When it comes to cities renowned for their musical heritage, Dusseldorf is pretty unassuming.

It rarely features in lists of major music cities worldwide, but such accolades are usually reserved for destinations that fit neatly into the conventional rock canon. Still, electronic music is hardly a spring chicken and it’s strange to think that these sounds, which once seemed so futuristic and avant-garde, have become heritage fodder too. Dusseldorf’s music trail is readily discovered by the cognoscenti, but it’s not exactly trumpeted from the rooftops. The tourist board launched the We Love Music walking tour in 2011 on the back of the city hosting the Eurovision Song Contest, though it does cover Kraftwerk at the more credible end of the spectrum.

For the krautrock faithful, there are certainly plenty of sights to take in and history to soak up. (As David Stubbs’ wide-ranging book Future Days shows, the very term ‘krautrock’, while fraught with controversy for some, has been accepted, albeit ironically, by many of the scene’s players.) Besides the obvious twin behemoths of Kraftwerk and Neu!, Dusseldorf gave us the art punk of DAF (Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft), the proto-industrial of Die Krupps, and the high-concept, ZTT-masterminded glossy pop of Propaganda.

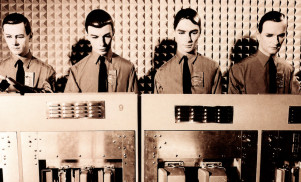

Above all, the city gave us Kraftwerk. The band members are notoriously private creatures, preferring to keep their enigma alive than let us see behind the curtain. The original Kling Klang Studio, where they worked from 1974 to 2008, producing all of their classic studio albums, can still be found on Mintropstrasse, a slightly grubby street in the red light district, minutes from the main train station. The Elektro Muller sign still hangs over the door, but there is no plaque. When I visited, a solitary traffic cone was the only oblique clue that this was the spot where wonders were hewn. These days the band work in a studio 20 miles out of town, in an undisclosed location. Public visits are not exactly encouraged.

Various anecdotes have emerged over the years confirming the band’s distant persona, like the fact they had a phone in the studio, but would only switch it on when they were expecting a call. When Chris Martin sought permission to use the melody from ‘Computer Love’ for Coldplay’s song ‘Talk’, he received a handwritten reply from the band via their lawyers. It simply read ‘yes’.

In a recent interview with Rolling Stone, Ralf Hutter, Kraftwerk’s co-founder and the sole surviving member of their iconic 1970s line-up, proclaimed that the band “came from nowhere”, and while this may sound a shade arrogant, Kraftwerk’s sound was so startlingly unique that indeed it’s hard to argue with this year zero statement. But every genre of music has its roots somewhere, doesn’t it? And why did such an extraordinary wellspring of talent emerge from Dusseldorf in the ‘70s and not some other German city?

It’s a question that Rudi Esch, of ‘80s electronic body music pioneers Die Krupps and later La Dusseldorf, has been immersed in answering lately. He’s the author of a book titled Electri_City: Electronic Music from Dusseldorf, an oral account of the city’s early ‘70s scene which proclaims Dusseldorf as the “Memphis of electronic music.” Rudi has also organised a conference of the same name, which this October saw Heaven 17 perform in the city for the very first time, while OMD’s Andy McCluskey, Mute founder Daniel Miller and Cabaret Voltaire’s Stephen Mallinder discussed the impact the city has had on their work

“The city became a historic melting pot of music, art, fashion, design and advertising. Plus, Dusseldorf always had money,” says Esch. “The ‘70s were a time of huge freedom when everyone was looking for a creative outlet, artists rubbed shoulders with musicians. In fact I would say that the art academy [Kunstacademie Dusseldorf] is more important to Dusseldorf’s experimental electronic heritage than the city’s music conservatory.”

The lynchpin at the Kunstacademie was Fluxus artist Joseph Beuys, whose sculptures still dot the city today, like the surreal stovepipe emerging from the walls of the Kunsthalle Dusseldorf. Beuys ran the Academy and was instrumental in setting up the Creamcheese Club, which hosted regular art happenings including the very first Kraftwerk gigs. Today, it’s a fairly anonymous, cream-painted office block, but from the late-60s to the mid-70s it was a hotbed of creative expression, featuring psychedelics, murals by Gerhard Richter and much ecstatic, wigged-out dancing to motorik beats.

The more traditional music conservatory was nonetheless an incubator for the young Ralf Hutter. It was here that he met Florian Schneider, sparking a creative partnership which spanned 40 years. According to Esch, simple geography had a decisive role in shaping Dusseldorf’s output.

“Dusseldorf is in the far west of the old BRD [of pre-unification Germany]. We’re close to the Dutch border and its major international airport, which brought models, photographers and of course drugs into town. Then there is the famous party district of the town, the Altstadt. The Altstadt, or old town, is near the Academy and this melange of art and excess created many great bands.”

