An early champion of electronic music, Suzanne Ciani is one of the genre’s true pioneers, producing a run of influential albums and even crafting sound effects for Coca Cola and Atari. Her latest project is Sunergy, a collaboration with young composer Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith, another disciple of the Buchla synthesiser. DeForrest Brown speaks to the duo about their deeply human take on synthesis.

The chance meeting of Buchla synthesizer pioneer Suzanne Ciani and emerging Buchla composer Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith happened two years ago at a community dinner in the tiny coastal town of Bolinas, just north of San Francisco. Struck by the coincidence of finding a fellow disciple of Don Buchla’s complex machines, their acquaintance has swelled into a symbolic collaboration on Sunenergy, out this week RVNG Intl., an album which represents the closing of a generational gap and a twin meditation on the cyclical rhythms of sun and sea.

Sunergy is the latest record in the Brooklyn-based label’s FRKWYS series of cross-generational collaborations, which most recently offered transportive meditations from Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe and Ariel Kalma and guitar melancholia from Steve Gunn and Mike Cooper. Ciani and Smith have orchestrated their varying approaches to their Buchla machines (built by the company Don Buchla founded in 1963 in Berkeley, just a couple of hours drive from Bolinas) into a bed of spiraling synth percolations and interlocking legato melodic patterns; a Vivaldi-like stream of aquatic sounds grooved in poetic randomness. Designed as a synth odyssey, Sunergy’s production is also a shared expression of Ciani and Smith’s hometown, its history as an artistic haven and their own seemingly fated meeting.

Ciani, who has lived in Bolinas since leaving New York City in 1992, was an early adopter of electronic music whose work with the Buchla 200 in the 1970s exposed many curious listeners to the possibilities of synthesised sound production; she even taught Philip Glass how to program his first synth. Smith, meanwhile, has become known in recent years for her own fluid and multi-instrumental approach to the self-contained, briefcase-like Buchla Music Easel. Her most recent album EARS, released on Western Vinyl in April, blurred electronic production with woodwind arrangements and vocal processing to conjure invigorating, organically mutating soundscapes.

In the 1990s, Ciani drifted away from her Buchla and returned to the piano, releasing a number of more classically oriented albums, but the increasing popularity of experimental electronic music in recent years, proved to her by a new generation of listeners with an appetite for her early work, has left her overjoyed. “It’s so amazingly different now, because in my day there was this huge gap [between artist and audience]. Nobody even understood that the sound was coming out of the machine. It was like the dark ages in a way. It took so much patience.”

Back in In the ‘70s, she recalls, people would ask where her tape recorder was after she performed, not understanding that her music was actually generated by her machine. “There was no shared environment then, culturally, for what [electronic music was]. Nowadays the environment is refreshing in that everybody seems to understand and it’s on a much broader level of interchange and there’s a conversation going on. I never thought I’d live to see that. Over the years that this was evolving I was completely unaware. I had gone back to the piano. [Finders Keepers label head] Andy Votel was the one that reconnected me with my past, because he insisted on putting out early electronic stuff.”

Ciani and Smith bonded as the elder synthesist began her reemergence into electronic music by getting to grips with the latest generation of technology. “I was getting ready for a tour with Andy [Votel] and Demdike Stare’s Sean Canty [as the hypnagogic turntablist and synthesist collaboration Neotantrix] and actually had this thought that Kaitlyn would teach me Ableton, because I don’t use Ableton. She started helping me in my studio and she was very professional. I appreciated her discipline and professional nature, and then she suggested this project.”

“The synths were side-by-side and we were actually connected by an umbilical cord”Suzanne Ciani

