Alex Alekperov opened his record store in Baku, Azerbaijan, in 1979, long after the USSR had begun to relax its attitude to western culture.

Alekperov had emigrated to the States in the ‘90s, first to Staten Island then to Philadelphia. He now works as a computer programmer in the pharmaceutical industry, and he never stopped playing guitar – he currently plays weekly in north-east Philly with the Alabama Sam Blues Band. His High Fidelity days are long gone, but he was excited to tell his story.

Interview by Andrew Friedman

When I was in fourth grade, I was searching the radio and socializing with kids who were interested in western music.

I was listening to The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Elvis and Bill Haley – that was the starting point, which I found through the radio and black market records and tapes. At that time Iran was under the Shah, not the Islamists, so we were listening to all the western music being broadcast in Iran. We had a piano and my parents wanted me to have a musical education. My first teacher was an accordion teacher who I didn’t like.

I had already fallen in love with western rock, and when the teacher wouldn’t give me that stuff, I started teaching myself blues and rock and roll on piano. In 1968 I made my first electric guitar. You couldn’t buy an electric guitar then, so I got a piece of wood, cut it into a body, attached an acoustic guitar neck to it, and grabbed the pickups from telephone lines. So that was my first guitar I could play with an amp.

I came back to Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, from the military in 1974, and was assigned to a sports store. The big director of that store saw in my resume that I was a musician and that I’d been playing in the military band in Moscow. They were opening a record store and asked me if I would like to take over. Of course I agreed, because I didn’t like dealing with school supplies – that was my department. So around 1976 I opened my first record store. After developing it successfully in the eyes of the city, they decided to assign me to the special record store under the Culture Ministry, not the Trade Ministry. It was an honor. We opened the store in 1979 – it was on TV!

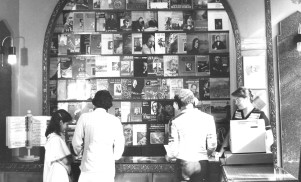

The store was very small. It had four departments — national and folk music, variety music [Soviet pop and rock], classical, and then everything else including children’s music. There was a desk for each department and a sales girl behind each desk, with all the records displayed behind the shelf. You would ask to hear something, listen to it on the record player, and if you liked it you would go to the cashier and pay.

“We had lots of tourists coming from other communist countries to buy classical and western records”

The only record company in Russia was called Melodiya, and it was run by the Ministry of Culture. Melodiya only had 16 record stores in the whole Soviet Union, and every republic had one store in the capital – there was one in Tallinn in Estonia, one in Tblisi in Georgia, and my store in Baku. My store was like a destination. For one, we had all the tourists.

The store was right in front of the Maiden Tower, the most prominent landmark in Baku and the most common site to visit in the city. The tourists would come see the tower and then notice the record store, so of course they would come in. Our interior was nice — we spent a lot of money. We had a whole room done up in gesso, painted with miniature drawings of 15 traditional Azerbaijani instruments. People would take photographs.

I did the research and the advertising, and I was looking at magazines around the world to see how I could develop my store. We did a lot of outside sales – I would go to all the companies at lunchtime and put the records in the hall so that people could could come and buy them and it would save them time. I was at every big company in Baku at least once a month.

My friends were in the hippie movement and into rock and roll, but there wasn’t much of a young population and it was only specific groups that were interested in western music. Most people in Azerbaijan were listening to the national music – mugham and Azeri dance music. Mugham is very important – it’s like jazz, actually. But where Russian people were listening to Russian music, and Georgians were listening to Georgian music, Baku was one of the most international cities in the Soviet Union, and we were listening western music. In 1968 it was the Beatles and Rolling Stones, the Doors and Canned Heat – mostly English and American bands. We were buying records on the black market every Sunday morning. It was expensive — from 50 rubles up to 100 rubles – and 50 rubles was half the average worker’s monthly pay! So we were also recording songs off the radio and exchanging tapes, mostly British Invasion music, like the Beatles, and American bands.

We had lots of tourists coming from other communist countries, like Romania and Bulgaria, to buy classical and western records – not because they couldn’t find them at home, but because the prices were actually cheaper here. That’s because all the prices were set to what people were earning. In the Soviet Union people earned 100 rubles a month, and it was 1.45 rubles for a classical record and 2.15 rubles for pop records. In Bulgaria, the same record might cost twice as much.

“All the records were coming from Moscow, and they had no idea about western music”

We never got original presses of American records. The only records we legally could have were from the state label, Melodiya. In 1985, when Mikhail Gorbachev relaxed the policies, they were able to reprint some records with a license, like Paul McCartney and the Rolling Stones, but that wasn’t the case in the beginning. Sometimes we would receive records from other communist countries like Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and East Germany. If Russia didn’t want to buy a license, they could just buy the records from these other countries, but only in very small amounts — perhaps 100, 200, or 500 copies for a city with one million people. There was a big demand for those records.

I didn’t have much interaction with Melodiya. I went to conferences in Moscow two or three times, once for almost a month of training with all the shop owners from the 15 republics. We met the personnel and the people in the company, but that was the first time I saw them – I didn’t get much help. So I was in charge of our stock – I would go to the warehouse and make the decisions about what to bring to the store. I knew which records would be in demand and which wouldn’t. All the records were coming from Moscow, and they would stick on a label saying “this is good” on some records and raise the price a little bit. But mostly they had no idea. Especially with western music — some of the store managers had never heard of the Rolling Stones, so I’d go to the warehouse and grab all the copies.

There was no resistance from the government. It was something positive and new that they could report to the higher-ups. The city could report it as a good thing going on, and say that the people were happy. I also had a very good relationship with all my customers. The credo for my team – I had about six people – was to never say no to the customer. Even if you don’t have the record they are asking for, don’t let the customer leave unhappy. That made us popular. When I came to the US I received a lot of calls from my customers who had also emigrated.

We just had a different atmosphere in our store. We had parties with musicians coming in and we really tried to make a difference, not just in terms of record sales but to the musical atmosphere in the city. BB King even came in! I spent three hours talking to him and his band in 1979, when he was touring the Soviet Union and played four days in Baku! He was amazed, he couldn’t believe he was on the other side of the world and all the tickets were sold out. I had poor English, I guess I used sign language, but I told him I loved the blues and had grown up with it. I had a girl make him a pack of about 15 records — Russian, Azerbaijani, jazz and classical.

Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown also came through — he wrote a song called ‘Near Baku’ after his trip – but he was the only other American artist. Everybody went to Moscow, but Baku wasn’t on their route. But because of Mugham and its diversity, many musicians were very successful. And today Baku is one of the biggest jazz venues – every year they have a big jazz festival with great musicians. They’ve had performances from Herbie Hancock, Joe Zawinul when he was alive, and George Benson.