With Dolphins Into The Future, Lieven Martens Moana found his footing just as the noise scene started to explore new age music. Miles Bowe talks to the Belgian composer about his gorgeous new album and putting the Dolphins Into The Future moniker out to sea.

Field recordings are often more about listening than recording, and nobody listens like Lieven Martens Moana. As Dolphins Into The Future, he blended new age, early synthesizer music and tropical field recordings making one-of-a-kind soundscapes during the noise boom of the mid-2000s. Now, under his own name, his music is even more poetic.

While his previous albums have contained elements of new age and exotica, Martens tells me he sees his work as part of a larger tradition of programme music and classical Romantic and Impressionistic composers like Berlioz and Debussy. Programme musicians create an extra-musical narrative around a work, and on his new album Idylls, Martens uses a suite of personal sounds as if they were parts of a diary. Disinterested in the outdated escapism or sensationalism offered by exotic field recording, he prefers to see his album as a self-portrait.

Idylls, out now on Spencer Clark’s Pacific City Sound Visions, features equally impressionistic moments outside of field recording too, including the four-part ‘Transcript from Ambae Island’ which moves through an aria, two scherzos and a coda, as delicate piano keys and fluttering synths hover. The closing track is recorded on an actual 19th century wax cylinder; it’s a fitting end to an album that sounds as lush and ornate as ancient ruins.

What do you look for when you make a field recording?

These recordings always have a musicality to me. Even the dullest recording has this. I create them a lot of times just out of nowhere, and other times I record them quite purposefully. Making a very normal recording in extremely beautiful environments holds for me a fantastic thing and when I mix them in my music in the end, I just use them as part of the symphony. A cicada could mean dryness, a motorboat could imply transportation, fishing and isolation. A wave means communication, etc.

With field recordings, I don’t want to hint at things like escapism (dreaming of tropical tropes) nor sensationalism (very weird animal sounds, you know, throwing the good old mic inside an iceberg and all that horrible stuff), but I accept when people see it as escapism.

When you play live, Wietske Van Gils projects tropical images, distorted with marbles and water. It works in such symbiosis with the music. How did that develop?

While we were on holidays we would take all these pictures. Not just tourist ones, but close ups, in a personal way, like using them as sketches. I don’t need a recorder or a picture to memorize a place and I certainly don’t need to start making pictures since, well, the latter is something that is out of my scope. I’m a musician, in the end.

I noticed that with doing that, watching through the seeker to an environment, I trained myself subconsciously to become a better musician. I started to be very aware of sounds and the structures of things. It helped me build better albums. It was a way to force myself into concentrating on lines from cliffs, different bird melodies, et al. The picture helped us, or at least me, to learn how to aestheticize things and look differently at those same things. They were never taken with the idea of creating visual works. Maybe a record cover, yes, but that’s all.

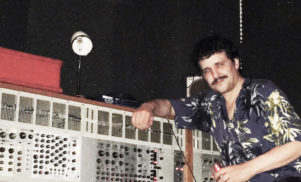

The use of them in the music seems like a good idea, with Wietske creating those animations, it could be another level for people to enter our world, my world. We still work it out in a very modest way though. It shouldn’t be distractive or sensational, but especially in bigger rooms, it could help the people to have a focal point instead of staring to my mustache from far away.

“With field recordings, I don’t want to hint at things like escapism nor sensationalism.”

The notes and stories provided with each song on Idylls make it feel like an aural travel journal. You recorded the last track on a wax cylinder. Was that a difficult process?

I wanted to tell these stories since, in this way, the album almost turns out to be a self-portrait. Even the most die hard programme musician, in the end, talks about himself. I hope if you listen to the music, and then maybe afterwards read the text, you’ll be transported for a second inside this train of thought. The wax cylinder was important to do, not because it’s cool or something, but for the reasons I talked about in the text. It hold such a dramatic history — and yes, it’s also okay to approach as something that sounds cool.

You work under your own name rather than Dolphins Into The Future now. What made you shift away from the moniker?

That story was over! [Laughs] It was, in the end, a prison for me. Doing works under my own name gave me way more space to go in a direction I wanted to go. A more difficult one – yet therefore not a more niche one.

I think the Dolphins thing in the end became too much a strange connotation. It created the expectancy of all-out new age music. Which is a genre I like, but never ever – nor did I ever imply this – did I want to break out completely on this path. It was, however, cool under the Dolphins moniker, to explore this music and its tropes and bring them inside a more experimental environment.

So with stopping using the name, it’s not that I wanted to break with the past. It’s important to explore strange combinations of music and it’s equally important not to fall in the trap of “spoofing” or something like that. You know, creating pastiches. There’s a thin line though, however the Dolphins name kinda pushed me over that line a little bit. Under my own name, everything is possible!

What influence has exotica music had on you?

It obviously had [an influence]. I like certain exotica things a lot, but as you might’ve guessed, it’s also a strong guidance for me of how to not make music. My music never has a starting point “of being against something”, but when you create things that refer to other things, there will also be criticism necessary. In the end, I think an artist starts creating things since she/he thinks there’s a lack of something.

It started around 2010 in my endeavor to create the ultimate new programme music, which I still kinda want. I had a lot of inspiration from new age music, since that’s very programmatic, but when I started reading Pacifica writers like Albert Wendt, my mind completely exploded. I don’t know why, but I found so much inspiration in it. They all had a very modernistic approach to things and their metaphors are unbeatable. They also, next to all this beauty, have a very powerful gift to transfer criticism in their works.

All this is not so different than Debussy who had people writing then about strange musical structures, Maori singing, etc. I think every composer should broaden himself and completely follow through with studying the things she or he thinks they’ll need. You won’t find enough in exotica and especially in the “nu-exotica” or “faux exotica”, whatever that may be or not be, since that is more a world were artists reflect on themselves. Which is amazingly fine, but it won’t create a new composer who has built his own complete note system… something which I’m very, very far off. [Laughs]

Yet once one is prone to exoticism. It’s always a labour of containing, sustaining. It’s easy if you let yourself go, it gets cheesy and the danger of neocolonialism is sometimes lurking behind the door. I think for me it’s more and more important to share the darkness or at least give a more objective story, instead of what I would do before, indulging myself in self-inflicted naivety. I don’t say that everyone should do it, but also, if you draw so much inspiration from something, it seems completely uncalled for to keep behaving in an off-grid way. Like, “Thanks bros, I’ll dance the hula now and leave it there.” So, background is necessary.

You’ve had a long relationship with Spencer Clark and are putting out Idylls on his label Pacific City Sound Visions. How did you first cross paths?

We crossed paths when he came to Antwerp first. Although our approach to create music is relatively far away from each other, and we have different views – mine’s more mundane, I guess – we have much in common. I find him very inspiring, and I guess he’d say the same about me. I said somewhere before that modern music would be more boring without him, and I still believe in that. He is a person that goes the long walk to master an art form which he can completely call his own. Like you know, he could call me and say “Hey man, my next album will be action movie music.” You can never guess how that will sound … and for that he should be admired.

Miles Bowe is on Twitter