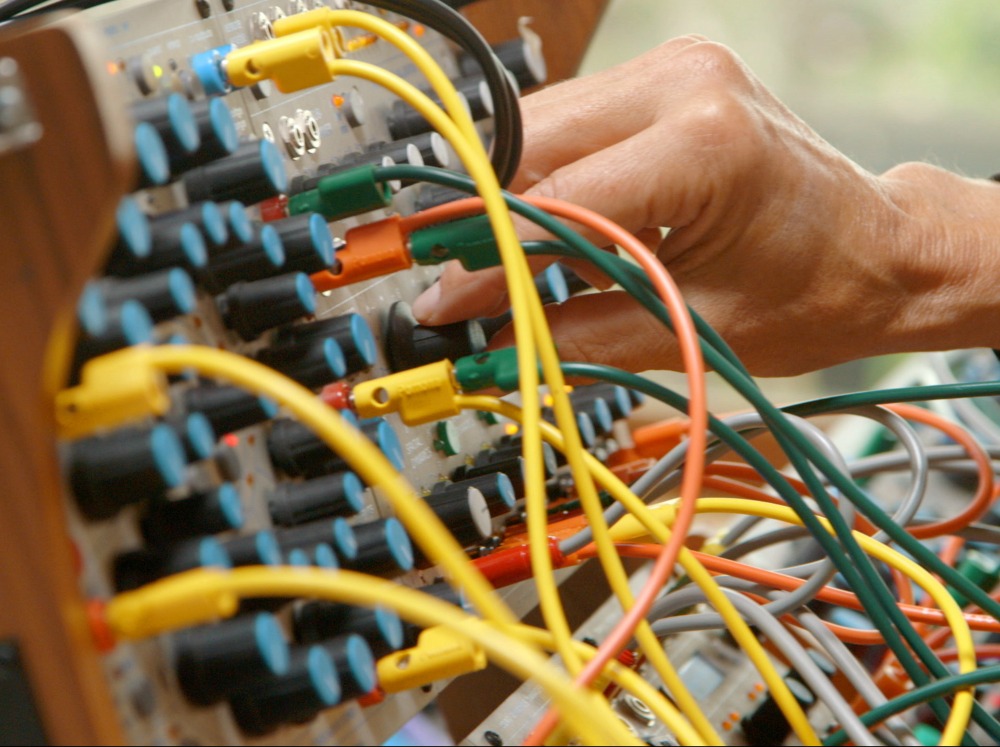

The Ableton lessons were never completed, however, as Ciani shifted focus to restoring her Buchla for a return to live performance. Ciani and Smith know well the Buchla’s attention-demanding nature and the deep-dive tinkering sessions required to master its interface. Ciani invited Smith to dig through her “old recipes” written down in the ‘70s for her Buchla 200; entire sonic environments which Ciani documented on paper to be programmed into the machine’s system.

Ciani composed without the aid of internal memory until the Buchla 200e came along in the 2000s, a modern reboot of her old machine which allows settings to be stored between sessions. “I had so many techniques from working without a memory and had to get rid of all of those. Suddenly [when collaborating with Smith] I had a memory, and it required me to develop new techniques, but how you do it? [With] a memory you have a sort of starting point. You can get a situation in the instrument where you can improvise from a point and then change to another – but the process is really that the memory is giving you a starting point.”

