people probably did: you hear something like DJ Assault’s ‘Ass-n-Titties’ — which isn’t even on Dance Mania — and you start catching up and downloading on Limewire. That’s how I found DJ Funk and DJ Deeon; that was the entry point – the more quintessential, mid-90s stuff.

French Fries It was the easiest way to go from hip-hop to electronic music. It’s tough to go from Southern hip-hop to Berlin techno.

“It’s genuine and it doesn’t tend to be perfect. It’s just the way it is.”

Nina Kraviz: The way they recorded everything at once to keep a real emotion and to capture the magic of the moment rather than polishing sounds until they reach perfection has been my biggest inspiration. It influenced me a lot as a producer and a DJ. That’s how I make my own music.

Brenmar: I used to buy records at this spot called Hip House in North West Chicago; they would always have all the classic Chicago ghetto reissues. This was the early 2000s, and for me, so many of these songs were already local classics. I still reference Dance Mania constantly when I make club music — it’s impossible for me not to.

Chrissy Murderbot: I can’t name just one Dance Mania title I tend to play out. My big ones are Jammin Gerald’s ‘Pump That Shit!’, ‘Hold Up Wait A Minute’, ‘Aw Shux’; Waxmaster’s ‘Work Out’ and ‘Stop Screamin’’; DJ Deeon’s ‘The Freaks Remix’; DJ Funk’s ‘Pump It Remix’ and ‘Ain’t It Funky’; DJ Milton ‘SouthSide Beatdown’…

Nina Kraviz: From the DJ point of view, Dance Mania is arguably the most challenging record label. MPC recorded beats are sloppy, changing speed all the time, and some frequencies and overall levels are just charmingly fucked up. I sometimes joke that if there were an exam for a DJ, it should be to mix 10 Dance Mania records without messing the mix.

Bok Bok: I was pretty surprised to be able to remix Parris Mitchell. He hit me up to do some actual collaborations, and within a few hours of that, Deeon got in touch with me, and was like, “hey, let’s work.” So that pretty much made my year.

Nina Kraviz: I think the main charm of Dance Mania is its mystery. There’s always been a myth around the label. Not many people have had access to the entire catalog. As a happy owner of more than a half of it, I can say its been quite a journey. Surprisingly, after so many years, it still happens that some really great Dance Mania records pop up out of nowhere and I think “how the hell could I miss that one?” But it always feels so great to find a hidden gem, and that opportunity makes a lot of people excited about the label. A rare Dance Mania record is one of the biggest record digger’s trophies and strong motivation to continue the hunt.

Dance Mania is a unique label that was created at a very special time and in a very special city. It’s a role model for real underground labels and it’s been symbolic for vinyl lovers. It has a very distinct, signature sound. The way the music was recorded and how it was delivered brought each record a lot of character. It sounds so real and human. It’s genuine and it doesn’t tend to be perfect. It’s just the way it is.