Today the Altstadt proudly holds the title of the “world’s longest bar” due to its high concentration of watering holes. In Wolfgang Flür’s lively memoir I Was a Robot, the Kraftwerk percussionist recalls a few ribald tales of nights on the tiles and in discos, flirting with groupies and carousing into the small hours (which embarrassed the band’s other members enough for them to pursue legal action to prevent their indiscretions from surfacing).

Flür’s own band the Beathovens were regulars on the Altstadt’s live circuit, plying the Brit-centric sound that permeated Dusseldorf’s music scene in the ‘60s thanks to the British Forces Radio, which dominated the city’s airwaves. They achieved moderate success too, culminating with a support slot for The Who. The city’s strong economy meant that aspiring musicians could afford to buy whatever instruments and kit they needed. After the second world war, Dusseldorf was one of the chief beneficiaries of Germany’s economic comeback. The nearby Ruhr Valley fizzed with electronics businesses, adding to already potent powerhouse of mining, finance, media and automotive industries.

Schneider and Hutter were both from prosperous backgrounds, coming from the upmarket suburb of Oberkassel across the Rhine, which even the tourist board’s literature describes as snooty. Their elitism has been noted on numerous occasions, especially by Flür in his book. According to DAF’s Ralph Dorper, Kraftwerk were not much liked by the punks who emerged later in the decade, who saw them as firmly establishment. Schneider’s father, Paul Schneider-Esleben, was the successful architect behind the busy Cologne-Bonn Airport and the Mannesmann building, a skyscraper on the city’s waterfront which today shares the limelight with Frank Gehry’s leaning towers.

Schneider-Esleben had roots in the art scene too, being a contemporary of Beuys and the radical Zero Movement artists such as Heinz Mack and Gunther Uecker, who would stage exhibitions outside of the confines of art galleries in whatever spaces they could find. “Beuys had this credo that everyone was an artist,” explains Esch, “so he accepted anyone to study at the Academy. Beuys had a radical, new way of thinking, and of course he loved music. He was the one who encouraged Eberhard [an early Karftwerk member] and Florian Schneider to play their first shows at the Creamcheese. Because of his influence, you could play shows at the Academy or just have your rehearsal room there.”

As the decade progressed, while Kraftwerk and Neu! toured abroad and built their international reputations, Dusseldorf grew into a music mecca. The Rathinger Hof opened in 1975, a sweaty, neon-lit bar that spawned a new generation of punk acts, like DAF, who embraced the energy of punk but channelled it through synths instead of the typical “two chords and you’re away” guitar set up.

“Like the Creamcheese before it, the Ratinger Hof was very important to the growth of the city’s music scene,” says Esch. “Both were designed by artists and therefore attracted new groups of people. What Dusseldorfers just called the ‘Hof’ could well be compared to CBGB’s in New York, and it had the same impact on the city’s new wave scene. Here bands like Die Krupps, DAF and Der Plan all started.”

It probably helped that similar whirrings were emanating from kindred spirits in neighbouring cities. In Cologne, only 40 minutes’ drive away, they had the Studio for Electronic Music. Set up in 1951 by the German radio station WDR, it was the first of its kind in the world, broadcasting strange electronic sounds developed by the likes of Karlheinz Stockhausen and his mentor, physicist and experimental acoustician Werner Meyer-Eppler, through the night. Cologne also produced the third side of krautrock’s golden triangle, Can.

The punks understandably sought to break away from the previous generation’s efforts, but it’s still the first half of the ‘70s that’s remembered as Dusseldorf’s golden era. Many acts crossed over, swapped members and collaborated. Neu!’s Klaus Dinger had a spell in Kraftwerk, as did his partner Michael Rother. Also member of both bands was Eberhard Kranemann, another Academy alumnus who Esch describes as “having an anarchistic style in playing his Hawaiian guitar and bass.”

Before the ‘70s the main form of popular German music was Schlager, a schmaltzy strain of easy listening that recalls the sentimental excesses of Eurovision Song Contests gone-by. This was the cultural vacuum from which Kraftwerk and their contemporaries emerged. (The city still acknowledges Schlager, however – on the music tour I’m shown a window display in a funeral parlour in tribute to Udo Jurgens, a much-loved local singer who had recently died.)

Wolfgang Flür remembers these years as “a fantastic time when everything seemed possible. The first synthesizers were instruments that cried out for a new musical path. You didn’t need a music education to use them. Musical virtuosity would at most be replaced by a boffin’s hunger for knowledge. Suddenly everyone was able to make music.”

Some 25 years after the end of the war, Germany was forging a new cultural identity, with music at the vanguard.

“I am not sure we knew what we were putting in motion at the time,” says Flür. “We consciously broke with the musical tradition of the Allies and were looking for a European identity. We wanted to oppose the superiority of Anglo-American music with something frightfully German. It felt strange that people loved us exactly for that reason.”