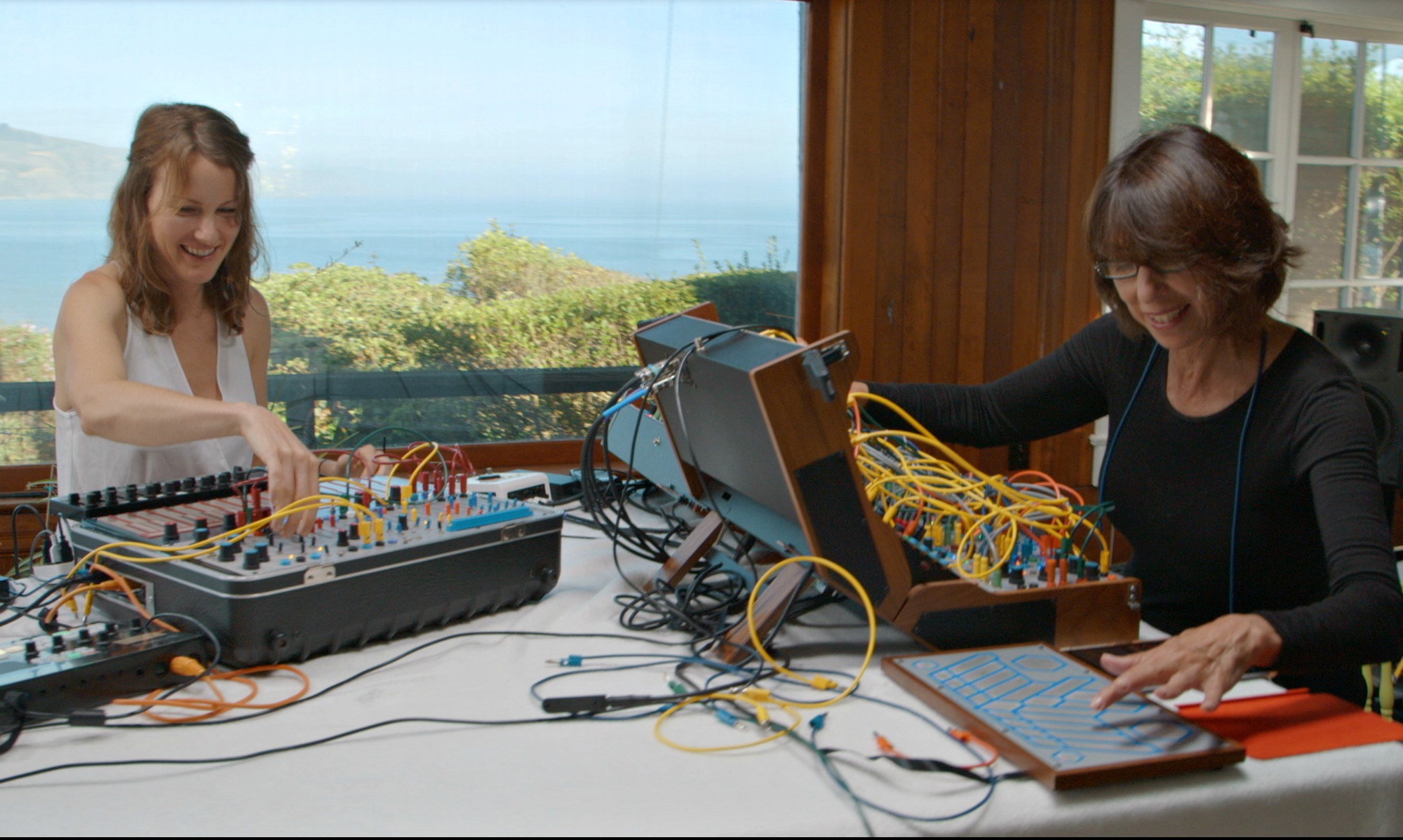

Their stories of the Buchla run parallel and heavily inform the techniques behind Sunergy. Both musicians speak of the synth, its sound and features, as though they were tangible materials; Ciani suggests they were practicing an organic type of composition, piling sounds together as though they were mixing ingredients. They decided to tether their Buchlas together, tangling up each other’s processes, as a starting point for the record. “The synths were side-by-side and we were actually connected by an umbilical cord,” says Ciani. “We were locked rhythmically and could let the energy of the propulsion of the sequencing propel us, and from there we would interact and improvise.”

Bound together in circuitry and positioned over the Pacific Ocean, their human movements were routed through the gridded interface of the Buchla synths to create a romantic vision of the oceanic setting of Bolinas, unfolding as a landscape of undulating waves and structural indentures. Electronic music has historically often been read as “cold” or “inhuman”, but Sunergy is the opposite: curious and sentimental, tying the adaptation of memories and personal experiences with the gear itself and their own deep connections with nature.

“I live in a place where the sun comes up every morning right in my eyes. I’d get up every morning and wait for the sun’s grace,” says Ciani. “I would go to the piano and I’d try to write the sunrise. At a certain point I realised that it was not a piano piece, it was an electronic piece, because [there is a] sustained and connective energy in electronic music that’s hard to get in a percussion instrument like piano.” She admits that she had never intended to work with anyone else on such a personal composition. “I didn’t want to share my sunrise piece, but we did it. We made a piece about the sun and its energy and optimism.”

This deeply personal, real world take on electronic music highlights the evolution of Ciani’s work. In 1980, she assembled the sound effects for Bally’s popular Xenon pinball machine. It wasn’t the first time Ciani had worked to spec – she had formed her own company in 1974 and composed themes and scores for Coca Cola, Atari, AT&T and other corporate brands. With Xenon, however, she was able to experiment a little more. “The person playing the pinball machine would get the sensation that they were the ones generating the sound—it was all triggered by things that you actually did. When you hit the flippers one thing happened, when you hit the bumper one thing happened, so it was all interactive.”

Ciani even used her own voice in the game. The sultry “ooohs” and “aaahs” that gasp when the ball lands a hit made her the first human female voice ever heard in a game. Since then, her fusion of technology and humanity has all been leading towards Sunergy – from the frothy grandeur of her 1982 debut Seven Waves to the Sakamoto-esque Pianissimo trilogy. This time around, there was almost too much to say with music alone, and the duo tapped documentary filmmaker Sean Hellfritsch to capture the recording sessions, spiking the footage with images of the Bolinas seascape Smith and Ciani would watch while they composed and improvised.

For Smith, visuals are an inseparable part of the creative process, and the documentary was a natural extension of the album. “There’s a lot of overwhelming beauty that you can’t quite put to words,” she offers. “My experience seeing these images along with the music burst my heart with how much it communicates what I feel when I look at the coast of Bolinas.”

“The idea for the energy of a wave is that it builds, it crashes, climaxes and then recedes,” adds Ciani. “That energy system is really what I fed off of for the album. The mystical safety of the sea.”

Watch next: Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith brings her modular orchestra to life