For some fans, the entire idea of who William Basinski is remains stuck on a rooftop in Brooklyn in the fall of 2001.

He’s the artist — after decades of fighting to be understood, finally ready to give up on it all — who witnesses the most significant tragedy of a generation while simultaneously composing the single most important piece of art to help heal it.

It’s a story so tragic and inspiring that some part of our collective perception will repeat it, like one of the Disintegration Loops, until we burn out. That’s what happens when you become a living legend. The legend will never die, but fans could do with an update on the man living it. That’s because Basinski left Williamsburg years ago, and that Brooklyn, his Brooklyn, is mostly gone – replaced by a pricier, newer borough that is in turn itself being replaced.

Now, when he’s not traveling the world performing or in Austin with his impeccable collection of vintage American cars, he lives in a quiet part of Los Angeles. Our perception is stuck in the past, but Basinski is not. As he puts it: “I try to stay in the moment — and the moment is eternal.”

As I walk up to his Mar Vista home a melancholic loop spills through the screen door. It should feel at odds with the lovely view, the sunny chime of the doorbell, and the smiling man coming to invite me in — shirt off, cowboy hat on. But it doesn’t. Nothing is at odds, everything falls into place. This is Billy Basinski and he’s just invited me into his home.

It’s a home he’s had since 2004 with his partner, artist James Elaine, though it wasn’t until 2008 that he finally left Arcadia, his legendary Brooklyn loft and art space, once and for all.

“I ended up piling more people in the loft in Brooklyn, mostly staying out here and coming back every few months to scare people and work in my synthesizer studio,” he says. “I’ll always miss my big palace in New York, but towards the end it just got so … you know what happened to Williamsburg. I hated to leave it, but we had to.”

We sit in the backyard with a canopy drawn to shield out the LA sunshine, sipping beers as birds chirp in the garden behind us. He’s hilarious and just a little vain — though handsome enough to justify it and self-deprecating enough to balance it.

He’s describing a vocal-focused project from his “goth, Vampire L’Estate days” which never saw completion when he first brings up his most famous record.

“…anyway, that computer eventually died — typical Disintegration Loops story with me,” he laughs. It’s so casual, but it says so much. He jokes about his works in a way that exudes the decades of love he’s put into them, like someone teasing their partner or kids.

Still, that bicoastal transition means that while this home has had a decade to be settled into — his mini-Eden of a garden proves it — the equally methodically designed elements transplanted from his Arcadia are still finding their place. This past year, however, seems like a breakthrough.

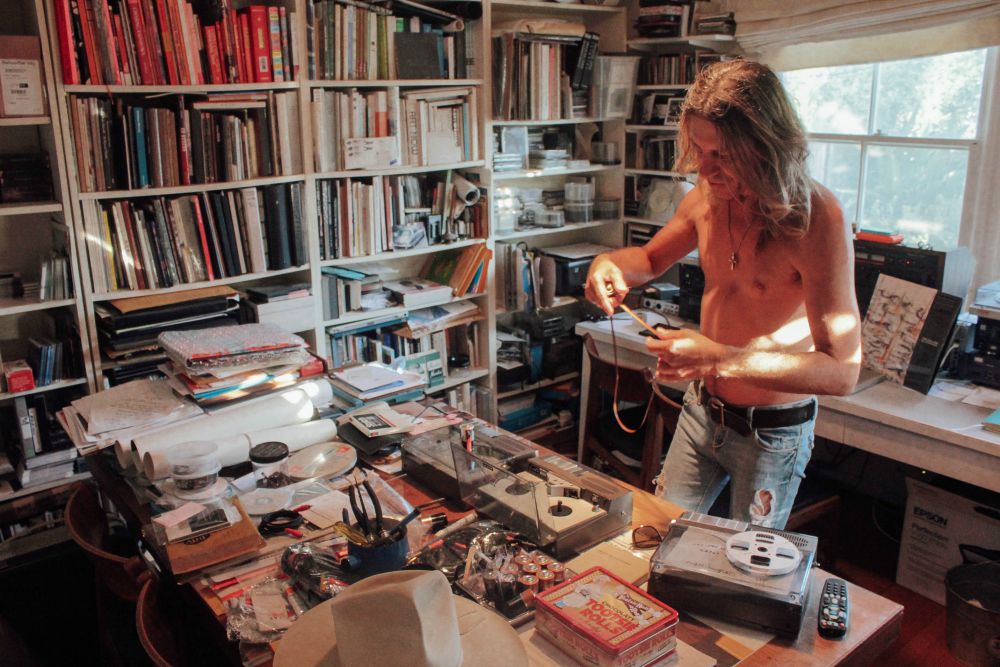

Basinski has recently redesigned his guest bedroom as a studio containing the synthesizers, the cabinets, the same equipment he used to travel to New York to work with. It’s a work in progress, and there’s still troubleshooting, wiring, and a few new consoles that need to be installed, but it’s a work of beauty. And there’s more. There’s the tape room.

The tape room is a walk-in treasure chest containing Basinski’s career. Milestones and achievements and memories are nestled together wherever you glance: the sheet music to the live performance of ‘Disintegration Loop 1.1’ from the Met in New York; handpainted editions of Melancholia; the original Vivian & Ondine loop which he keeps in a small tin Tootsie Rolls lunchbox and affectionately refers to as “a little piece of spaghetti”.

He shows me an old Norelco reel-to-reel he used to use before switching to smaller battery operated players. It’s a stunning piece of machinery, which he carefully places a loose piece of black tape inside. Pulling them taut with two heavy batteries placed at the top as capstands, he flips a switch and suddenly the machine bursts to life, playing the final section of ‘The Deluge’ from his latest album Cascade. Even with a view from the driver’s seat, the recording loses none of its ineffably sad beauty.

“I fucked this one up, it has a big glitch in it,” he says as I nod mock-knowingly at the self-criticism. “Of course, they love that!” he laughs as I nod much more honestly. He’s right. We do.

Cascade is a recent project, but one of the curious qualities of Basinski’s catalogue is the way he staggers releases with works that can date back as far as the late 70s. His archives of loops are vast and the numbers remain mysterious (“There’s stuff,” he says coyly). The title piece of his 2013 album Nocturnes is dated to “circa 1979-80″, but the following ‘Trail Of Tears’ came from 2009. I ask how he makes such a cohesive album with recordings separated by so much time.

“I think I just want to give my fans ‘an LP’s worth of tunes’, as Todd Rundgren said. There was something about it. It just wanted to go on there, so it did.”

He often describes his work like this — he thinks of the pieces like his kids. One of Basinki’s great talents is letting these loops crawl and grow and evolve. And, yes, some of these kids are reaching their twenties and thirties. “Get the kids out to work — mama’s tired!” he says, and we laugh, but truth of that statement is no little thing and he grows more serious. For the first time since walking through the screen door I think of that rooftop.

“The thing is, I pined for years when I was 25, 30, 36 — young and gorgeous — just going, ‘People aren’t getting this stuff! What do I have to do?’ And then I went on and played in bands, but I kept doing my work. So when it finally came around and Carsten [Nicolai, Raster-Noton founder] wanted to release Shortwavemusic …” He pauses for a moment. “I’m just thankful for that. I never thought I’d see the day.”

Around then the evening hit that magic hour glow that California does better than almost anywhere, and we walk through the garden. He wears a NASA shirt — where his father worked. Gardening in Los Angeles is mostly just cutting things back, he says, but the sheer beauty makes that seem impossible.

There’s a 60-year old orange tree, the same tree that he stood by, picker in hand, for an old press photo. The picker is there too, leaning by the tree. The fruits are only just growing, but by Christmas time there will be thousands. There’s a persimmon tree which sprouted up on its own, and hidden away are a trio of intricately designed Asian statues. Two girls and one boy, rescues from Arcadia. The palace is gone, but there are more out there.

“I travel a lot. I go all over the world and there are these big fabulous rooms I can perform and it’s like I get another place to try it out in. And here I’ve got my little garden,” he says. “I’ve got my flowers and butterflies and hummingbirds and I find it quite peaceful. I can hear my work here. I can’t be too loud, because it’s quiet, but… I make my noise.”